“You’re a crow with an ear for a beak. No one can understand this story. And no one would want to. It’s useless. Only the edifying fable with its moral will remain, only the husk of the facts, the pornography of horror…But what gave it meaning, what made it human—that dies with us…In the end what you’re looking for is a moral adventure tale. That’s what will get you a publisher.”–Lorena, to her interviewer.

Addressing a “hypocritical reader, my double, my brother,” a former revolutionary from Chile has been asked to tell her story to a writer investigating the human rights abuses that occurred in Santiago in the 1970s. The writer has traced her from Chile to a hospice in Stockholm, and the woman, Lorena, has consented to being interviewed, though she fears that he will reduce her story to a “moral adventure tale.” She is old and dying, but she has a long history, and as she begins her story, we see her back in the years just before the death of then-President Salvador Allende (in 1973). She is young – a new, unmarried mother. Her parents have divorced, her lover has disappeared, and she is rootless, except for her commitment to her child. Like many of her peers, she believes in the socialist goals of President Allende, who is committed to improving the lives of the poor, and she worries about the repressive military which is challenging him directly and working to suppress the Marxist rhetoric so rampant in universities, where she and other students espouse it.

Addressing a “hypocritical reader, my double, my brother,” a former revolutionary from Chile has been asked to tell her story to a writer investigating the human rights abuses that occurred in Santiago in the 1970s. The writer has traced her from Chile to a hospice in Stockholm, and the woman, Lorena, has consented to being interviewed, though she fears that he will reduce her story to a “moral adventure tale.” She is old and dying, but she has a long history, and as she begins her story, we see her back in the years just before the death of then-President Salvador Allende (in 1973). She is young – a new, unmarried mother. Her parents have divorced, her lover has disappeared, and she is rootless, except for her commitment to her child. Like many of her peers, she believes in the socialist goals of President Allende, who is committed to improving the lives of the poor, and she worries about the repressive military which is challenging him directly and working to suppress the Marxist rhetoric so rampant in universities, where she and other students espouse it.

When a university friend takes her to a political demonstration in Santiago, she soon finds herself “caught up in something big, an enormous collective body; we sang together and I was part of the hope harbored by those who suffered, the poor of the earth.” She eventually becomes an active participant with this group, the Red Ax, going to “meets” and camps, studying and arguing about Marx and Lenin and other revolutionary philosophers, developing a sense of purpose, and becoming attracted to some of the committed young men she meets as they jointly plan anti-establishment attacks. Her attraction to one young man “was my rite of initiation, and [was] how I began the difficult process of self-elaboration that is necessary in order to embrace a moral asceticism,” she tells her intervewer. “In those dark years,” she says, “belonging to that family, that secret and forbidden family that I had chosen, was to be born again, and to be prepared for the sacrifice, anytime, anywhere.”

After her torture, Lorena returns to her mother's home, where the apricot tree outside her window becomes a comfort - a reminder of her past.

Lorena’s story must be pieced together from episodes taken out of their natural chronology, as the narrative jumps around in time. In the opening pages, which take place three or four years after she begins her connections to the Red Ax, Lorena quickly captures the interest of the writer of her story (and the reader) by using strong and dramatic imagery of her running for her life from the Currency Exchange, with $30,000 in her purse. For reasons that she can never explain, even to herself, she dives under a truck at the very moment when she could have escaped, and is captured. Her torture by the authorities begins immediately, and it is torture so brutal it defies comprehension. Lorena has been working as a French teacher by day and going to “meets” secretly at night, a particularly dangerous activity in the years after General Augusto Pinochet’s seizure of power from President Allende in a military coup in 1973. Determined to wipe out all traces of President Allende’s socialism, and all leftist ideology, Pinochet rules through fear, maintaining iron control with the support of the military, the national police, and paid thugs who do not hesitate to use the most sadistic of tortures to maintain their power.

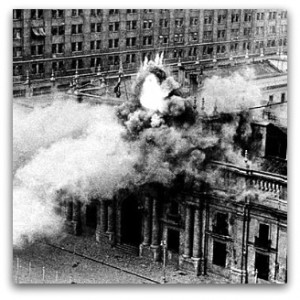

The burning of La Moneda, the Presidential Palace in a military coup, led to the suicide of President Salvador Allende on Sept. 11, 1973.

Though others in the Red Ax cell have sent their young children to Cuba to be educated in an environment they consider safer than Santiago at this time, Lorena has not yet sent her daughter Anita, now age five, who lives with Lorena’s mother. She soon regrets this. Less than three months after her first interrogation and torture, she is picked up again, and this time, her daughter’s safety is used as the “bargaining” tool during her questioning. If she does not give her interrogators everything they want, they will hurt her daughter. Not surprisingly, Lorena’s commitment to abstract principles fades under these real-life threats. Forever afterward, she will lead a double life—one in which she works with the enemy at the same time that she tries to remain friends with her Red Ax comrades.

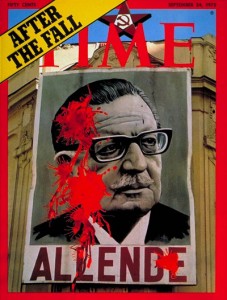

Time Magazine (Sept. 24, 1971) contains details of the attack on Salvador Allende and the aftermath. Cover by Carl Roodman.

Chilean author Arturo Fontaine, who is on the Board of Chile’s Museum of Memory and Human Rights, creates a novel which emphasizes the psychological strains on basically honest people who, like Lorena, are forced to see beyond the black and white positions on which so many others base their stands. Fontaine uses subtlety as he creates the character of Lorena and then depicts her agonizing over her decisions. Readers will empathize with her, recognizing some of the turning points at which she may have made the wrong decisions, while, at the same time, understanding the pressures which have led to her decisions. As she tries to protect her interests on both sides of the political spectrum, quietly revealing some information while withholding other information, Lorena eventually finds herself admitting, “I’m the one I want to erase from my life. Forgive myself? How could I give myself something I don’t deserve? Unhappiness has been my god.”

Lorena's lover in Stockholm introduces her to Rauschenberg's "Monogram," a piece in which a goat is constrained by an automobile tire. For more info, double-click on the photo.

Author Arturo Fontaine writes a novel in which the action takes place between 1972 and 1977, and is then revealed by Lorena in the present day, a technique which increases the reader’s involvement in events which occurred a generation ago. This is not a novel that depicts the outrages of the Pinochet regime – there are already plenty of those – so much as it is a novel of people who happen to live in Chile at the junction of the regimes of both Salvador Allende and Augusto Pinochet, poles apart politically but conjoined chronologically. As a result, the novel avoids most of the predictable violence and allows the reader to explore the depths of a character’s inner conflicts. The novel is dramatic and thoughtful, thanks, in part to the sensitive translation by Megan McDowell, and Fontaine’s insights into Lorena’s psychological changes, often subtle, make this novel of double lives an intense and even personal experience.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.letralia.com/

The apricot tree may be found on http://www.daleysfruit.com.au

The Presidential Palace in flames (Sept. 11, 1973) appears on http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/

The Time Magazine cover, designed by Carl Roodman, may be accessed here: http://www.time.com

Robert Rauchenberg’s “Monogram,” a goat constrained by a rubber tire, exhibited at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, is featured in an article here: http://www.greynotgrey.com The quotation from ArtNet (below the photograph in the link) regarding the “barbarism” of the painting makes this image particularly relevant to the action in this novel.

ARC: Yale U. Press