“Every time he saw the bomboys set off with a canoe full of slaves, he thought of his father standing on the shores of the Cape Coast Castle, ready to receive them. On this shore, watching the canoe push off, Quey brimmed with the same shame that accompanied each slave departure. What had his father felt on his shore [when they had arrived]?….Was it the same mix of fear and shame and loathing that Quey felt for his own flesh, his mutinous desire?” – thoughts of Quey, son of Effia Otcher and James Collins, British governor of the colony.

In a novel which is both emotionally intimate and broad in its scope and thematic impact, this debut novel by twenty-six-year-old Ya’a Gyasi, formerly of Ghana, truly deserves its description as an “epic.” The young recipient of NPR’s Debut Novel of the Year last year for Homegoing, the much lauded Gyasi was today awarded the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize for Best Debut Novel of 2016, for this same novel. She had come to the U.S. from Ghana at a young age and grew up here, but she returned to Ghana for the first time during her sophomore year in college primarily to do research for a novel. Instead, she found the experience much more personal and affecting than she expected as she gained new insights into who she is and where she came from, insights which ultimately changed her life. As she was touring the Cape Coast Castle in which, long ago British governors and the local women they married lived comfortable lives, Gyasi confesses that she was stunned by the contrast between life in those “upstairs” rooms and in the rooms of the dungeon beneath the castle. There twenty or more women per cell, about to be shipped out as slaves, spent their last painful days in Africa before going through the Door of No Return and entering the cargo holds of the ships taking them to America to be sold.

In a novel which is both emotionally intimate and broad in its scope and thematic impact, this debut novel by twenty-six-year-old Ya’a Gyasi, formerly of Ghana, truly deserves its description as an “epic.” The young recipient of NPR’s Debut Novel of the Year last year for Homegoing, the much lauded Gyasi was today awarded the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize for Best Debut Novel of 2016, for this same novel. She had come to the U.S. from Ghana at a young age and grew up here, but she returned to Ghana for the first time during her sophomore year in college primarily to do research for a novel. Instead, she found the experience much more personal and affecting than she expected as she gained new insights into who she is and where she came from, insights which ultimately changed her life. As she was touring the Cape Coast Castle in which, long ago British governors and the local women they married lived comfortable lives, Gyasi confesses that she was stunned by the contrast between life in those “upstairs” rooms and in the rooms of the dungeon beneath the castle. There twenty or more women per cell, about to be shipped out as slaves, spent their last painful days in Africa before going through the Door of No Return and entering the cargo holds of the ships taking them to America to be sold.

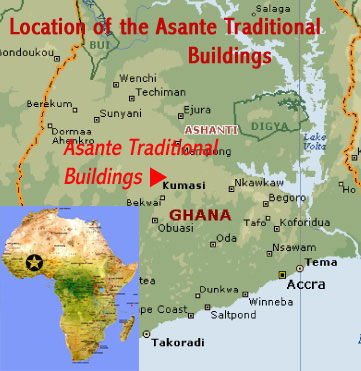

Opening her novel in the mid-1700s, Gyasi recreates the tumult of what is now Ghana as the Fante tribes from the coastal area and the Asante (Ashanti) tribes from inland constantly battle each other for power, a task complicated by the fact that the British have occupied the coastal areas so that they can manage the lucrative shipping of slaves to America. Anyone captured by an enemy soldier, of either tribe, is destined to be sold to the British for export, and when the inland Asante also steal large amounts of guns and ammunition from the British and escape inland, the whole social fabric changes. The opening chapters, which establish this background, also introduce the first of eight generations reflected in the lives of two families: the descendants of the beautiful Effia, born in Fanteland, and the descendants of Esi, her half-sister, an Asante royal whom she does not know. While Effia strikes the fancy of James Collins, governor of the colony, who marries her and brings her to the beautiful Cape Coast Castle where he lives and works, Esi becomes just another anonymous voice that Effia hears emerging from the floors below her – in the dungeons. Esi is eventually shipped to America, living out the sad history of slavery and its aftermath, while Effia and her descendants remain in Ghana.

