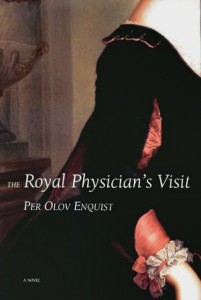

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Independent Foreign Fiction Award and the Nelly Sachs Prize in 2003, when it was published in Sweden. In 2010, Per Olov Enquist was WINNER of the Swedish Academy Nordic Prize, the “little Nobel.”

“They see me as a father who must not be disturbed. They play at my feet and they hear the scratching of my pen, and they whisper.” –Dr. Johann Friederiche Struensee, commenting on the behavior of eighteen-year-old King Christian, his page, and his schnauzer dog, while the doctor works.

Palace intrigue of the highest order, conducted by courtiers and officials who will do anything to achieve their goals, makes this novel by Swedish author Per Olov Enquist both stimulating and thoroughly engrossing, and few who read it will fail to notice the similarities of the “normal” behavior one sees between these courtiers in their time and place and those “aides” or sycophants who surround other leaders of other countries in other times. The Danish court from 1768 – 1772 pulses with life as powerful personalities collide in their rush to fill the power vacuum resulting from the weakness of King Christian VII, a sensitive, half-mad 17-year-old boy, who married the innocent and unsuspecting Princess Caroline Mathilde, the 15-year-old sister of Britain’s King George III, just two years before the novel opens.

Palace intrigue of the highest order, conducted by courtiers and officials who will do anything to achieve their goals, makes this novel by Swedish author Per Olov Enquist both stimulating and thoroughly engrossing, and few who read it will fail to notice the similarities of the “normal” behavior one sees between these courtiers in their time and place and those “aides” or sycophants who surround other leaders of other countries in other times. The Danish court from 1768 – 1772 pulses with life as powerful personalities collide in their rush to fill the power vacuum resulting from the weakness of King Christian VII, a sensitive, half-mad 17-year-old boy, who married the innocent and unsuspecting Princess Caroline Mathilde, the 15-year-old sister of Britain’s King George III, just two years before the novel opens.

These are years of great intellectual ferment as the powerful new ideas of the Enlightenment, with their value on the individual and freedom, begin to threaten the feudal basis of the old, autocratic monarchies of Europe, and more frightening to the courtiers, their own power within their countries. The American Revolution against England is only a few years away, and the French Revolution by its own people will happen only a few years after that. Enquist brilliantly recreates the psychology of the sickly king, a puppet who desperately wants to please the courtiers and officials and is tormented when he does not, a bright but “ravaged child,” who from his earliest years was regularly flogged, ridiculed, beaten for casual conversations, forcibly separated from everyone with whom he developed attachments, shamed, and driven mad by his own courtiers.

When the young king becomes interested in the enlightened ideas of Voltaire and Diderot and is celebrated by these philosophers on a trip around the continent, his nervous and threatened court decides he needs a physician to disabuse him of these “follies.” What they never expect is that the physician they engage, Johann Friedrich Struensee from Germany, will quickly establish a strong and genuinely caring relationship with Christian, share his enlightened ideas, and eventually become the de facto king and lover of the young queen Caroline Mathilde.

When the young king becomes interested in the enlightened ideas of Voltaire and Diderot and is celebrated by these philosophers on a trip around the continent, his nervous and threatened court decides he needs a physician to disabuse him of these “follies.” What they never expect is that the physician they engage, Johann Friedrich Struensee from Germany, will quickly establish a strong and genuinely caring relationship with Christian, share his enlightened ideas, and eventually become the de facto king and lover of the young queen Caroline Mathilde.

Bursting with dramatic scenes of Machiavellian court intrigue and the courtiers’ well-justified fear of the Enlightenment, the novel also includes powerfully moving descriptions of the deliberate psychological abuse of Christian VII. These scenes contrast with other instances of tenderness, passion, love, and genuine sadness, as the author turns the royal personages, courtiers, their allies, and Dr. Struensee into real people. Though the reader knows from the opening pages what the outcome of the court struggles will be, Enquist manages to endow this turmoil with an immediacy and tension which totally engage the reader, clearly illustrating the rage for power and the lengths some will go to gain and keep it. Few who read this novel will fail to recognize the common traits shown by powerful but desperate people, regardless of country, era, or the nature of the issues they are facing.

By focusing on the court, rather than on the populace itself, for his point of view, the author brings the Enlightenment and the revolutions it inspires throughout Europe to new life from a new perspective, and in creating this novel based on history, he brings to life both the sad and abused child-king Christian, and Struensee, the enlightened but politically naïve mentor forced to pay the ultimate price.

By focusing on the court, rather than on the populace itself, for his point of view, the author brings the Enlightenment and the revolutions it inspires throughout Europe to new life from a new perspective, and in creating this novel based on history, he brings to life both the sad and abused child-king Christian, and Struensee, the enlightened but politically naïve mentor forced to pay the ultimate price.

Note: Readers who become interested in this story will find in Wikipedia a wealth of additional information bringing the story of Christian VII, and especially that of the now nearly unknown Caroline Mathilde to its dramatic conclusion a few years after this novel ends.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Anders Roth/SR Bild is from http://sverigesradio.se

The portrait by Dr. Johann Struensee appears on http://www.skoletjenesten.dk/

Caroline Mathilde, the young Queen, is shown here: http://en.wikipedia.org

King Christian VII, with his crown resting on the table beside him, is seen on http://en.wikipedia.org

This book has been made into an opera, garnering rave reviews in Copenhagen and elsewhere. Here is the trailer: