“She is no longer frustrated to have lost a sense, the appeal of which she has forgotten. What is sight, exactly? To know what everyday objects look like? A table, a chair, a mirror? But she knows [what they look like] better than anyone, in her own way, and this way suits her….With time, she has persuaded herself that sight is an illusion that leads the other senses astray, renders them ineffective. Whereas hers are always alert.”

When three-year-old Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759 – 1824) goes suddenly and completely blind one night as she sleeps, there is no dearth of physicians willing to treat her. Empress Maria Theresia of Austria immediately provides all the resources of the court – and of her court physicians. The child’s father, Joseph Anton von Paradis, is Her Majesty’s Secretary and has named his only child for the Empress. By the time the child is a teenager, she is a piano prodigy, and still blind, though she has already undergone years of medical experiments, all unsuccessful, painful, and often traumatizing. By age seventeen, Maria Theresia, only three years younger than her friend Mozart (who reportedly created his Concerto #18 in B Flat for her), has grown accustomed to her blindness. Not wanting to endure any more physical and mental torment to correct a condition which she does not regard as a problem, she secures her father’s promise to end all further treatments and experimentation.

When three-year-old Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759 – 1824) goes suddenly and completely blind one night as she sleeps, there is no dearth of physicians willing to treat her. Empress Maria Theresia of Austria immediately provides all the resources of the court – and of her court physicians. The child’s father, Joseph Anton von Paradis, is Her Majesty’s Secretary and has named his only child for the Empress. By the time the child is a teenager, she is a piano prodigy, and still blind, though she has already undergone years of medical experiments, all unsuccessful, painful, and often traumatizing. By age seventeen, Maria Theresia, only three years younger than her friend Mozart (who reportedly created his Concerto #18 in B Flat for her), has grown accustomed to her blindness. Not wanting to endure any more physical and mental torment to correct a condition which she does not regard as a problem, she secures her father’s promise to end all further treatments and experimentation.

French author/journalist Michele Halberstadt creates an intriguing study of Maria Theresia, whose blindness has been diagnosed by court physicians as amaurosis, a form of blindness “that appears suddenly without any malfunctioning of the optical system. Its onset is either toxic, congenital, or nervous.” Certainly there is a chance that this is a kind of hysterical blindness, caused by some trauma, perhaps within her family, but Sigmund Freud and his theories are still a hundred years in the future, and there appears to be no way, at that time, to discover what it is that is blocking her sight. Receiving an annuity from the Empress, Maria Theresia is able to live comfortably, study the piano (she eventually learns over sixty concertos by heart), perform in concert, and compose new works.

When Maria Theresia is eighteen, Franz Anton Mesmer, meets her father. Mesmer, married to a very wealthy widow whose husband had been the Secretary of Finance for the Empire, is an urbane and charming man who lives on an enormous estate in Vienna, “a small Versailles on the Danube” and the hub of Viennese intellectual and cultural life. Mesmer has been devoting himself, in recent years, to the study of medicine, under Prof. Stoerk, the Empress’s private physician, though he has already received his doctorates in theology, philosophy, and law. Fascinated by the case of Maria Theresia, he is interested in exploring the use of “magnetic healing” on her. The only problem is that her father has promised Maria Theresia he will not to pursue any more treatments. The idea for the treatments will have to come from Maria Theresia herself. Knowing that she must get out from under her father’s complete domination of her, she finally accepts Mesmer’s invitation to come to his estate where he operates a clinic, though she will stay for a few weeks in the house while the four or five other patients will stay in a different building.

It is at this point that the author stops “telling about” the life of Maria Theresia from known facts, as a journalist or researcher would, and, instead, finally “shows” the action, recreating the sexual coming-of-age of Maria Theresia inside the home of the forty-three-year-old Franz Anton Mesmer, whose wife is away traveling. As she is treated with his hands-on magnetic healing, she responds miraculously, not only to the treatment for her blindness but to Mesmer himself.

It is at this point that the author stops “telling about” the life of Maria Theresia from known facts, as a journalist or researcher would, and, instead, finally “shows” the action, recreating the sexual coming-of-age of Maria Theresia inside the home of the forty-three-year-old Franz Anton Mesmer, whose wife is away traveling. As she is treated with his hands-on magnetic healing, she responds miraculously, not only to the treatment for her blindness but to Mesmer himself.

Here the novel, unfortunately, becomes less a biography and more of a romance, filled with romantic clichés, both in description and in action. “Have faith in me,” Mesmer says, as the treatment continues. Soon she is “less in a rush to get better than she was eager to be with him,” because “No man had ever awakened her senses in this fashion.” She believes that “he is interested in the person she really is.” And he, of course, “felt the passion pulsing through him.” The “dazzling” seduction is described in the cringe-producing language of a modern romance novel.

What makes the novel interesting is not the possible love story between Maria Theresia and Franz Mesmer. It is the imagined response of Maria Theresia as she begins to see. Most of us, I think, would regard the restoration of the sense of sight as a miraculous and wonderful experience, yet Maria Theresia finds that it so changes all aspects of her life, especially her piano playing, that she is frantic about how to handle a future with sight. She can suddenly see her hands moving when she plays the piano, and finds that so distracting that she cannot concentrate on the music itself. She also becomes so dependent on Mesmer as her savior, during her recovery, that she cannot imagine leaving him for a career. “Music has ceased being my dream world,” she notes, yet she has no other world to take its place. Her parents find her new independence alarming, and Mesmer, who created the problem in the first place, suddenly recoils from the possibly career-ending rumors swirling at court.

For those who have never heard of Maria Theresia von Paradis, this is a fascinating story, despite the romantic clichés involved in the imagined love scenes. As the author continues the stories of Maria Theresia and Franz Mesmer up to their deaths, one can only wonder how much truth there might have been to the love story described here. Lacking a trove of letters and documentation, no one can ever know for sure the real reasons for the sudden ending of Mesmer’s treatments, and whether his magnetic healing might have led to further medical and psychological discoveries if they had continued. A good summer read for those interested in music and in pre-Freudian treatments for emotional disorders.

For those who have never heard of Maria Theresia von Paradis, this is a fascinating story, despite the romantic clichés involved in the imagined love scenes. As the author continues the stories of Maria Theresia and Franz Mesmer up to their deaths, one can only wonder how much truth there might have been to the love story described here. Lacking a trove of letters and documentation, no one can ever know for sure the real reasons for the sudden ending of Mesmer’s treatments, and whether his magnetic healing might have led to further medical and psychological discoveries if they had continued. A good summer read for those interested in music and in pre-Freudian treatments for emotional disorders.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://rentree-litteraire.com.

The pianist’s hands are by Ricardo DeAratanha, http://www.latimes.com

The only known portrait of Maria Theresia von Paradis appears on http://en.wikipedia.org . Another portrait widely reproduced and said to be of Maria Theresia, showing a performer in a state of partial undress and holding a viola da gamba, is from the previous century and is of composer Barbara Strozzi, according to researchers.

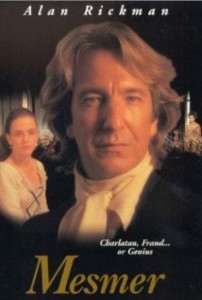

The poster is for a 1994 film directed by Roger Spottiswoode. Alan Rickman won the Award for Best Actor at the World Film Festival, Montreal, for his role as Mesmer.