Carlos Rodriguez in Lima, masquerading as “Georgina,” to poet Juan Ramon Jimenez in Spain: “Did you not once mention that you are a painter? Imagine, then, that I am giving you instructions for painting a landscape. This beautiful view from the sky over Lima, always misty, changeable, so nurturing of inventions and fantasies…Suppose, if you wish, that we are painting the canvas together. And that my manner of painting it, of adding colors and textures, also creates a sort of portrait of me.”

Delightful, playful, clever, and humorous, Spanish author Juan Gomez Barcena’s debut novel is also consummately literary, telling a story on several levels at once but doing so while maintaining the atmosphere of a college prank. Two university students who are also members of the moneyed elite in Lima, Peru, in 1904, are anxious to obtain the newest book of poetry written by Juan Ramon Jimenez, a much-admired twenty-four-year-old writer in Spain who has been publishing lyrical poetry to international acclaim. Though twenty-year-old Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez consider themselves poets, too, they have been writing to no acclaim; few others from their college find their work interesting or original. Poet Jimenez eventually goes on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956, while no one now remembers the names of Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez, except for their possible creation of a hoax regarding the world-famous poet Jimenez, the hoax described in this book.

Delightful, playful, clever, and humorous, Spanish author Juan Gomez Barcena’s debut novel is also consummately literary, telling a story on several levels at once but doing so while maintaining the atmosphere of a college prank. Two university students who are also members of the moneyed elite in Lima, Peru, in 1904, are anxious to obtain the newest book of poetry written by Juan Ramon Jimenez, a much-admired twenty-four-year-old writer in Spain who has been publishing lyrical poetry to international acclaim. Though twenty-year-old Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez consider themselves poets, too, they have been writing to no acclaim; few others from their college find their work interesting or original. Poet Jimenez eventually goes on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956, while no one now remembers the names of Carlos Rodriguez and Jose Galvez, except for their possible creation of a hoax regarding the world-famous poet Jimenez, the hoax described in this book.

In 1904, Carlos and Jose, frustrated because they have been unable to find a single copy of Jimenez’s latest collection of poems in any bookstore in Lima, decide to write to their idol in Spain and to ask for a copy of this new book. As they begin to write their letter to Jimenez, they realize that no matter how florid their writing or how impassioned their request for a copy of Jimenez’s book, they will probably fail to achieve their goals, even if they “write the most difficult poem of all, one that has no verses but can touch the heart of a true artist.” Then one of them says, idly, “It would be better if we were a beautiful woman, then Don Juan Ramon would put his entire soul into answering us,” a remark which sets the course of their mischief. Carlos pilfers some scented stationery from a sister’s desk, and he, with his unusually beautiful penmanship, featuring “letters soft and round like a caress,” begins his “poem…one which is poised to do what only the best poetry can: name what has never existed before and bring it to life.” And so, Georgina Hubner is born.

Weeks later, after many delays in the transport of their letter from Lima to Spain, Carlos and Jose are rewarded with a copy of the book and a return letter for “Georgina,” an occasion which results in great celebration among their fellow “poets” in Lima – and some controversy. Some say Jose and Carlos must answer the letter; other say not. Some want them to send a photograph of Georgina, others say that great poets do not deserve to be mocked and that Jose and Carlos must confess the truth immediately and put a stop to the joke. Jose, however, proclaims that they will respond, and the next day, armed with more rose-scented paper purchased for the occasion, he and Carlos begin their next letter to Jimenez.

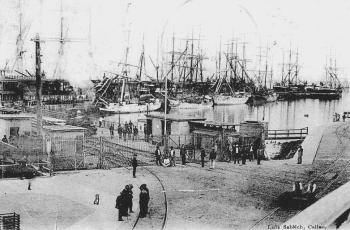

Taken in 1903, this photo shows the busy port of El Callao, just west of Lima, through which all the letters between Georgina and author Jimenez are sent.

