Note: This novel, published in Australia as Diamond Dove, was WINNER of the Ned Kelly Award for Best Novel in 2007.

“Boys brawling over a flaccid football, girls bouncing a basketball in a cloud of dust, young men working on a car, pensioners chewing on the cud. A bare-arsed tacker raced past pushing a pram wheel with a length of wire….The Moonlight Downs community.”

Part white and part aborigine, Emily Tempest has always had “a foot in both camps.” As a child living with the aborigines at Moonlight Downs in the Australian Outback, while her white father worked at the Moonlight cattle station, Emily was a happy member of the community until she was fourteen, when her natural curiosity and tempestuous nature led her to violate a strong community taboo. Immediately, she was sent off to boarding school in Adelaide, her best friend, and partner in the violation, facing a worse penalty within the community.

After attending college, where she started three degrees (including law) and finished none, “I headed off overseas,” she says. “Deckhanded on a yacht across North Africa. Ran a bar in Turkey. Travelled through Rajasthan – on a bloody camel, half the time. Spent six months wandering along the silk Road itself. I w as running so hard it never occurred to me that I was lost.” Eventually, however, she finds her way back “home” to Moonlight Downs for the first time in twelve years, just as Lincoln Flinders, the father of her best friend and the leader of the community, is found murdered. There is no dearth of motives.

as running so hard it never occurred to me that I was lost.” Eventually, however, she finds her way back “home” to Moonlight Downs for the first time in twelve years, just as Lincoln Flinders, the father of her best friend and the leader of the community, is found murdered. There is no dearth of motives.

The aborigine community has recently had its rights to ancestral lands upheld by the Australian courts after whites had appropriated it for cattle grazing and development. Now, resentful whites have been trying to buy or lease it back. Racial tensions and cultural conflicts underlie whatever relationships exist between the whites and the “blacks,” and some of the aborigines’ most sacred sites have been deliberately destroyed by whites. Aborigine youth who have lived in Bluebush, the nearest community, no longer feel the ties to the land that their parents and ancestors have had, and the community’s future is threatened. “Rust was seeping into the soul of the community,” Emily observes. Determined to find out who murdered Lincoln Flinders, she is in a unique position to do so, but she also has her own enemies, both inside and outside the aborigine community.

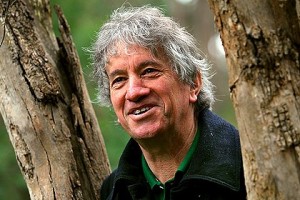

Australian author Adrian Hy land, who won the Ned Kelly Award for this atmospheric and dramatic first novel, creates a narrative that moves at warp speed, filled with action and excitement. At the same time, he also invites contemplation of the natural world and the lives of the aborigines who identify with nature on a visceral, even mystical, level. Their needs are basic, their lives are not pretty, and their land is infertile, making their ability to be happy because of their culture and beliefs significant by contrast.

land, who won the Ned Kelly Award for this atmospheric and dramatic first novel, creates a narrative that moves at warp speed, filled with action and excitement. At the same time, he also invites contemplation of the natural world and the lives of the aborigines who identify with nature on a visceral, even mystical, level. Their needs are basic, their lives are not pretty, and their land is infertile, making their ability to be happy because of their culture and beliefs significant by contrast.

Hyland’s dialogue is earthy, filled with aborigine and white slang (for which there is a glossary in the front), and he is often profane, preferring to show his characters and their lives as they really are, instead of the way an “overcivilized” reader might wish them to be. H is remarkable ability to recreate the seemingly bleak North Australian landscape and the people who consider it “home” puts the reader in touch with life’s most basic needs and the aborigine culture which has developed there. Despite its movie script ending, this is an unusual and captivating mystery, one that sticks in the memory long after the book ends.

is remarkable ability to recreate the seemingly bleak North Australian landscape and the people who consider it “home” puts the reader in touch with life’s most basic needs and the aborigine culture which has developed there. Despite its movie script ending, this is an unusual and captivating mystery, one that sticks in the memory long after the book ends.

ALSO by Hyland: GUNSHOT ROAD

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.smh.com.au.

The author has said that he has modeled the town of Bluebush on both Alice Springs and Tennant Creek, The bleak landscape of Alice Springs is seen here: http://members.virtualtourist.com

In the bottom photo, Dianne Stokes, an elder of the Yapa Yapa clan, and her daughter, Sky in Muckaty, are among the clan members opposed to a 2007 plan which would put a nuclear dump in the Outback and require transit of materials through their ancestral lands. “if it is so safe, why don’t they put it in Sydney?” she asks. http://www.smh.com.au