Opening her novel in the mid-1700s, Gyasi recreates the tumult of what is now Ghana as the Fante tribes from the coastal area and the Asante (Ashanti) tribes from inland constantly battle each other for power, a task complicated by the fact that the British have occupied the coastal areas so that they can manage the lucrative shipping of slaves to America. Anyone captured by an enemy soldier, of either tribe, is destined to be sold to the British for export, and when the inland Asante also steal large amounts of guns and ammunition from the British and escape inland, the whole social fabric changes. The opening chapters, which establish this background, also introduce the first of eight generations reflected in the lives of two families: the descendants of the beautiful Effia, born in Fanteland, and the descendants of Esi, her half-sister, an Asante royal whom she does not know. While Effia strikes the fancy of James Collins, governor of the colony, who marries her and brings her to the beautiful Cape Coast Castle where he lives and works, Esi becomes just another anonymous voice that Effia hears emerging from the floors below her – in the dungeons. Esi is eventually shipped to America, living out the sad history of slavery and its aftermath, while Effia and her descendants remain in Ghana.

The Cape Coast Castle, on the southern coast of Ghana, is located here just southwest of Saltpond. The Fante tribes lives along this coast. Click to enlarge.

As the generations tell their stories, the full talent of this author becomes clear. Each section, named for the main character of the section, alternates with a later chapter from the same time period and a new character from the other, parallel family. Gyasi shows her talents for characterization by establishing qualities for these characters which allow the reader to understand and often identify with them. Quey, son of Effia and James Collins, is a man who could pass for white and who has been educated in England and then returned to Ghana where he no longer fits in. His other-family counterpart is Ness, daughter of Esi, who leads a hard life picking cotton in America and who eventually marries Sam and has a baby, for whom they sacrifice all. The images from this section permeate much of the overall action of the novel, and the dedication of the parents to their child cannot be overestimated. Gyasi makes them come alive, and though they are symbols of slavery and of the harsh world imposed by the powerful upon the weak, they feel more like real people than symbols, however powerful the symbolism may be.

Characters’ goals change over the generations. One person, James, son of Quey, eventually decides to follow love and abandon the obligations imposed upon him as the son of Fante royalty to become a farmer in a new village. Kojo, Ness’s son in America, is a freeman living with a sympathetic family whose house is a stop on the Underground Railway. His son H, though also “free,” illustrates the problems of someone who has to sell himself to work in the mines for ten years in order to support a family, not much different from those who are owned by “masters.” The Civil War has not made much positive difference in their lives, at this point, and those who have to work the mines are vulnerable to severe health problems. The development of unions and the use of strikes as a weapon lead to a terrible form of undeclared civil war, with the mine owners using weapons to maintain their control.

When some of the characters end up in New York and Harlem in the twentieth century, trying to support themselves as housekeepers, singers in jazz clubs, or drug dealers, the events make direct connections with contemporary readers. Some characters begin to think of returning to Africa, their roots, not because they have any memories of Africa, but because they believe it must be more conducive to a “real” life than what they have found in the US. As the time period becomes more up to date, the last two generations merge, as each of the final characters represents one of the two families which have been traced for so many generations. Each must decide whether to revisit the past, mostly unknown, or stay put and face the future there.

Throughout, Gyasi incorporates elements common to great, majestic novels in this highly compressed epic of black lives and struggles. The continuing symbol of a black stone necklace belonging to the first generations of the novel and continuing to the present adds a kind of elegance and sense of continuity which grounds the novel for eight generations. Folk stories, legends which evolve about some characters, the fears created by dreams and vague family memories, and the persistent drive to be successful while lacking a true understanding of themselves and their past make this novel “speak” to a modern audience, regardless of race or color. A novel so broad, universal, and effective makes one wonder what Ya’a Gyasi can possibly do as an encore after this novel.

Note: This CNN video features President Obama visiting the Cape Coast Castle with Anderson Cooper:

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from https://www.penguin.co.uk/

The map of Ghana, showing the Asante and Fante areas appears on http://www.africanworldheritagesites.org/

The wonderful photo of Cape Coast Castle is featured on https://nicoleinghana.wordpress.com/

The Door of No Return led to the waterfront and the British ships taking captives to America. http://africancelebs.com/

The CNN video of Anderson Cooper and President Obama is on Youtube.