Note: Justin Cartwright has been WINNER of the Commonwealth Writers Prize, the Whitbread Award, and the Hawthornden Prize.

“His father never grasped the idea that great wealth corrupts. Or tends to corruption. His father regarded his wealth as confirmation of his unique qualities which selective breeding of the privileged had produced. It is the updated version of the Victorian idea that the English gentleman was the outcome…of years of evolution, fostered by rugby, cold showers, beating, poor food, and study of the classics.”

Julian Trevelyan-Tubal, the second son of Sir Harry, is now the eleventh generation of Tubals to have run the family’s bank, an old and prestigious institution which has now, not surprisingly, fallen victim to the same deteriorating economic forces as every other bank and investment company in London and around the world. With Sir Harry in Antibes, where he is recuperating from a stroke, which has left his speech impaired, Julian has been responsible for managing the “firm.” His older brother Simon had, after the death of their mother, rejected most of his family, along with his obvious role in the company, by traveling the world—“the hippy Tubal or the hairy heir.” It was left to Julian to keep the business all together, though “It is not so easy to be born rich in a world where everything that surrounds you from birth is old and beautiful and patinated, a world where you are steered, like it or not, towards the family business.” Julian’s role as heir apparent is even more complicated than usual, since his father “never

Julian Trevelyan-Tubal, the second son of Sir Harry, is now the eleventh generation of Tubals to have run the family’s bank, an old and prestigious institution which has now, not surprisingly, fallen victim to the same deteriorating economic forces as every other bank and investment company in London and around the world. With Sir Harry in Antibes, where he is recuperating from a stroke, which has left his speech impaired, Julian has been responsible for managing the “firm.” His older brother Simon had, after the death of their mother, rejected most of his family, along with his obvious role in the company, by traveling the world—“the hippy Tubal or the hairy heir.” It was left to Julian to keep the business all together, though “It is not so easy to be born rich in a world where everything that surrounds you from birth is old and beautiful and patinated, a world where you are steered, like it or not, towards the family business.” Julian’s role as heir apparent is even more complicated than usual, since his father “never understood that to produce a decent return you need financial instruments that banks of deposit never dreamed of. The cosy world, in which, for example, undisclosed assets could be left undeclared and untaxed, had changed for ever.”

understood that to produce a decent return you need financial instruments that banks of deposit never dreamed of. The cosy world, in which, for example, undisclosed assets could be left undeclared and untaxed, had changed for ever.”

Julian has quickly discovered how tenuous the bank’s position has become during the current economic crisis. Wanting to accept an offer to sell the bank to an American, Cy Mannheim, Julian has found it necessary to borrow two hundred fifty million pounds from the family trust for a limited time to shore up the bank, which now has eight hundred million pounds worth of toxic assets and useless mortgages in territories the bank has never even visited. Fortress Lion, their hedge fund has been a disaster. Donations to family charitable trusts have ceased, as have payouts, and even Sir Harry’s beloved yacht is about to be sold to a Russian plutocrat.

All Hallows, the oldest church in England, where Sir Harry's funeral takes place. It has no Chagall windows.

Justin Cartwright, an award-winning author who was born and grew up in South Africa and now lives in London, uses his dry wit and sense of satire to tell the story of the Tubals, a family which has few inner resources to deal with the crisis the bank is facing: “The money simply imploded. It no longer exists. Nobody can explain it.” Caught between wanting to get out from under the problems of the bank and wanting to preserve the family’s prestige and sterling social reputation, Julian is frantic. He is aware that he is not very different from Leeson, Enron, and Lehman Brothers, “who tried to hide their debts with ‘Repo 125,’ ” and he knows that he MUST repay or he will be going the way of the crooks: Nicholas Leeson, a derivatives broker, caused the collapse of Barings Bank, the UK’s oldest investment bank, and went to prison. Jeffrey Skilling, at Enron, showed how it was possible to hide billions in debt from accountants and regulators—before the company went bankrupt. He was sentenced to more than twenty-four years in prison. Kenneth Lay, his boss, might have served up to thirty years in prison, but died shortly before his trial. Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy was the biggest bankruptcy of an investment bank in all U.S. history. Julian Trevelyan-Tubal fears that he, himself, may soon be considered among these names of shame, though he believes he has not done anything legally wrong in his effort to keep the bank afloat long enough to sell it.

