Note: Patrick White was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973.

“[Mrs. Bulpit’s] forearms, hands, and face could have been moulded from natural marzipan. The lips shone with crimson grease rising to a little bow, they matched the nails in the marzipan hands…The coulour of her hair made Mrs. Bulpit noticeable, the little curls with which her head was arranged were of a rich red such as you see in a windowful of new furniture.”

When Eirene Sklavos, a school-age child, sees Mrs. Bulpit for the first time, she has not even started to come to terms with the fact that her mother will be leaving her with Mrs. Bulpit indefinitely. Having traveled with her mother from Greece to Australia to escape the horrors of World War II, Eirene has already dealt with the death of her father, a communist fighting for what he and his wife believe to be a better world for Greece. Almost immediately after Eirene meets Mrs. Bulpit for the first time, her mother departs Australia for Alexandria, Egypt, where she plans to continue her political efforts. Alone in a foreign country, Eirene will have to learn the hard way who she is and where she belongs. She soon meets Gilbert Horsfall, a boy her own age, who is also living with Mrs. Bulpit, though his trip to Australia from England has taken much longer. His father is working in New Delhi; his mother is dead. He, too, has growing pains, and he, too, is a foreigner to Australia. The degree to which the two children may be able to help each other is a question for much of the novel, as are the effects of uncontrollable outside forces on their lives as they grow and learn.

When Eirene Sklavos, a school-age child, sees Mrs. Bulpit for the first time, she has not even started to come to terms with the fact that her mother will be leaving her with Mrs. Bulpit indefinitely. Having traveled with her mother from Greece to Australia to escape the horrors of World War II, Eirene has already dealt with the death of her father, a communist fighting for what he and his wife believe to be a better world for Greece. Almost immediately after Eirene meets Mrs. Bulpit for the first time, her mother departs Australia for Alexandria, Egypt, where she plans to continue her political efforts. Alone in a foreign country, Eirene will have to learn the hard way who she is and where she belongs. She soon meets Gilbert Horsfall, a boy her own age, who is also living with Mrs. Bulpit, though his trip to Australia from England has taken much longer. His father is working in New Delhi; his mother is dead. He, too, has growing pains, and he, too, is a foreigner to Australia. The degree to which the two children may be able to help each other is a question for much of the novel, as are the effects of uncontrollable outside forces on their lives as they grow and learn.

Developing his themes of identity and connection (or lack of it) in an unfinished book that he never tried to publish, author Patrick White keeps his story line simple, but psychologically astute, using children as the main characters as he explores a variety of writing techniques that are not obvious in the bold, fairly straight-forward narrative style of his famous earlier novels. Readers of this book, which White started in 1981, may be astonished to see just how experimental this book is, compared to Voss (1957), Riders in the Chariot (1961), and The Vivisector (1970). It very nearly remained unpublished and unknown. White had indicated before his death in 1990 that he wanted all his incomplete works destroyed, but though he did destroy many letters and other writing over the years, and had the opportunity to destroy this work, he let it remain intact during his lifetime. It was not until 2010 that his executor, Barbara Mobbs, began to consider the possibility of allowing this book to be published, and then gave her permission.

The result is a rare opportunity to read a hand-written and personally edited novel by Nobel Prize winner Patrick White, which, in addition to being a good story, provides a rare, direct insight into how he thinks and how he creates a draft. The novel, according to David Marr, who wrote the Afterword, was intended to be presented in three parts, of which this manuscript was to be Part I. Though the ending of the novel as we see it here is a bit “thin,” compared to the earlier part of the book, White has a clear sense of direction with his story and his characters while leaving his multiple, constantly changing points of view and his use of stream of consciousness intact. Readers who have read only White’s earlier works may find that it is this aspect of the book which is most fascinating.

The novel opens with the meeting of Mrs. Bulpit and Eirene’s mother, which the reader observes from the mother’s point of view. A page or two later, Eirene’s own observations become dominant, before the point of view moves back to her mother’s, and then forward again to her own. By page six, White is introducing Gilbert Horsfall and his point of view, as Gilbert thinks about introducing himself to Eirene and her mother, before he suddenly remembers the bombings in London and the death of his best friend. As quickly as changes occur in one’s own musings, Gilbert then recalls his voyage from England to the United States and his travels across the United States to the West Coast before his journey to Australia, all this in just a few pages. White also inserts the points of view of those who accompanied Gil, both the adults and the other children on the trip.

The constantly shifting points of view take some getting used to. Initially, these are not clearly delineated and the reader knows nothing about the individual characters to give clues as to who is “speaking.” Gradually, Eirene and Gil begin to emerge as their own persons, and the reader begins to understand their backgrounds, their memories of “home,” and their reactions to what is happening to them. Sometimes, the points of view change several times within a single paragraph: In this example, Mrs. Lockhart (Eirene’s aunt, who has arrived at Mrs. Bulpit’s house to say goodbye to Eirene’s mother), along with Eirene’s mother, and Eirene herself all share a paragraph:

“Well, Ireen [sic] can depend on me. Couldn’t have her in my own house – four boys – and Harold didn’t want to risk a girl…Why are you not in bed, Eirinitsa? Mamma is crying as you stand in the door like a wax figure, eyes closed, leaving anger and discipline to Papa. You could feel Papa hated you, for that moment, anyway. Will Aleko, his closest friend, hate too if he catches you staring at the wax figures?”

Two paragraphs later, White introduces stream-of-consciousness:

“Looking back from where you have dropped on your knees on something sharp it no longer matters worse blood could not be drawn the sisters have arrived at the window and stand looking out a fright or at least suspicion has shut them up for the present they stand in the wreckage of their principles…”

White’s gift for description keeps the reader engaged, even when the changing points of view and the narrative line may be challenging. His realistic depiction of the children, who act like children throughout, even as they question who they are and where they belong, give a liveliness to the novel which benefits from the novel’s experimental style. This work is a major contribution to the understanding of Patrick White and his writing, and readers familiar with White’s earlier work will treasure the new insights they gain here while they enjoy the characters and empathize with their struggles.

ALSO by Patrick White: VOSS (1957), RIDERS IN THE CHARIOT (1961) and THE VIVISECTOR (1970).

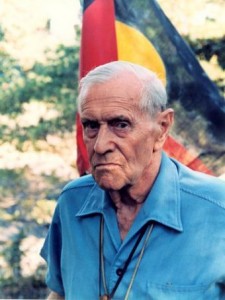

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, by Barry Jones, is found on http://www.abc.net.au

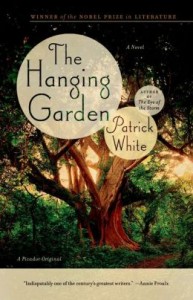

The treehouse appears on http://fellowshipofminds.wordpress.com

ARC: Picador