“Why was he always in this situation, waiting for something to happen? This must be what ‘living’ was all about. While he was working at Tokyo Ad, it had actually been more a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where…[no one ever] got their hands dirty… Most likely, those colleagues would think it oddly contradictory now to discover Hanio, who had determined to die, sipping brandy and looking forward to the future.”

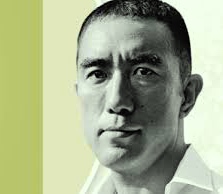

Life and death dominate much of the writing of prolific Japanese author Yukio Mishima (1925 – 1970), the author of more than thirty novels, approximately fifty plays, twenty-five books of short stories, and six films, all of them written before he turned forty-five. Yet though he was nominated for a Nobel Prize in 1968, before his famous Sea of Fertility tetralogy of historical novels was even finished, he is far better remembered, at least in western countries, for the nature of his death, rather than for the vibrant novels he wrote during his life. The son of a conservative family, Yukio Mishima was always dedicated to Japan’s ancient samurai traditions, and his early death was by ritual suicide when he and three friends single-handedly tried and failed to bring about a coup at the Japan Self-Defense Headquarters in Tokyo on November 25, 1970. They had hoped to restore the emperor to the power which he had lost twenty-five years earlier when Japan was forced to surrender at the end of World War II. Details of Mishima’s ritual suicide, including his self-disembowelment and his botched beheading by his assistants, remain to this day the primary images of Mishima for many westerners who know his name but are unfamiliar with his writing.

Life and death dominate much of the writing of prolific Japanese author Yukio Mishima (1925 – 1970), the author of more than thirty novels, approximately fifty plays, twenty-five books of short stories, and six films, all of them written before he turned forty-five. Yet though he was nominated for a Nobel Prize in 1968, before his famous Sea of Fertility tetralogy of historical novels was even finished, he is far better remembered, at least in western countries, for the nature of his death, rather than for the vibrant novels he wrote during his life. The son of a conservative family, Yukio Mishima was always dedicated to Japan’s ancient samurai traditions, and his early death was by ritual suicide when he and three friends single-handedly tried and failed to bring about a coup at the Japan Self-Defense Headquarters in Tokyo on November 25, 1970. They had hoped to restore the emperor to the power which he had lost twenty-five years earlier when Japan was forced to surrender at the end of World War II. Details of Mishima’s ritual suicide, including his self-disembowelment and his botched beheading by his assistants, remain to this day the primary images of Mishima for many westerners who know his name but are unfamiliar with his writing.

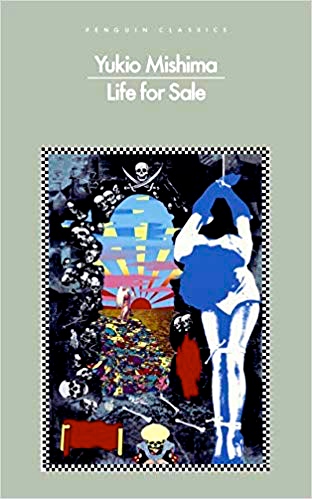

For Mishima, Japan’s past plays a major role in his best work, widely considered to be his Sea of Fertility tetralogy (Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn, and The Decay of the Angel), published in Japan between 1965 and 1970. Here he follows one man, a young law student in his twenties in 1912 until his late years in the 1970s, when he is a retired judge. His best friend, during this time, appears in successive reincarnations in the three later novels, which provide a vibrant picture of Japan, its people, and its culture from the beginning of World War I through World War II and its aftermath. Mishima, however, did not limit himself to the kind of literary fiction which these novels embody. His novel Star (1961) is the romantic story of a film star, a subject Mishima knew well from his own experience in film and stage. Life for Sale, written in 1968, and just published in the US for the first time, is considered “pulp fiction,” though it is so well written that it feels less like pulp and more like a dark satire about a man without a real purpose, perhaps displaying some of the issues with which Mishima himself had to deal and which led to his own premature death.