Within this framework, in which a series of letters develops as the reader would expect, the author keeps the love story fresh and original, despite the deliberate and humorous clichés of the plot. Jose and Carlos, both extremely wealthy, represent different classes, since Jose is of old wealth and aristocracy, and Carlos is nouveau riche, and the two poets think of Georgina differently: For Jose, she is “merely a pretext, a means by which to fill his desk drawer with holy relics from the Maestro.” Carlos, on the other hand, “strives to give Georgina a personality and a biography.” Every afternoon, the poets repair to a dilapidated garret (owned by Carlos’s family), where they are “thrilled by the sensation of poverty, as they roam among the burlap sacks and heaps of dusty junk like the lucky survivors of a shipwreck.” There they work on the next letter and play the “character game,” in which they identify people they know and people they see from their window in terms of literary characters, an activity which causes the novel’s author Gomez Barcena to remark that this is fitting for characters like Jose and Carlos who see literature all around them and for whom everything that happens around them “happens just as they’ve read in books.”

Carlos, in his search for love, delivers elaborate dresses to a brothel and asks his favorite girl to model them. He wants her to look like an elegant woman from a painting by Joachim Sorolla, shown here.

Their friends, also romantic young poets, encourage them, talking about poetry and their inspiration for the future. Gradually, Jose and Carlos begin to see each other within the traditions of a novel – and ultimately as characters within that novel – and while they realize that they may never produce a perfect poem, they also believe that it may not matter. They may be destined to accomplish something even more important: the creation out of nothing of a great love celebrated by another poet, the life of Georgina as seen by the poet Jimenez. The comedy of Part I moves on to Part II, “A Love Story,” an epistolary novel, as Jose and Carlos meet with a local scrivener who helps them create the kind of characterization for Georgina which will attract Juan Ramon Jimenez through her letters. Soon, they decide to write a book about the poet himself, adding further to the layers of creation and which may become this novel itself.

A brothel painted by Toulouse- Lautrec shows a young woman in white, awaiting a customer, perhaps Carlos, who dresses his favorite partner as a lady and likes to imagine her as one. l

As the two poets continue writing, their interests change, with Jose and his friends continuing to produce Georgina’s increasingly erotic letters, while Carlos wants to learn more about real love, a task which takes him to the brothels of Lima and a relationship with a young woman there. The love story of Georgina and Jimenez becomes more complicated, and the levels of fiction and metafiction become more complex as the novel appears to conclude. Part IV, however, picks up the story fifteen years later when Carlos and Jose meet in an epilogue. There the reader discovers that the story of Georgina did not conclude as the two young poets and we, the readers, had assumed. One of the men, unnamed, has recently found a poetry collection by Jimenez, originally published in Spain in 1913 but never publicized because of World War I. That collection contains an astonishing work that one of the men says is “better than they themselves will ever be, that is worth more than their wives and children…more than their pasts and futures.” Suddenly, the former poet – and, ultimately, the reader – comes to a new recognition, stunned by the power of narrative and poetry to affect lives on many levels in a novel which started as fun and concludes in serious contemplation about writing and its power. I was totally taken aback by the conclusion, which adds many other layers to this novel and makes it both fun to read and hard-hitting at the same time.

ARC: Houghton Miffliin Harcourt

Photos, in order: The photo of author Juan Gomez Barcena appears in http://specimens-mag.com

Poet Juan Ramon Jimenez, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1956, is age twenty-three in 1904, when two university students from Lima “introduce” him to “Georgina,” who requests a copy of his latest book. http://peru.com/

The busy port of El Callao in 1903, just west of Lima, is shown on http://www.delcampe.net

Carlos Rodriguez, one of the young poets writing as Georgina, is desperate to learn what love really is, and he has a fetish in which he enjoys seeing a favorite prostitute at the local brothel dress up in a series of elaborate and romantic dresses like the ones worn in paintings by Joachim Sorolla, shown here: http://wiki.cultured.com/

When Carlos first sees the young prostitute wearing an elaborate dress he has brought her, “she has been transformed into “a figure from a Sorolla painting who has wandered out of her canvas and into a Toulouse-Lautrec brothel…It’s as if he were looking at the static image of a painting.” The brothel painting is found on https://en.wikipedia.org/