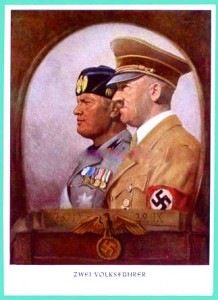

“Every grown-up German is a warrior at heart. In his childhood he plays soldiers, in his old age he relives his battles. They have developed the theory of war [to a fine art], like a game of chess…War is also a dance. The war dance had begun, they say. A minuet. Accompanied by a twenty-five-shot guitar.”

Opening with a brief preface, purportedly written in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, and in Barcelona between 1973 and 1974, the novel’s author describes himself as a “copyist,” asserting that he is trying to make sense of daily notes found in a soldier’s old green canvas rucksack containing “dog-eared exercise books, leaflets, bits of cardboard, scraps of paper covered with an untidy scrawl.” Jakob Bergant-Berk, the soldier who penned these notes during Slovenia’s World War II battles against the Germans and Italians has also included “several selected sayings, quotations, maxims, [which he] entered in the notes, sometimes for no apparent reason, and sometimes as a integral part of them,” and the author/copyist apologizes for being unable to “include in this book even a quarter of the accumulated hodgepodge.” The notes, he says, were obviously made at different times and later bound together, and include sense impressions which show the soldier to have had a highly developed aesthetic sense, even amidst the traumas of war. “The night we call cherry blossom night. A tree – stars like the petals of the white blossom, shooting stars. Over Suha Krajina. A minuet.”

Opening with a brief preface, purportedly written in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, and in Barcelona between 1973 and 1974, the novel’s author describes himself as a “copyist,” asserting that he is trying to make sense of daily notes found in a soldier’s old green canvas rucksack containing “dog-eared exercise books, leaflets, bits of cardboard, scraps of paper covered with an untidy scrawl.” Jakob Bergant-Berk, the soldier who penned these notes during Slovenia’s World War II battles against the Germans and Italians has also included “several selected sayings, quotations, maxims, [which he] entered in the notes, sometimes for no apparent reason, and sometimes as a integral part of them,” and the author/copyist apologizes for being unable to “include in this book even a quarter of the accumulated hodgepodge.” The notes, he says, were obviously made at different times and later bound together, and include sense impressions which show the soldier to have had a highly developed aesthetic sense, even amidst the traumas of war. “The night we call cherry blossom night. A tree – stars like the petals of the white blossom, shooting stars. Over Suha Krajina. A minuet.”

Through all these notes, however, runs one thread which the author/copyist intends to respect: “The soldier’s chief aim was continuity; to engage the reader’s interest was his least concern.”

The novel itself evolves from this introduction, and battle scenes from 1943 alternate with scenes which take place in Barcelona in 1973, sometimes shifting time and place without transitions. It becomes clear that the soldier and the man in Barcelona are the same person, and it is in Barcelona, on vacation many years later, that this man, Berk, meets a former German soldier, Joseph Bitter. In a series of local bars and tourist destinations, they discuss the war, its objectives, and its Machiavellian strategies, a technique which allows the author to expand on some of the many themes to which Berk, the soldier, has referred, however briefly, in his notes. Images of war as a dance of death – a macabre minuet – accompanied by the “twenty-five shot guitar,” mentioned in the opening quotation, are matched with the ironic rat-a-tat-tat of Barcelona flamenco dancers, accompanied by the throbbing of Spanish guitars in the background as the two men talk. The contrast between the seeming peacefulness of nature and what is happening on the front finds its parallel, thirty years later, in the peaceful discussions the author has with Joseph Bitter. During the war, Berk had found that “every battle is an almighty muddle; hardly anyone can get a decent view of the action,” but now, many years later, he and Joseph Bitter both have an opportunity to look at the action from afar.

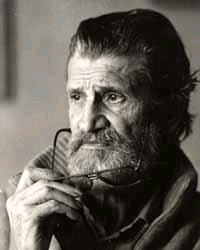

Author Vitomil Zupan (1914 – 1987), widely praised as Sovenia’s premier author of the last half of the twentieth century, is clearly using his own life as a model for much of this action. A member of the Liberation Front of the Slovenian people during the Axis occupation, he was later captured by the Italian authorities, put into a concentration camp, from which he escaped to join the partisans, and participated in battles against the Germans. Always interested in philosophy, something the reader of this novel discovers early, he imbues Berk with some of his own preoccupations regarding the nature of warfare and why men fight, from the cavemen to the Crusaders, the Conquistadores, Hitler, Admiral Nelson, the Greeks of the Iliad, and Alexander the Great, and in wars ranging from Europe to the Americas, India, and Africa.

Throughout this war’s action in Slovenia, Bergant-Berk shows us, there is always a battle between the individual and the war machine. “You’re an individualist, Berk, and people like you contaminate the whole environment with their individualism and liberal ideas…Can’t you be like the rest of us? Must you always be a loner?…I advise you not to make yourself out to be a bigger idiot than you really are.” Berk himself wonders “Where does someone fit in, if he’s against the occupiers, against the Quislings, isn’t a Christian, has no special liking for the English or the Americans or the Russians or for prewar Yugoslavia or the monarchy – and not for one-party leadership either?”

Once the terrible battles start, they never seem to end, and it sometimes seems as if Berk is recreating every possible movement and battle in Slovenia during the entire war. Ironically, however, the actual time span is only one month – from October to November, 1943. Men, some of them friends, are shot, maimed, or killed. They fight lice and crabs, they get infections and frostbite in the mountains, and nothing ever seems to end. As Berk notes, “It is hard to say whether it is all happening simultaneously or in sequence…or whether some impression was valid or not…Surrounded by visions and illusions, each man reacts instinctively and adapts to his circumstances. In the mass of jumbled shapes and sounds, there is a sudden flurry as he springs into action.” At one point, Berk muses, “Perhaps man is a mere bubble in time’s froth, doomed to disappear without trace; but no one can prove this. Who can deny that within me, there still live on many men who have died, perished, vanished into thin air?…Vili the musician: how often he comes back to mind! He still lives and demands that I remember him.”

Powerful and thought-provoking in its philosophical examination of warfare on a grand scale, Minuet for Guitar, written in 1975 and newly translated and published by Dalkey Archive Press, gives new insights into the plight of a man caught in the spiral of violence over which he has little control, a man who nevertheless volunteered to help free his country from occupation. It is Berk’s friend Anton who sums it all up: “When, during a war, you have the feeling that there is no distinction between eternity and a moment of time, between a drop of water and the ocean, between a whirlwind and a sigh, that large and small no longer exist, when there is an atmosphere of spontaneous general expectation, then the day is coming when we can say that the war is over…Later, the bitter reality brings us back to earth, for in the end, absolutely nothing has changed.” A stunning and memorable novel which deserves much wider readership.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on his Wiki page: http://en.wikipedia.org

The map of Slovenia and surrounding countries is from http://geology.com

The photo of Mussolini and Hitler appears on http://usmbooks.com

Ljubljana Castle, overlooking the capital city, dates from 1112 to 1125 and is the sight Berk most wishes for during much of the warfare. http://www.slovenia.info