“I have been wandering through mining country, a man in exile, a castaway, a snake wriggling out of its skin….I walk the landscape, I sit by the mine, in the cemetery, in the open fields covered with soot, unaware of the time, guiding myself only by the movement of the sun. I carry stacks of paper and occasionally sketch on my knees…Often, after I have done so, I tear up the paper and let the wind carry the strips away.”—Vincent Van Gogh, letter to Theo, Prologue, 1879.

Artist Vincent Van Gogh’s earnest attempts to live a productive life while also burdened by crushing sadness and isolation come to life through author Nellie Hermann’s insightful depiction of his life as a missionary in a coal mining village. Depicting Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) before he became an artist, she focuses on the period of 1879 – 1880, when Van Gogh was living in the remote Borinage mining area of southwest Belgium, near the French border. The young son of a Dutch Reformed preacher, the twenty-seven-year-old Van Gogh had worked for several years in the Goupil & Cie gallery and its showrooms in the Hague, London, and Paris, before studying theology to become a minister and missionary, like his father. His long, descriptive letters to his younger brother Theo, used as resources by the author, provide intimate glimpses of his life in the Borinage, including the misery he shared with the miners and their families, which his own depression may have exacerbated. Though he loved art, he did not exhibit the kind of talent in his own work which would have made him successful, at that time, and he had failed both his theology exam and his course at a Protestant missionary school before heading to the Borinage on his own religious mission. His father, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, considered him an “idler.”

Artist Vincent Van Gogh’s earnest attempts to live a productive life while also burdened by crushing sadness and isolation come to life through author Nellie Hermann’s insightful depiction of his life as a missionary in a coal mining village. Depicting Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) before he became an artist, she focuses on the period of 1879 – 1880, when Van Gogh was living in the remote Borinage mining area of southwest Belgium, near the French border. The young son of a Dutch Reformed preacher, the twenty-seven-year-old Van Gogh had worked for several years in the Goupil & Cie gallery and its showrooms in the Hague, London, and Paris, before studying theology to become a minister and missionary, like his father. His long, descriptive letters to his younger brother Theo, used as resources by the author, provide intimate glimpses of his life in the Borinage, including the misery he shared with the miners and their families, which his own depression may have exacerbated. Though he loved art, he did not exhibit the kind of talent in his own work which would have made him successful, at that time, and he had failed both his theology exam and his course at a Protestant missionary school before heading to the Borinage on his own religious mission. His father, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, considered him an “idler.”

The Prologue of this novel, set in September, 1879, shows clearly the conflicts the young Van Gogh feels as he writes a letter to his brother Theo, though the reader does not yet know the nature of all these conflicts. The quotation which opens this review then expands as Van Gogh further explains that he is not “idling.” He has been trying to “be patient, to be calm, to make no sudden moves. I am trying to do things right this time,” he says, “to listen, to hear, to see. Great forces are shifting in me; I must let them take their time….I feel I can see the road ahead.” If he has changed, he believes, it is because of what he has already been through in the Borinage, and he is desperate to share his experiences with Theo, who has recently visited him after a long period of silence.

Though Van Gogh unburdens himself here in the opening scenes, the reader does not get the immediate satisfaction of an answer from Theo, however. Instead, the author toggles the time frame between 1879 and 1880, employing two points of view which create a broader picture of Van Gogh’s life. In the 1879 sections, Van Gogh reveals his intense feelings. In the 1880 sections, which alternate with the 1879 sections, the author uses a third-person point of view to give a wider, more objective perspective and, sometimes, to follow up on some events while maintaining suspense about the developing action and other events. These objective sections confirm many of Van Gogh’s observations, allowing the reader to connect the outcomes with Van Gogh’s earlier feelings or to see how life has moved on. Since the reader approaches Van Gogh’s letters to Theo from a distance of almost one hundred thirty years and, presumably, already knows the inevitable end of Van Gogh’s story, the author’s technique is particularly effective, since the letters give immediacy and intensity to Van Gogh’s inner struggle without allowing the book to become overtly sentimental or feel exaggerated.