For Mishima, Japan’s past plays a major role in his best work, widely considered to be his Sea of Fertility tetralogy (Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn, and The Decay of the Angel), published in Japan between 1965 and 1970. Here he follows one man, a young law student in his twenties in 1912 until his late years in the 1970s, when he is a retired judge. His best friend, during this time, appears in successive reincarnations in the three later novels, which provide a vibrant picture of Japan, its people, and its culture from the beginning of World War I through World War II and its aftermath. Mishima, however, did not limit himself to the kind of literary fiction which these novels embody. His novel Star (1961) is the romantic story of a film star, a subject Mishima knew well from his own experience in film and stage. Life for Sale, written in 1968, and just published in the US for the first time, is considered “pulp fiction,” though it is so well written that it feels less like pulp and more like a dark satire about a man without a real purpose, perhaps displaying some of the issues with which Mishima himself had to deal and which led to his own premature death.

Life for Sale opens with main character Hanio in the hospital recovering from an overdose of a sedative, assumed to be intentional, though “He was not suffering as the result of some romantic breakup…Nor did he have any serious financial problems.” He had been working as a copywriter for an advertising company and had no thoughts of suicide until he dropped a piece of newspaper. When he stooped to pick it up, a cockroach had landed on top of it, and “Suddenly, all the letters he was trying to make out turned into cockroaches…as they made their escape, their disgustingly tiny dark-red backs in full view.” He concludes, grimly, that “the world boils down to nothing more than this.” From that moment on, “death hung over him, snugly, the way snow caps a red postbox after a particularly heavy snowfall.” Since his suicide attempt was a failure, he decides to resign from his job and use his substantial severance pay to do whatever he wants in what remains of his lifetime.

The mobster who is having an affair with an old man’s wife resembles a character from the manga books which the wife enjoys.

Returning to his apartment, he places a note on his front door: “Hanio Yamada – Life for Sale.” What follows is a series of adventures, as five different characters come to his door to hire him to work on projects so dangerous that Hanio could die while working. Since there are five successive “sales,” it is obvious that something unexpected happens each time Hanio is hired, and it is these bizarre twists which make the episodes intriguing. His first customer, a well-dressed man in his seventies, comes to his apartment and describes his “magnificent” wife, now age twenty-three, confessing that she has left him and is now “shacked up” with a mobster, “but not your ordinary, run-of-the mill mobster.” This one resembles a character from the manga stories his wife adores, and he has already “knocked off” a couple of people in turf wars. The old man wants the mobster dead – and his wife, too. The second episode involves a woman who steals a rare library book describing a genus of Japanese beetle which can be ground and used as a powder to hypnotize a victim and make a death look like suicide. She wants to test the effects of this scarab beetle and wants Hanio to be the test case.

A small boy figures in the third story, one which may bring smiles even as it becomes a horror story. Young Kaoru has taken and sold a valuable family sketch by Tsuguharu Fujita to get the money needed to hire Hanio. The boy’s mother, he says, is a vampire, and she is dying now from lack of nourishment. The boy hires Hanio to keep his mother alive. Episode #4 features an ambassador whose wife has an emerald necklace stolen at an official dinner. The necklace contains a secret code, and several officials have died as a result of the enmity between two involved countries. Poisoned carrots play a role, and once again, Hanio escapes. “To say that human life had no meaning was the easy part, [and] Hanio was struck all over again by the huge amount of energy required to live a life filled with so much meaninglessness.” The final story links all the others thematically and answers some of the final questions. A young woman is wrongly convinced that she has a fatal illness, and Hanio finds himself being tracked as he deals with her and eventually, the police.

It is tempting to “see into” some of these episodes to imagine some of the issues which the author himself may have been facing in his own life, but the overall feeling here is one of clever trickery, rather than horror, with Mishima’s literary skill surviving even the accusation that this is “pulp” fiction. His lighter touch here allows him to deal with life and death in a less serious fashion than in his great works, and the excitement he generates makes the book feel satiric and more fun to read, despite its occasional gore.

ALSO reviewed here: FROLIC OF THE BEASTS, SPRING SNOW #1, RUNAWAY HORSES #2 , TEMPLE OF DAWN #3, STAR

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.wallofcelebrities.com/

The red post box is from https://instaphenomenons.me

The mobster who is having an affair with an old man’s wife resembles a character in one of her manga favorites. https://en.wikipedia.org/

Young Kaoru sells a sketch by famed Japanese artist Tsuguharu Fujita to pay for the services of Hanio in helping his mother regain her strength. https://www.allpainter.com/