“So this is what the process of globalization looks like? The whole world will become a village?…If this is really the case, then why does Dr. Watson want to get out of here as fast as possible? Why does Sapam Tomba stand mute?…Why are non-Bengalis afraid in Calcutta and non-Marathis afraid in Mumbai? Why was the Christian minister Staines burned alive in his car…? Why have the few Hindus of Kashmir…become refugees, lost, wandering from door to door?”

If you came to this review because the title suggests that this is a romantic, even pretty, little novel of love in exotic India, then you will be shocked by what you discover here. This is a tough novel depicting what author Uday Prakash, controversial in his own country, sees as a major hurdle for India – not necessarily in the major cities so much as in the rural countryside. The economic changes in India in the 1990s have brought about a thriving middle class and a vibrant life in the cities, much of it “American style,” but those changes do not translate into similar changes in rural states, where traditional ways of life continue, including dramatic contrasts between the wealthy Brahmin class, which still controls the economic, political, and intellectual life of many areas, and the non-Brahmins who seem unable to rise, no matter how hard they try, because those very Brahmins also control most of the opportunities.

If you came to this review because the title suggests that this is a romantic, even pretty, little novel of love in exotic India, then you will be shocked by what you discover here. This is a tough novel depicting what author Uday Prakash, controversial in his own country, sees as a major hurdle for India – not necessarily in the major cities so much as in the rural countryside. The economic changes in India in the 1990s have brought about a thriving middle class and a vibrant life in the cities, much of it “American style,” but those changes do not translate into similar changes in rural states, where traditional ways of life continue, including dramatic contrasts between the wealthy Brahmin class, which still controls the economic, political, and intellectual life of many areas, and the non-Brahmins who seem unable to rise, no matter how hard they try, because those very Brahmins also control most of the opportunities.

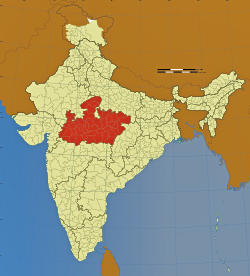

A sweet love story between Rahul, a non-Brahmin student at a university in the state of Madhya Pradesh, and Anjali, the Brahmin daughter of the state minister of Public Works, provides the framework through which the author illustrates what he sees as a cultural crisis for the next generation. Madhya Pradesh, in the center of India, is “one of the least developed states in India,”* and its isolation from the major economic trends allows its ingrained, traditional ways of life, going back centuries, to continue. Within this seemingly simple love story, author Prakash asks whether the economic good news of the past twenty years, as we see it in Mumbai and New Delhi, will eventually dominate the country as a whole, or whether the struggles of those left out of the “success story” and its “progress,” by virtue of their lack of “status,” will eventually be heard. Which group will succeed, “the one with a Pepsi in hand, half-naked model on his arm, Visa card in the pocket, or…the one with red eyes, whose parents have been plundered for fifty years by successive regimes, who has a weapon in hand and is killed every day in ‘encounters’ [with police and security forces]”?

A sweet love story between Rahul, a non-Brahmin student at a university in the state of Madhya Pradesh, and Anjali, the Brahmin daughter of the state minister of Public Works, provides the framework through which the author illustrates what he sees as a cultural crisis for the next generation. Madhya Pradesh, in the center of India, is “one of the least developed states in India,”* and its isolation from the major economic trends allows its ingrained, traditional ways of life, going back centuries, to continue. Within this seemingly simple love story, author Prakash asks whether the economic good news of the past twenty years, as we see it in Mumbai and New Delhi, will eventually dominate the country as a whole, or whether the struggles of those left out of the “success story” and its “progress,” by virtue of their lack of “status,” will eventually be heard. Which group will succeed, “the one with a Pepsi in hand, half-naked model on his arm, Visa card in the pocket, or…the one with red eyes, whose parents have been plundered for fifty years by successive regimes, who has a weapon in hand and is killed every day in ‘encounters’ [with police and security forces]”?

Madhya Pradesh, in the center of India, has been described as "one of the least developed states in India."

Rahul, who begins his university studies as an organic chemistry major, quickly changes to anthropology, and when he first catches sight of the beautiful Anjali Joshi, changes again to Hindi, her major, which, for most other students, would be regarded as the “kiss of death.” “No one really knew for sure why [this] department existed at all…Those boys were ragged, misfits, backward, isolated from the real world, and their teachers made for the same caricature. One student would shamelessly scratch his crotch in public, while another shaved-head dhoti-clad type would ogle some girl like a chimpanzee.” All but Rahul and two others are Brahmins, and all the faculty are Brahmin. Even knowing this, Rahul still has no clues as to his future difficulties. He quickly learns, however, that goondas, some of them supported by government officials and their minions in the post office, know when students will be receiving money from home and then show up for their “cut.” These goondas “could break in at any moment and put a gun to your head. We are merely prey, living in a cruel, criminal, and degrading time. It’s an age of thugs, counterfeiters, smugglers, and real-estate developers. Nowadays, righteous and upstanding Indians suffer under this regime as if they were Kashmiris, Manipuris, or Naxalites.”

Banding together against the “goondas,” the students form the SMTF, the Special Militant Task Force, and prepare to strike back. Their computer skills allow them access to information which shows how widespread the corruption is and how many in the university administration are part of the conspiracy. As one of Rahul’s friends points out, “There’s a part of our society afflicted by a superiority complex. The Great Indian Puritanical Sectarian Casteist Hedonist Homogeneous Middle Class. In that same family you’ll find a white, a black, a light brown, a dark brown, a flat nose, a big lips, a long and thin nose, a round eyes, a fine brow, a yellow face. Ha! Everything’s mixed in there.” Bottom line, trust no one.

The suicide of one student causes Rahul to wonder “if it’s true that all former frames of reference are now immaterial, and if it’s true we’ve reached the end of history….[Is this] a new world, a new world order where the entire terrain of the past is irrelevant?” As Rahul contemplates the future, he also ruminates on the past: “The Parliament of India has been filled with killers, smugglers, lackeys of foreign companies, profiteers, black marketers – all dishonest…The prime minister was going to jail. Embezzlement, corruption, and thuggery cases were pending against multiple state chief ministers. The judge was on the take. Police were in cahoots with criminals, and each day of the turn of the century was smeared with the blood of innocent, honest, justice-seeking Indians.”

The President's House in New Delhi, built by British architect Edward Lutyens, is regarded by many as a symbol of the British occupation, and, as indicated in this novel, many want this building replaced.

Eventually, Rahul and Anjali themselves reach the crisis point and must make their own decisions regarding the future, keeping in mind all the traditional family objections, the problems associated with their limited opportunities and their lack of achievements, and how all those issues affect any chance they may have for future success.

An unusual novel in which plot is subordinated to message without overwhelming the reader with moralizing, The Girl with the Golden Parasol recreates life in rural India during the beginning of the twenty-first century. Long-time traditional values are distorted by dishonesty and petty actions by police and officials who feel threatened on the local level, creating a new immorality which makes life impossible for those non-Brahmin citizens living on the “outside.” Translator Jason Grunebaum, who has geared his translation for an American audience, also recognizes its importance for other English speakers, including some in India, and his translation is lively and informative without becoming ponderous, with a message that rings clear.

*The quotation about Madhya Pradesh as “one of the least developed states in India” appears on Wikipedia.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://commons.wikimedia.org

The map of Madhya Pradesh is from http://en.wikipedia.org

The iconic neem tree may be found here: http://getmuchinfo.blogspot.com

The President’s House and the arguments surrounding it may be found on http://india.blogs.nytimes.com

ARC: Yale U. Press