Note: In 1973 Patrick White was named WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature. This novel was the WINNER of the 1957 Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s highest literary award, in its inaugural year.

“Every man has a genius, though it is not always discoverable, least of all when choked by the trivialities of daily existence…[If you attempt to discover it,] you will be burnt up most likely, you will have the flesh torn from your bones, you will be tortured probably in many horrible and primitive ways, but you will realize that genius of which you sometimes suspect you are possessed.” Johan Ulrich Voss, before the expedition.

Australian Patrick White’s genius for story-telling is on full display in this big,old-fashioned saga filled with intriguing characters exploring the difficult terrain of their inner lives. For a number of characters, all male, that personal inner journey is also part of a daring adventure they make into the interior of Australia in the mid-nineteenth century, an area previously unexplored by the white people who have recently discovered this continent. The female characters in Sydney during this same period have a far more difficult time exploring their inner natures, even in the unlikely event that they might be interested in doing so. Here, the women are very much a product of their upbringing in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign. As the daughters and wives of successful merchants or entrepreneurs, their educations have been in the social graces far more than in academic learning as they ready themselves for their perceived roles in society as the wives of successful men and mothers of a new generation of Australian gentry.

Australian Patrick White’s genius for story-telling is on full display in this big,old-fashioned saga filled with intriguing characters exploring the difficult terrain of their inner lives. For a number of characters, all male, that personal inner journey is also part of a daring adventure they make into the interior of Australia in the mid-nineteenth century, an area previously unexplored by the white people who have recently discovered this continent. The female characters in Sydney during this same period have a far more difficult time exploring their inner natures, even in the unlikely event that they might be interested in doing so. Here, the women are very much a product of their upbringing in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign. As the daughters and wives of successful merchants or entrepreneurs, their educations have been in the social graces far more than in academic learning as they ready themselves for their perceived roles in society as the wives of successful men and mothers of a new generation of Australian gentry.

Patrick White, 1988.

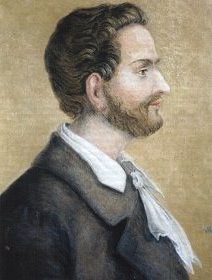

Despite the time, setting, vibrant descriptions of nature, and love story, this novel is far from a romantic extravaganza, due in large part to White’s choices for his two main characters, Johan Ulrich Voss, a German immigrant (modeled on the real explorer Ludwig Leichhardt from Prussia), and Laura Trevelyan, an orphan who has come to Australia from England to live with the Bonners, her aunt and uncle and their family, in Sydney. Voss, whose father tried in vain to turn him into a physician, has become a botanist instead, but “Finally, he knew he must tread with his boot upon the trusting face of the old man his father” and escape not only his parents’ control of his life but the limitations of Germany for a botanist interested in finding new species. It is Laura’s Uncle Bonner who has agreed to provision the ship which will take Voss and a handful of men to Newcastle for the first stage of an exploration across the continent.

Ludwig Leichhardt, the Prussian explorer whose story inspired this novel.

Laura, who meets Voss the week before he is to sail, is not a coquette. Rather, she is regarded by the Bonners’ friends as attractive, though not beautiful, quiet and studious rather than flirtatious. More importantly, she is better educated and far more intellectual than her peers, and she sees no need to pretend – or to change. Her initial conversations with Voss intrigue her, though she is not particularly attracted to him, nor he to her. He regards her as a “cold, hard girl, and I could almost love her.” Their meeting, however, has complex and subtle undertones, and they connect somehow on levels beneath the surface. Ultimately, he tells her that “Your future is what you will make it. Future is will.” After he departs on his explorations, they begin a correspondence. Both are lonely, and separately they begin imagining a life together, even connecting from afar on a spiritual plane during times of sickness and danger, in which each sees visions.

Point Piper, where the Bonners and the Pringles attend a grand picnic.

White develops their story by alternating their two points of view – Voss and his men, as they travel across the north of the country, experiencing almost unconscionable privations, and Laura as she tries to find some kind of purpose among the ladies of Sydney, a place she considers “foreign and incomprehensible.” The six men traveling with Voss have individual reasons for wanting to make this journey. Frank LeMesurier, who writes poetry, for example, tells the ornithologist Palfreyman, “You are an old hand, and cautious, whereas I am a man of beginnings. They are my delusion. Or my vice…I am always about to act positively. There is some purpose in me, if only I can hit upon it.” Judd, a former convict is willing to give up his homestead and his family for this trip. His life, he says, “is not mine any more than that gold chain…And when they would take the cat-[o’-nine-tails] to me, I would know that these bones were not mine, neither…I have nothing to lose, and everything to find.” Brendan Boyle, who runs the provisioning station in Jildra and lives in a dirty hovel, explains this lure of the unknown: “It is the apparent poverty of one’s surroundings that proves in the end to be the attraction…to explore the depths of one’s own repulsive nature is more than irresistible – it’s necessary.”

Darling Downs, Queensland

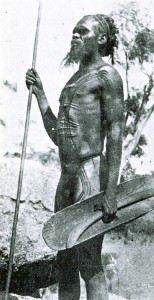

Voss’s trials are epic; the problems among his men as they must eventually find almost non-existent food and water in the desert interior are legion. Throughout all their privations, the author shares their philosophical queries about life and its meaning, and the grand questions of the universe which become more pressing as their circumstances become more dire. With a sense of irony, White introduces two aborigine men who accompany the expedition as guides, and then depicts aborigine groups living relatively successfully in the interior even as the explorers themselves are starving. The apparent simplicity of the aborigines does not preclude a complex value system celebrated in rock paintings and ceremonies filled with respect for nature, and the aborigines’ experience with the few whites with whom they have had contact has made them careful observers of Voss and his crew, wary of their intentions, always on their guard.

Aboriginal man, photo from the late 1800s.

Laura’s life, domestic and social, involves her own trials, one of which culminates in a daring but deeply felt decision in which she assumes a role which no one else among her social set has ever dreamed of accepting – and which will end any possibility of her becoming part of traditional Sydney life. She endures and even thrives, however, because she has discovered her “genius.”

Though this novel occasionally bogs down as the characters examine the minutiae of their thoughts and feelings while disasters are unfolding around them, White has created a complete and complex story of Australia which few readers will forget. The novel is satisfying on every level, thematically, historically, and emotionally, and the characters are memorable. His descriptions are unparalleled, especially in the clever, often satiric presentations of some of the more unpleasant characters, introduced only briefly. As White brings the story of the expedition up to date in the conclusion, just two or three years after the expedition has begun, he resolves many questions, and in the final chapter, an epilogue which takes place twenty years later, he shows how his characters have dealt with their lives. In a witty and ironic scene with a pompous visitor to Sydney from England, Laura ultimately sums up her philosophy: “The little I have seen is less, I like to feel, than what I know. Knowledge was never a matter of geography. Quite the reverse, it overflows all maps that exist. Perhaps true knowledge only comes of death by torture in the country of the mind.”

ALSO by Patrick White: RIDERS IN THE CHARIOT , THE VIVISECTOR and THE HANGING GARDEN

Photos, in order: The photo of the author, by Barry Jones, is found on http://www.abc.net.au

The drawing of Ludwig Leichhardt is from http://en.wikipedia.org

Eliza Point in Old Sydney Town, called Point Piper at the time of this novel, may be found on http://bibliodyssey2lj.livejournal.com

The topography of Darling Downs, where most of this journey takes place, may be seen here with its crop of sunflowers in the distance: http://en.wikipedia.org

The aboriginal man is shown on http://www.janesoceania.com