“Mourning, thought Albert, is nothing but a word. People contrived it to make things simpler. But what you actually feel for the dead isn’t sorrow, isn’t pity either—what hurts so [effing] bad when someone disappears forever is nothing more than the realization that you’ve been alone from your very first day in this world, and that you’ll stay that way till the end.”

In his third book, the first  to be published in English, German author Christopher Kloeble creates a thematically complex novel in which he examines the most crucial aspects of everyday life for several families over several generations as they try to figure out who they are and what their roles are within their own family histories and in the histories of others close to them. Though most thoughtful people reflect on their parents and siblings and their own roles within their families as part of their growing-up process, the relationships in this novel are not as clear-cut as they are in most readers’ lives. Even the question of who is your father or who is your mother does not inspire an automatic answer for some of the characters here. As Kloeble examines three generations of characters in two story lines, from the aftermath of World War I to the present, the exact nature of their connections is often hidden, not only from the reader but also from the characters themselves.

to be published in English, German author Christopher Kloeble creates a thematically complex novel in which he examines the most crucial aspects of everyday life for several families over several generations as they try to figure out who they are and what their roles are within their own family histories and in the histories of others close to them. Though most thoughtful people reflect on their parents and siblings and their own roles within their families as part of their growing-up process, the relationships in this novel are not as clear-cut as they are in most readers’ lives. Even the question of who is your father or who is your mother does not inspire an automatic answer for some of the characters here. As Kloeble examines three generations of characters in two story lines, from the aftermath of World War I to the present, the exact nature of their connections is often hidden, not only from the reader but also from the characters themselves.

Author photo by Stephan Rohl.

In simple, clear language which befits the two main characters as the novel opens, Kloeble introduces Albert, an orphan who is now nineteen years old. Every year since he was three, Albert has traveled from the orphanage where he grew up, far from the town where he was born, to visit a man named Fred from his “home town.” As the novel opens, he has just arrived once again, after a seventeen-hour bus ride to the small community in the Bavarian uplands where the now-sixty-year-old Fred lives. From his earliest years of visiting, Albert has understood that when they are together, he is responsible for Fred’s well-being: Fred is a “kloble,” a person who is “clumsy” and limited in intellect. On his present trip, however, Albert feels as if he has come “home” for the last time to the place where his only family – still a mystery – once lived. He will watch over Fred, whom he believes to be his father, through Fred’s final illness. Fred has only five months left to live.

“Mint green” BMW 3-series from 1936. A dilapidated version of a car like this keeps Fred amused outside his house.

Gradually, Fred’s life becomes clearer. He is a hero in the town, having saved a woman and her baby on “The Day the Bus Attacked the Bus Stop,” a time when a runaway bus almost killed them, and the town honors him for that. He has always loved reading the Silver Encyclopedia though he does not comprehend what it means, and he delights in sitting beside the road counting cars, especially mint green cars like his favorite model, a BMW from the 1930s, one of which, now a dilapidated wreck, sits beside his house. During these hours of counting, Fred regards his life as “ambrosial.”

Every year the town’s the most important celebration is the Sacrificial Festival in which each resident submits his/her “Most Beloved Possession” to be burned, and on his visits, Albert always searches Fred’s house and attic for any little piece of information which might provide a clue as to who his own mother might be. Anything he can find, no matter how small, would be Albert’s Most Beloved Possession; Fred’s Most Beloved Possession, one which he treasures, is a gold nugget so large it has the value of a new house, one he says he received from his father.

Fred explores the sewers where he claims he finds a series of magical treasures left in a box by his father.

Through flashbacks, a second point of view appears at the beginning of Part II, illustrated visually by italicized print whenever this speaker confides in the reader. This character, a male, has memories and family history which go back to the early twentieth century, and the reader soon learns that this speaker, Julius Habom, is the grandson of Anne Marie Habom and Nick Habom, and the son of their son Josfer. The two story lines, that of Fred and Albert, as they try to deal with Fred’s imminent death, and that of Julius and his offspring, are told in parallel, and the changes in story, time period, and focus keep the reader busy noting and tracking the hints and clues regarding Albert’s mysterious origins, and the Habom family’s relationships over time. Some story elements, such as Fred’s interest in exploring the local sewer system in search of his father, whom he believes puts wonderful surprises inside a box which Fred keeps in the sewer, add to the mysteries and suggest symbols, though they do sometimes create confusion for the reader with their complications and suggestions of the supernatural.

During this novel, the author explores some of mankind’s most important themes in unique ways. Who are we as individuals (a question raised by Albert and sometimes Fred) exists alongside questions about who we are within our families and what is the role of love in our lives. What obligations, if any, do we have toward a new generation, and to what information is that new generation entitled by their elders? How, if at all, is the present a direct outgrowth of the past? As Albert begins to grow up and feel the stirrings of love and sex, he also experiences three serious loves, another complex theme well developed through the action, in addition to more platonic loves which teach him about humanity. And slowly, as Fred weakens, death becomes a major theme, making Albert increasingly determined to find out who his parents are before it is too late. No matter what he discovers, however, Albert knows he will always regard Fred as his father, despite Fred’s limitations.

