“Did you ever imagine having to go to prison? I mean, the way an employee imagines being fired or a doctor imagines contracting an illness? A professional risk? Or did you think you’d keep going and end up retiring as a terrorist, in the old terrorists’ home, where young terrorists would look after you?”–Old acquaintance, questioning a newly released terrorist.

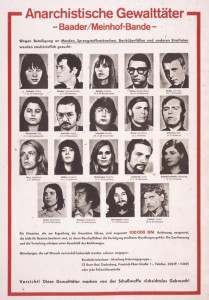

Bernhard S chlink faces a monumental challenge in this novel in which he attempts to connect the terrorism of the Red Army Faction (represented by the Baader-Meinhof Gang in Germany in the seventies) with the earlier German national terrorism that the Nazis represented and the contemporary terrorism of Al-Qaeda. Here he investigates what makes people become terrorists and what happens to them in the aftermath of their crimes. At one point Schlink even has a character question whether Germany is the victim of a curse: “Isn’t it a curse, what’s being passed on from the [World War II] generation before Jorg [a Baader-Meinhof member who killed four people] to Jorg, and from Jorg to his son?… We still have witches and fairies, and there are curses that are sometimes lifted from us only after generations.”

chlink faces a monumental challenge in this novel in which he attempts to connect the terrorism of the Red Army Faction (represented by the Baader-Meinhof Gang in Germany in the seventies) with the earlier German national terrorism that the Nazis represented and the contemporary terrorism of Al-Qaeda. Here he investigates what makes people become terrorists and what happens to them in the aftermath of their crimes. At one point Schlink even has a character question whether Germany is the victim of a curse: “Isn’t it a curse, what’s being passed on from the [World War II] generation before Jorg [a Baader-Meinhof member who killed four people] to Jorg, and from Jorg to his son?… We still have witches and fairies, and there are curses that are sometimes lifted from us only after generations.”

This tendency to avoid looking at the real issues, as illustrated by this quotation, unfortunately pervades this novel which had the potential to cast real light on terrorism and the myriad ways it affects not only society and its victims but also the terrorists who have committed crimes, including murder, in the name of improving society.

Set in the present, the novel opens with Christiane, the physician sister of Jorg, a man who has been imprisoned for twenty-four years for his crimes in the 1980s, waiting outside the prison from which he is to be released. She has planned a weekend at the dilapidated but spacious old estate she and a friend have purchased in Brandenberg, a place surrounded by parkland and fields, with a stream and sense of quietude that everyday life does not often offer. She has invited several of Jorg’s former friends to join them for the weekend, before the press and the country can intrude on their privacy, and she has high hopes of providing Jorg with an environment in which he can let down and begin to come to terms with his past and his long imprisonment. Of the people who visit for the weekend, all have been supporters of the RAF movement in the past, but none, other than Jorg, have participated in the sometimes deadly actions taken by the group in the belief that they are making positive changes for the country. Significantly, all have established new lives, and none are currently involved in any radical causes.

The action , as it evolves, is psychological action, primarily, and a sense of ominous prescience, as characters interact, is reminiscent of some of Agatha Christie’s “closed room” mysteries. Everyone wants answers to questions, but no one is sure what to ask or how to evaluate the answers. Jorg, the “hero” of the eighties, is a weakened man who is out of touch with present-day life, having little idea of the major changes that have occurred politically during the twenty-four years that he has been incarcerated. As the weekend guests connect and reconnect with each other, and former loves and former relationships are recalled and sometimes rekindled, the reader is left hoping that the author will get the novel out of the personal and into the universal which will give meaning to their actions.

, as it evolves, is psychological action, primarily, and a sense of ominous prescience, as characters interact, is reminiscent of some of Agatha Christie’s “closed room” mysteries. Everyone wants answers to questions, but no one is sure what to ask or how to evaluate the answers. Jorg, the “hero” of the eighties, is a weakened man who is out of touch with present-day life, having little idea of the major changes that have occurred politically during the twenty-four years that he has been incarcerated. As the weekend guests connect and reconnect with each other, and former loves and former relationships are recalled and sometimes rekindled, the reader is left hoping that the author will get the novel out of the personal and into the universal which will give meaning to their actions.

The author frequently reminds the reader of the continuing terrorism of Al-Qaeda (with which one guest wants to connect his current anti-government organization), and two scenes in the book are set in the World Trade Center during the September 11 attack. One takes place at the Windows of the World Restaurant, and one takes place on a lower floor after a plane crashes into the building and sets it on fire. Considering the enormous difference in scale between the 9/11 attack and the events of from Jorg’s past, I was personally offended by the connections Schlink made between the Baader-Meinhof crimes, however terrible, with the single worst act of terrorism in world history. Linking them seemed opportunistic, a way to draw on the horrors of 9/11 in order to add emotionalism to the impact of the novel.

The novel could have been a thorough and thoughtful analysis of Germany between World War II and the present, with an even more thorough analysis of the philosophical and political issues also involved. Between the passage in which a character blames the problems of German terrorism on some mystical curse and the author’s later attempts to link the attacks on the World Trade Center to the historical issues in Germany between the Nazis and the present, however, I found that I lost my interest in these characters and their fictional problems. Schlink is a talented writer with a unique gift for conveying descriptions, especially lyrical ones, but this novel, which promised so much, was ultimately a disappointment.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from www.moviepilot.de

The photo of the old house in Brandenburg, surrounded by a park-like setting, is from http://img175.imageshack.us

The Wanted poster for the Baader-Meinhof Gang is from http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org.