“She is a dreamer. A raw sienna mother with splashes of crimson. And she spends her red days lying naked on the red soil between two peach trees with blue trunks. She gave birth to the trees so that they could provide her with shade. But there is hardly any shade because the trees do not bear leaves. Only pink blossoms. Born and reborn all year round. Without bearing fruit.”–portrait of a black Madonna by Fr. Frans Claerhout.

Niki, the mother in the painting described above and the main character in this novel, poses often for Father Frans Claerhout, an artist whose expressionistic paintings in bright colors feature native South Africans as the models for religious paintings. Niki, who posed originally because she desperately needed the money and was willing to travel thirty-five kilometers to Fr. Claerhout’s studio, often on foot, is a favorite model, along with her daughter Popi, a five-year-old, light-skinned child with blue eyes and softly waving hair.

Niki, the mother in the painting described above and the main character in this novel, poses often for Father Frans Claerhout, an artist whose expressionistic paintings in bright colors feature native South Africans as the models for religious paintings. Niki, who posed originally because she desperately needed the money and was willing to travel thirty-five kilometers to Fr. Claerhout’s studio, often on foot, is a favorite model, along with her daughter Popi, a five-year-old, light-skinned child with blue eyes and softly waving hair.

Niki’s story – from her teen years to old age – here becomes the story of South Africa during the last half of the 20th century, a novel told from the perspective of a black author, and quite different from the novels of Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer, and J. M. Coetzee, though they cover the same period of history. In sensuous, intensely visual language, author Zakes Mda recreates Niki’s life, showing her day-to-day struggles under the apartheid government of the Afrikaners while also depicting her as Fr. Claerhout sees her in his paintings – as a colorful Madonna figure, the mother of children who will eventually change the world. Without resorting to melodrama or clichés, he portrays Niki as an imperfect, sometimes angry, and often calculating woman determined to hang on to her pride while using the only power she has, her sexual power over the men who would control her.

Excelsior, the township in which Niki lives, has 2470 whites, 23,594 blacks, and 580 colored (mixed race) in 1971, yet every governmental position is held by whites, all major businesses are white-owned, and all power rests in white hands. Through Niki’s story, the reader sees black women regarded as chattel, raising the children of the whites (often at the expense of their own black children), while being paid barely subsistence level wages to do jobs no one else will do. Often mistrusted and humiliated by employers, and regularly harassed and even raped by their bosses, town officials, judges, and even clergymen, they are victimized again and again, yet we see in Niki a woman who never yields to self-pity, maintaining her pride even when she and eighteen other women and the men who have used them are put on trial for violating the Immorality Act, a violation which produced Niki’s daughter Popi.

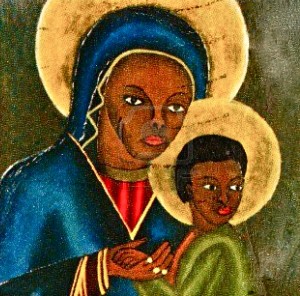

Black Madonna, postage stamp by an unknown artist

The small town in which the action takes place, Excelsior, is a microcosm of the larger country of South Africa. Here the reader becomes acquainted with the townspeople of both races, develops sympathy for some and abhorrence of others, and sees South African life as it affects fully-developed and realistic characters of both races. It is the “colored” people, like Popi, who belong to no culture, who have the most difficult lives – they are too white for the black society in which they try to live, and far too black to be part of white society, even if they wanted to be.

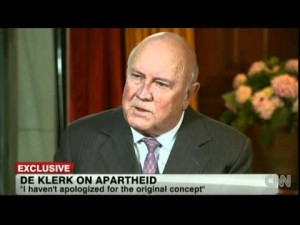

F. W. De Klerk

Not without violence does the political climate eventually change from the conservative Afrikaner belief that it is their God-given right to rule, to the rule of the black African majority. Yet very little of the actual violence is shown in Excelsior. Popi, her brother Viliki, and a group of young people have been part an underground movement that has gained the support of laborers and ordinary black people who believe in the Movement’s idealistic goals, and they have forced the ruling powers to take notice of them. Observers, such as the book’s unnamed narrator, comment that Viliki and Popi have experienced a rebirth from their political involvement, “Born again, not into some charismatic religious faith….[but] into the suaveness of local government politics.” And when both Popi and Viliki both join the governing council of the town, they become “a united front against retrogressive forces in the council chamber. For two years, the voice that came from their mouths was one voice.”

Nelson Mandela

All over South Africa, similar changes were taking place by the early 1990s, with South African President F. W. de Klerk ending apartheid and releasing Nelson Mandela from jail, but these national changes are treated only peripherally. The author keeps the action firmly focused on the changes in the lives of Excelsior’s “little” people, both black and white, as they are affected by the winds of change. And, the author shows, changes – not always good – continue, even after the blacks elect a majority of councilors and a black mayor: “As soon as the [black] revolutionaries had got into power…they had focused on accumulating farms and hotels for themselves. Ardent revolutionaries continued to use the rhetoric of socialism, while in behaviour and outlook they were born-again capitalists.”

With vivid scenes from South African life, both the good and the bad, from the 1970s to the present, author Mda presents a clear-eyed vision of South Africa’s transition from a restrictive, white-ruled government to a democratically elected government with room for both races. The black people here are real, not idealized, people with real hopes, dreams, and strategies for survival, and they evoke enormous sympathy from the reader, especially as their personal limitations and faults become clear. Though Mda has no sympathy for the abuses inflicted by the Afrikaners who were in power for so long, he reveals a broad vision of a future that includes both races working together. Concentrating less on national violence and battles for survival, and more on the individual, racial conflicts of people in Excelsior, many of whom the reader has come to like and respect, he presents an exciting story of complex issues in a clear, straightforward narrative which throbs with life and offers both hope and warnings for the future.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.thenewage.co.za

The portrait of a black Madonna is by an unknown Haitian artist and appears on a British postage stamp: http://www.stamp-photos.com

F. W. De Klerk, former President of South Africa, under apartheid, may be seen here:

http://innerstandingisness.com

The Nelson Mandela photo by Themba Hadebe is from http://article.wn.com Nelson Mandela and F. W. De Klerk were the joint winners in 1993 of the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in dismantling apartheid in South Africa.

Excelsior is located in the Free State in South Africa, at the junction of the co-ordinates seen here – just above the “L” in Lesotho. Map from http://nona.net