“Be it thus that we, emulating the purity of the League of the Divine Wind, hazard ourselves for the task of purging away all evil deities and perverse spirits. Be it thus that we, forging deep friendship among ourselves, aid one another as comrades in responding to the perils that confront the nation. Be it thus that we, never seeking power and giving no thought to personal advancement, go forth to certain death to become the foundation stones for the Restoration.”—oath of the League of the Divine Wind.

Yukio Mishima’s Sea of Fertility tetralogy, of which this novel is the second in the series, incorporates four novels set in four different time periods, illustrating Mishima’s extremely conservative attitudes toward the changes in Japan from 1912 to 1970. Born in 1925, Mishima had, throughout his life, mourned the loss of samurai ideals, including reverence for the Emperor. He lashed out against the westernization of Japan which he believed began with the Meiji Dynasty in the nineteenth century and continued to escalate throughout the twentieth century, and he was devastated by the defeat of Japan in World War II, the demeaning of the Emperor, and the Occupation by Allied troops. For the next twenty-five years after the war, Mishima practiced samurai ideals, until in 1970, having completed the fourth novel of this series, he and a group of five private militia men, who were also samurai, led a futile assault on the headquarters of the Japanese armed forces in an effort to stage a coup, then committed seppuku, the ritual suicide by disembowelment favored by the samurai.

Yukio Mishima’s Sea of Fertility tetralogy, of which this novel is the second in the series, incorporates four novels set in four different time periods, illustrating Mishima’s extremely conservative attitudes toward the changes in Japan from 1912 to 1970. Born in 1925, Mishima had, throughout his life, mourned the loss of samurai ideals, including reverence for the Emperor. He lashed out against the westernization of Japan which he believed began with the Meiji Dynasty in the nineteenth century and continued to escalate throughout the twentieth century, and he was devastated by the defeat of Japan in World War II, the demeaning of the Emperor, and the Occupation by Allied troops. For the next twenty-five years after the war, Mishima practiced samurai ideals, until in 1970, having completed the fourth novel of this series, he and a group of five private militia men, who were also samurai, led a futile assault on the headquarters of the Japanese armed forces in an effort to stage a coup, then committed seppuku, the ritual suicide by disembowelment favored by the samurai.

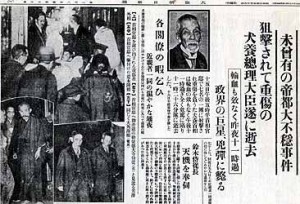

The first novel in the series, Spring Snow (1968), takes place between 1912 and 1914 and introduces young characters of both sexes who live traditional upper class lives. Runaway Horses (1969), continues the story in 1932 – 1933, a time in which Japan is beset with enormous internal problems, all of which are illustrated here: “The shameful state of foreign affairs, the government’s economic program which was doing nothing to relieve rural poverty, the corruption of politicians, the rise of communism, and then the political parties’ halving the number of Army divisions and championing the cause of arms cutbacks.” Many incidents of political violence have taken place, including the assassination of the Finance Minister, and on May 15, 1932, the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai himself, by eleven Navy officers.

The Assassination of Prime Minister Inukai on May 15, 1932,

As the novel opens, Shigekuni Honda, a main character in Spring Snow, now a judge in the Osaka Court of Appeals, has reached the age of thirty-eight, a man leading a quiet life of reason who believes that his youth ended with the death of his friend Kiyoaki Matsugae, eighteen years earlier. When he is asked to represent his Chief Justice at a kendo exhibition in Nara, some distance away, he accepts. The star of the exhibition is young Isao Iinuma, the nineteen-year-old son of Kiyoaki’s tutor during their childhood, a man who now operates a kendo academy, the Academy of Patriotism. Later, after climbing Mount Miwa to visit the Iwakura Shrine, Honda performs a purification ritual in a waterfall and sees, once again, young Isao. This time he is stunned to notice a pattern of three moles under Isao’s arm. His friend Kiyoaki had exactly the same pattern of moles, and had insisted on his deathbed that “I will see you again.” Honda, who has always grounded his life in reason, now believes that Isao is the confident samurai reincarnation of Kiyoaki, who was a sensitive man of passion and emotion a generation earlier.

At the Saigusa Festival of Wild Lilies, Isao gives Honda a copy of a small book which is a prized possession: “The League of the Divine Wind,” by Yamao Tsunenori, which rails against making Japan a republic and insists that all foreign influences be eliminated. (The Japanese word for “Divine Wind” is “kamikaze.”) Long passages from this fictional creation,which go back to the early parts of the Meiji dynasty, set the scene for the action to follow. Though Honda, in his note when he returns the book, cautions Isao against “confusing this tale of dreamlike beauty of another time with the circumstances of present day reality,” and advises him to “look at history from a broad and balanced view,” Isao, of course, wants immediate action against the abuses he has seen during his short life and which he regards as contrary to the samurai code. He establishes a group of other young men who plan executions of those violating the integrity of this code.

The Imperial Palace

Rich descriptions of nature, including a section in which a white camellia is personified, accompany the developing action, and some nature scenes of obvious symbolism add to the dilemma faced by Honda as he remembers dreams which Kiyoaki has recorded in his diary and left for Honda as a legacy. Complications which connect the period of the 1930s with the 1912 – 1914 period of the previous novel add to the depth of the insights here. And as Isao begins to plan for what is the climax of this novel, full of surprises for the reader, one can see the author preparing the way for new understandings.

The biggest surprise for me here was that Mishima was able to give a voice to points of view that would otherwise have been totally alien to me. By explaining the samurai code within the context of Japanese history and culture, and using characters of different beliefs whom I liked and respected, he was able to make me understand much of what lay behind the suicide he himself committed shortly after completion of the tetralogy. Perhaps he thought as Isao does, after touching his lips with the petals of a lily, “Here is the source of my purity, the warrant for my purity…When the time comes for me to turn my sword against myself, lilies will surely rise from the morning dew and open their petals to the rising sun. Their scent will purify the stench of my blood. So be it! How can I have any more doubts.”

Ichigaya Prison

Though the book is sometimes propagandistic and deals almost exclusively with men, Mishima is a novelist who is in complete control of his subject matter, and his thematic transition between the 1912 and the 1932 periods is flawless. The Sea of Fertility, which gets its title from a place on the moon, has always been regarded as his masterpiece, and readers interested in Japan will not want to miss this novel.

Also by Mishima: THE FROLIC OF THE BEASTS, SPRING SNOW #1, RUNAWAY HORSES #2,

THE TEMPLE OF DAWN #3 LIFE FOR SALE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo was taken on the balcony from which Mishima was exhorting the army to join him in the coup he had undertaken in 1970. Minutes afterward, Mishima committed seppuku. http://madmonarchist.blogspot.com

The newspaper report of the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai on May 15, 1932, is from http://en.wikipedia.org

The Saigusa Festival of Lilies is shown on http://photojapan.karigrohn.com.

The Imperial Palace appears on http://www.aliceinwonderlands.com

The Ichigaya Prison, built in 1904, is seen on http://old.japanfocus.org.