“There was a popular song at the time that people danced to. The hero was an old stewing hen no one wanted to eat at first but later everyone was fighting over. It was a song by Los Van Van called – “Stick him on the barbecue” – and I’m afraid we carried on dancing to it because…this song was the one place where we could not only find a chicken but actually eat one.”

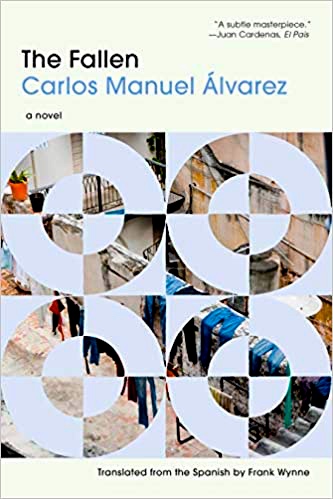

Set in contemporary Cuba, and focused on “ordinary” citizens trying to make ends meet so that they can enjoy their “freedoms” and their personal lives, author Carlos Manuel Álvarez writes his debut novel almost as if it were an opera. Intense and full of emotion, much of it kept hidden from the outside world, the novel features four main characters living their separate lives and sharing them with the reader throughout five different sections. The four characters appear in the same order in each of the sections – the Son, Mother, Father, and Daughter – giving the reader insights into their “solo” lives at the same time that their connections to the family become clear. Life in Cuba is difficult and often unpredictable, and though the foundation of the country is based on high ideals, the practicalities of staying alive in contemporary times sometimes depends on paring back the values and ideals and taking a less absolute approach. Author Álvarez, who divides his time between Cuba and Mexico, has actually lived through many of the difficulties which his fictional family describes here, giving the narrative a reality which is incontrovertible – and often sad. His characters believe in the country’s goals and ideals while recognizing that these don’t always work in day to day life, thanks to the behavior of some of the individuals wielding power in jobs and other hierarchies. The big dilemma is often one in which a person or family remains starving unless someone “borrows” one or two things secretly from their employer, allowing the person or family to survive at some minimal level. A character often has to make a choice between feeding the children or staying true to invisible national values which others ignore and watch their loved ones suffer terrible hunger.

Set in contemporary Cuba, and focused on “ordinary” citizens trying to make ends meet so that they can enjoy their “freedoms” and their personal lives, author Carlos Manuel Álvarez writes his debut novel almost as if it were an opera. Intense and full of emotion, much of it kept hidden from the outside world, the novel features four main characters living their separate lives and sharing them with the reader throughout five different sections. The four characters appear in the same order in each of the sections – the Son, Mother, Father, and Daughter – giving the reader insights into their “solo” lives at the same time that their connections to the family become clear. Life in Cuba is difficult and often unpredictable, and though the foundation of the country is based on high ideals, the practicalities of staying alive in contemporary times sometimes depends on paring back the values and ideals and taking a less absolute approach. Author Álvarez, who divides his time between Cuba and Mexico, has actually lived through many of the difficulties which his fictional family describes here, giving the narrative a reality which is incontrovertible – and often sad. His characters believe in the country’s goals and ideals while recognizing that these don’t always work in day to day life, thanks to the behavior of some of the individuals wielding power in jobs and other hierarchies. The big dilemma is often one in which a person or family remains starving unless someone “borrows” one or two things secretly from their employer, allowing the person or family to survive at some minimal level. A character often has to make a choice between feeding the children or staying true to invisible national values which others ignore and watch their loved ones suffer terrible hunger.

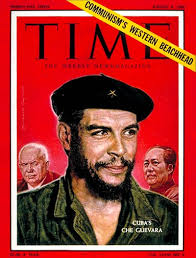

Diego, the first character, is the eighteen-year-old son of Armando, who is a committed revolutionary, “a die-hard Fidelista” distraught by the failures he sees all around him. Diego, who was drafted when he finished school at eighteen, has had a hard life. His “home” was so lacking in amenities that the family had to eat on the floor. When he came home from school at age eight or nine, there was nothing there – he had no roller skates, no birthday celebrations, no TV, no Nintendo, no chance to go to the beach, and, importantly, no bicycle – nothing to look forward to. Constantly presented with his father’s example of Che Guevara, who had a chance to get a free bicycle for his daughter but refused it because “bikes belong to the state,” Diego was expected to accept his circumstances and celebrate Che instead. When he became first in his class, he received no positive recognition and was bullied by other students. In the army, he always did what he was told, until he was viciously attacked by another man ten days before he was set to be released. When released, he returned home, feeling like an old man, having accomplished nothing and with nothing to look forward to.

His Mother’s story reveals that she is seriously ill, with seizures and strange dreams which make her feel as if she is “located somewhere outside her hand,” which seems to act independently of her. A former teacher, she is no longer able to work, and she is desperately lonely and conflicted. Her husband Armando has been working as the uncompromising manager of a hotel run by the Minister of Tourism, and he is always having problems with his assigned 1995 Nissan, which is constantly breaking down and uses more fuel than he is authorized to obtain. Armando believes that times are harder now than they were in the past. “The hardest times are those when no one wants to do anything, times marked by a crisis of values, a spiritual simple-mindedness, too little determination. The mechanics in the repair shop don’t want to work. They spend their days sitting in the cars, smoking, telling stories or talking about everything and nothing…They need a firm hand, the lot of them.” His own “Che Guevara” point of view is not working well, yet he still refuses to cooperate with a Party official when he is told to fire two people and appoint two of the official’s acquaintances, a big mistake professionally.

Maria, the Daughter, has given up her chance to go to university in order to work at the hotel, but has recently had to stop working there in order to return home to take care of her mother, who is now receiving strange phone calls. At this point, Maria introduces one of the most moving and empathetic characters in this book. René, who does not have his own section, appears occasionally throughout the latter part of the book, adding a great deal of emotion and creating a kind of personal identity with which readers will identify. Brought up by his neighbors because his mother had no choice but to work as a prostitute, he dropped out of school and began stealing, “developing a sixth sense for details.” When he recognizes that people in his area are becoming sick from the environmental consequences of the mining operations, he leaves and heads to work in the factories. At eighteen he has an accident which leaves him horribly disfigured, but he gathers up his courage and then heads back to work, this time as a driver. It is through this work that he comes to know Maria, the daughter of the family which features in this book. All benefit from the association with René, though questions arise about the source of some of his gifts and supplies. Ultimately, everyone “falls,” and the title of the book is confirmed. No one escapes disaster, and repeating imagery of chickens and their fights provides dramatic symbolism which brings the conclusion “home.”

Author Carlos Manuel Álvarez completes his work in fine style, his imagery cementing the themes and providing both life and death in the novel and in the lives of his characters. Like the operas to which I likened this novel in the opening paragraph, the closing sections converge with what resembles a series of arias culminating in a kind of Grand Chorus, and the inclusion of René as a damaged but oddly likable character adds immeasurably to the stories throughout regarding family love and personal independence. A serious literary novel with much to say about Cuba, its past and its present.

Photos. Che Guevara’s portrait on Time may be found here: https://time.com

The 1995 Nissan Sedan, which the Father borrows from his employer, is from https://row52.com

The chicken fight, which becomes symbolic here, appears on https://www.bhwt.org.uk

The author’s portrait may be found on https://www.miamibookfair.com