“He felt it coming, the collapse…[but] his thoughts were clear as the weakness drained his body, and in that clarity he thought, absurdly, that this must be what it felt like to freeze to death or to have a stone crush the breath out of your body. The comparison made him wince despite his anxiety: see what melodrama tiredness can induce?” – thoughts of Abbas during his illness.

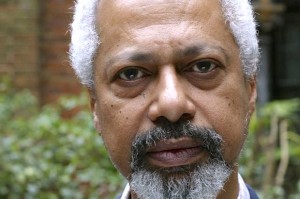

Abdulrazak Gurnah, born in Zanzibar and now teaching writing in England, has often focused during his writing career on the many issues of immigration – the difficulties of immigrants in adjusting to a new culture, the guilt sometimes felt about the family and culture left behind, and, ultimately, the confusion about what “home” means and the sometimes painful, almost physical, yearning for it. His novels, which have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, the Whitbread (now Costa) Award, the Commonwealth Writers Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book of the Year Award, have been thoughtfully written, with settings in Zanzibar, the Tanzania mainland, Kenya, and England (from the point of view of the immigrant), but it is this novel, The Last Gift, which may finally bring him the greater recognition he deserves.

Abdulrazak Gurnah, born in Zanzibar and now teaching writing in England, has often focused during his writing career on the many issues of immigration – the difficulties of immigrants in adjusting to a new culture, the guilt sometimes felt about the family and culture left behind, and, ultimately, the confusion about what “home” means and the sometimes painful, almost physical, yearning for it. His novels, which have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, the Whitbread (now Costa) Award, the Commonwealth Writers Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book of the Year Award, have been thoughtfully written, with settings in Zanzibar, the Tanzania mainland, Kenya, and England (from the point of view of the immigrant), but it is this novel, The Last Gift, which may finally bring him the greater recognition he deserves.

The most detailed and complex novel he has written on the subjects of immigration and displacement so far, The Last Gift is a multigenerational novel which opens with Abbas, a sixty-three-year-old man whose origins are, at first, unknown, returning to his residence in England after work. A conscientious, driven man, he is also very private, keeping to himself and not sharing his past even with his family. He becomes ill on the way home one extremely cold day, so ill that this proud man “wishes for someone to pick him up and carry him home.” On the bus he “watches himself from beside himself,” and when he finally arrives at his own bus stop, he is not sure if he will survive the walk home. Eventually, forcing himself to walk slowly and refusing to ask anyone for help, he arrives at his house, teeth chattering, heavily sweating in the cold, and only semi-conscious. Collapsing, he is taken to the hospital, where, worried, in pain, and thinking he might die, he realizes “that he had left things for too long, as he had known for so many years. There was so much he should have said, but he had allowed the silence to set until it became immovable.” He regards himself as a “sinful traveller fallen ill in a strange land, after a life as useless as a life could be.”

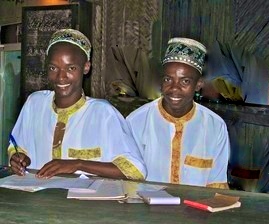

A school perhaps similar to the one Abbas attended – the first person in his family to do so. Photo from the Tanzania-Zanzibar International Volunteer Association, Facebook page.

Hanna, the daughter of Abbas and his wife Maryam, now calls herself Anna and works as a teacher, while their son Jamal is working on a doctorate tracing migration patterns from Africa and Asia into England. Jamal never quite believes in the story of his mother as a foundling, and he has the feeling, regarding his father, that “There was something to be ashamed of, something that had been with him most of his life.” Anna declares that “They are lost…Ba deliberately lost himself a long time ago, and Ma found herself lost from the beginning…What I want from them is a story that has a beginning, that is tolerable and open.” Both children have failed to put down roots, though they are British citizens.

Two young men from Zanzibar wear the traditional kanzu shirt and kofia head covering which Abbas mentions.

The memories which Abbas has hidden for so many years continue to torment him as he begins to recover from two strokes, from which he must regain his ability to speak, and it is not until well into the novel that his own story emerges. In the meantime, the stories of his wife Maryam, his children Hanna (Anna) and Jamal, and their relationships with each other unfold in detail. Maryam, forty-seven when Abbas becomes ill, knows little about her own family. Left as a foundling outside a hospital in Exeter, Maryam was only three or four days old when she entered foster care. Her loving foster parents wanted to adopt her but were declared too old, and she was taken away at age three, only to be fostered by several other families before finding relative stability with a “mixed” family in which the woman, a nurse from a Muslim family in Mauritius, and the man, an electrician from a Hindu family from India, try to give Maryam a sense of stability and an understanding of what family means. The irony of a British foundling being brought up by immigrants gives additional poignancy to the novel’s themes.

Two women walk down the street in Zanzibar, one wearing western dress and one wearing the buibui, the full covering now preferred by many Muslims in Zanzibar. Abbas’s first love wore the buibui.

The points of view shift among these four characters as Maryam continues to deal with Abbas’s illness and resumes her work at a hospital, and Abbas relearns how to speak and tries to work himself up to telling, finally, the secrets that he has kept hidden for thirty years. Both parents reminisce about their childhoods and about the events which separately drove each of them to run away from the families in which they were living. The love affairs of the children, Anna and Jamal, and their changes of cities, apartments, and houses (possibly looking for the symbolic “perfect home”) dominate much of the middle of the novel, and it is only when the children finally discover the terrible secret which Abbas has withheld that they are ready to begin to come to terms with who their parents are and, as a result, who they themselves are and where they belong.

Abbas’s early life in Zanzibar looms over and dominates the novel, even though it is a relatively short part of the narrative, and the author, while describing Abbas’s life in memorable detail from the time Abbas was a child, branches out in many different directions as he develops his themes of alienation, displacement, escape, guilt, hope, and eventually resolution among the generations. The reader eventually comes to know Abbas’s parents and his brother and sister; Maryam’s life with her various foster parents; the family of Anna’s lover and their attitudes toward immigrants; Jamal’s discovery of cross-cultural love; and even ingrained post-colonial attitudes which the characters discover among the British citizens with whom they interact.

Occasionally, the novel becomes melodramatic, and in a few cases, even predictable, as the author attempts to illustrate every conceivable aspect of the immigrant experience, a goal which sometimes leads to too much detail about peripheral characters, some of whom might have been eliminated without losing focus. Still, the novel fascinates, in part because it is so much more complex in its goals and structure than Gurnah’s previous novels have been. As I read, I could not help but think that the author himself was deliberately summing up the threads and themes of his previous novels, writing this one as his grand statement.

ALSO by Abdulrazak Gurnah: BY THE SEA, DESERTION, PARADISE, GRAVEL HEART

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears in http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/

The photo of a school in Zanzibar is posted on the Facebook page for the Tanzania-Zanzibar International Volunteer Association . TZIVA is a small volunteer organization providing technical, educational, and hands-on volunteer support to grassroots community projects on the island of Zanzibar, Tanzania. For additional information see http://www.tziva.org/

The picture of the kanzu (shirt) and kofia (head covering), traditional dress for men in Zanzibar, comes from http://www.malcolmkirktravels.net/

The photo of the two women, one wearing the full-covering buibui, was posted on http://www.mambomagazine.com by Jaki Sainsbury

The map of Zanzibar/Tanzania appears on http://www.worldatlas.com/

ARC: Bloomsbury