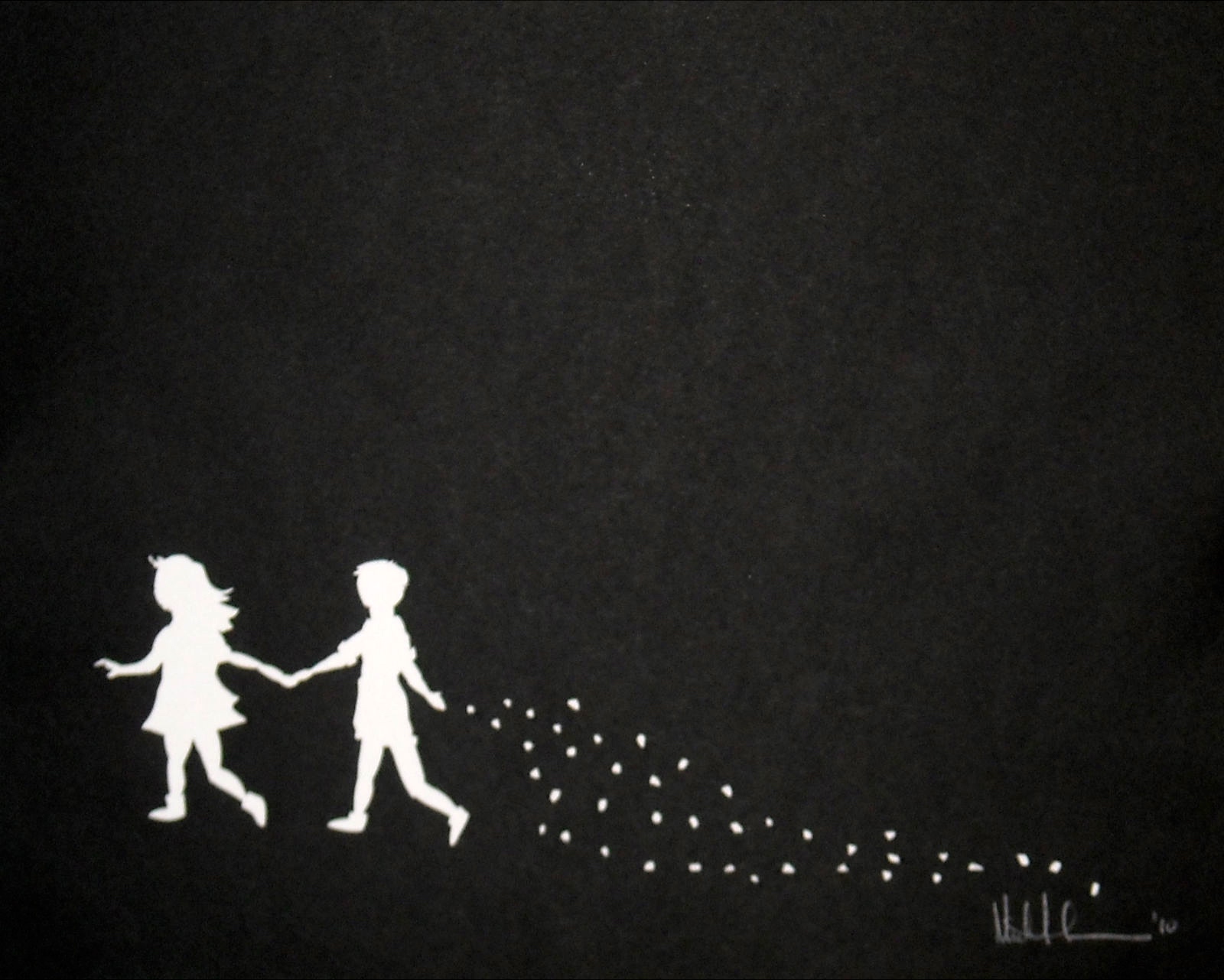

Near the end of the novel, a “shape-shifter” appears, adding to the hints of supernatural elements, and a villain enters the novel for the first time, focused on hurting Fred. The novel continues inexorably forward through the generations until all questions regarding mothers and fathers and children and their heritage are finally resolved. Carefully constructed in terms of the parallel story lines and the detailed and unusual chronological shifts, the novel contains many diversions and sidetracks, which often add to the themes while reducing the reader’s identification with the characters and their ability to share their emotional worlds. Life, as one character believes, “was a heap of puzzle pieces that never added up to one great whole…merely filled you with false hope…let you believe that the Truth existed out there…puzzle pieces…Hansel and Gretel crumbs.” A patient reader will consider that as Kloeble expertly guides his novel to its final resolution.

Near the end of the novel, a “shape-shifter” appears, adding to the hints of supernatural elements, and a villain enters the novel for the first time, focused on hurting Fred. The novel continues inexorably forward through the generations until all questions regarding mothers and fathers and children and their heritage are finally resolved. Carefully constructed in terms of the parallel story lines and the detailed and unusual chronological shifts, the novel contains many diversions and sidetracks, which often add to the themes while reducing the reader’s identification with the characters and their ability to share their emotional worlds. Life, as one character believes, “was a heap of puzzle pieces that never added up to one great whole…merely filled you with false hope…let you believe that the Truth existed out there…puzzle pieces…Hansel and Gretel crumbs.” A patient reader will consider that as Kloeble expertly guides his novel to its final resolution.

Photos, in order: Author photo by Stephan Rohl on https://commons.wikimedia.org

Fred’s favorite car, a mint-green 3-series from the 1930s, is shown on this site: http://www.prewarcar.com/classifieds/ad177815.html

Fred enjoys escaping into the town sewers where he sometimes finds seemingly magical presents left in a box, he believes, by his father. http://www.gizmodo.com.au/

The lovely woods of rural Segendorf are featured on this tour site: http://trip-suggest.com

The drawing of Hansel and Gretel and their crumbs is shown on https://www.seowerkz.com

ARC: Graywolf