Anonymous drawing of the crowded Goupil and Cie gallery, where Vincent Van Gogh and later his brother Theo worked.

Having introduced Van Gogh’s mental state in the Prologue, the author opens the story a year later – in May, 1880 – as Van Gogh is walking the 150 miles from the Borinage to Paris in heavy rain to see Theo. Cold, hungry, and exhausted, he collapses and wakes up inside a bale of hay in a barn, covered by a blanket, rescued by a local farmer. He remembers an explosion in a mine, and some people he knew in the village. Then, in an apparent fugue state, he remembers his life with his family, where he was the second son to have been named Vincent Van Gogh after the death of the first Vincent. Since the family went to the cemetery to visit the grave of “Vincent” every Sunday, he has always wondered which of the two Vincents is the “real” one. He feels like a “ghost in human skin.”

A young boy scavenges in a slag heap for enough coal to keep his family warm for a few days. He appears to be barefoot.

A flashback to the 1879 mining life reveals details that are almost as shocking to read as they must have been for Van Gogh to observe. The author gives life to Vincent’s local acquaintances – the sad men, women, and children who work in a terrifying and poorly ventilated mine. Each day they emerge covered with soot, a problem which affects their breathing almost immediately, with children as young as fourteen often having lung disease. Women and young girls also perform laborious tasks deep in the mine – their need to have money for food being the same as that of the men. All the workers look older than their years, many are scarred from accidents, and all are half starved. Van Gogh’s sense of horror is so obvious that a long-time miner cautions him, “If you are going to live here, you need to know the truth….The people here are treated not as men but as animals, and you are to bring us some peace.” He tries, and he goes on to start a school for children, conduct sermons, and run a Bible school one day a week. He cannot help wondering why it is that God wills such vulnerable people to suffer, and, further, why it is that his religious father is not angry about the injustice.

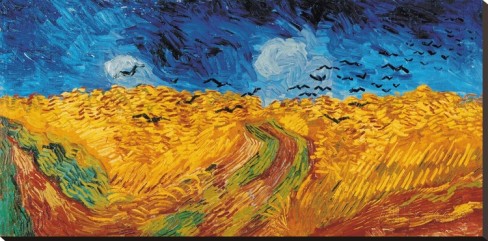

“Crows in Wheatfield,” painted by Van Gogh the month he died, may have been inspired by some of his walks during his time in the Borinage.

Throughout the novel Vincent’s own life develops in great detail, and readers interested in his biography will have plenty to keep them involved and intrigued here. His references to well known paintings of the day which epitomize what he is seeing, and to scenes which he himself eventually brings to life in his own paintings will please art historians. Author Nellie Herman shows him putting his whole heart into his work in the village, giving up everything he can from his own life, including food, so that the miners can benefit. Overwhelmed, he becomes physically and emotionally ill and spiritually at loose ends, requiring intervention from his father and family. His occasional drawings which provide him with some sense of accomplishment, however crude they may be technically, eventually lead him to make significant decisions. The world has been grateful for those decisions ever since. A dramatic and insightful novel of a man whose sensitivity exceeded what his heart and mind could bear.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://forthmagazine.com

Vincent Van Gogh, at age nineteen, when he began working for Goupil and Cie Gallery. http://flashbak.com/

The crowded Goupil and Cie Gallery, drawing by an unknown artist. https://en.wikipedia.org

Young boy scavenges in slag heap for enough coal to keep his family warm for a few days. He appears to be barefoot. http://www.aditnow.co.uk/

“Crows in Wheatfield,” one of Van Gogh’s last paintings, was inspired earlier by some of the scenery he most enjoyed in the Borinage. http://www.allposters.com

ARC: Farrar, Straus & Giroux