Chagall Window from All Saints in Tudely

Adding to the drama of the financial crisis are stories involving people from Julian’s family. Artair MacLeod, formerly married to Fleur, Sir Harry’s much younger wife, has been given a monthly stipend for life, a payoff to last as long has he never discusses his relationship with Fleur. When Artair, who is working on a long play about Irish author Flann O’Brien, does not receive his allotment for more than two months, he begins to investigate, and he seeks help from a young newspaper person in Cornwall. He needs financial support long enough that he can get Daniel Day-Lewis to agree to perform in the production he imagines of Flann O’Brien’s work. Sir Harry’s long-time assistant, Estelle, a homely woman who was totally in love with Sir Harry, is willing to do anything to protect him and the family reputation. And Cy Mannheim, who wants to buy the bank, asks for more complete financial data. In the meantime, news leaks about the Tubals appear slowly in the local Cornwall paper, on-line, and eventually in the national newspapers.

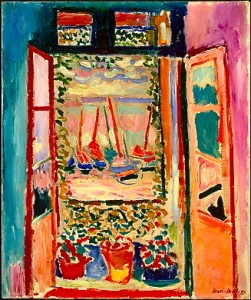

Matisse's "Open Window at Collioure," given by Sir Harry to Estelle

Cartwright is a straightforward, no-nonsense author, who employs his dry wit and sense of irony to create scenarios easy for the reader to identify with and participate in. Julian is a reluctant CEO, and most readers will feel empathy for him as he tries to extricate himself from a job he neither sought nor wanted, and will understand his desire to preserve the family’s reputation for integrity. As the complications work toward their conclusions, the interrelationships between the financial institutions, the governing bodies for these institutions, and the press, the most important source of information for the public, are laid bare.

The global economy and the interrelationships between the companies in one country and customers, investors, and potential buyers in another become even more at issue. In the conclusion, Cartwright provides a final chapter, in which he says, “There are beginnings and there are ends, and there are also many ways of telling the same story.”

Monte Sainte Victoire by Cezanne, one of Sir Harry's favorite paintings

He brings the reader up to date through the conclusion, connecting all the characters and telling how they have coped with the inevitable conclusion regarding the Tubal bank. Ultimately, “People talk about true stories. As if there could possibly be true stories; events take place one way and we recount them the opposite way.” Cartwright reconciles the questions involving the main characters, but he leaves many other questions up in the air.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.dailymail.co.uk.

All Hallows, the oldest church in England, where Sir Harry’s funeral takes place, is seen here: http://www.virtual-london.com. It does not contain any Chagall windows, as described in the book, but All Saints in Tudely does, as seen in the next photo: www.tudeley.org

Matisse’s “Open Window at Collioure,” given by Sir Harry to Estelle, is now in the National Gallery of Art. http://en.wikipedia.org

Cezanne painted appro ximately sixty pictures of Mont Sainte Victoire, which he saw from his house. Sir Harry was credited with owning three Cezannes, one of which, a special favorite, was of Monte Sainte Victoire: http://www.artchive.com That painting is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

ximately sixty pictures of Mont Sainte Victoire, which he saw from his house. Sir Harry was credited with owning three Cezannes, one of which, a special favorite, was of Monte Sainte Victoire: http://www.artchive.com That painting is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The final photo is of Flann O’Brien, author of At Swim, Two Birds, the subject of Artair MacLeod’s play, which he hopes will star Daniel Day-Lewis.