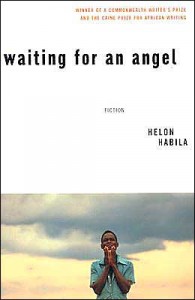

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for First Novel in 2004. The author has won additional prizes for his novels since then.

“There was nothing to believe in: the only mission the military rulers had was systematically to loot the national treasury; their only morality was a vicious survivalist agenda in which any hint of disloyalty was ruthlessly crushed.”

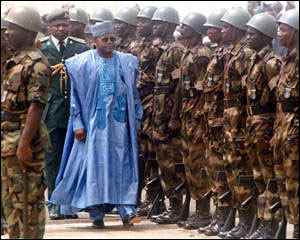

Nigeria in the 1990s, the setting for this novel, was a police state of such sadistic violence, with human rights abuses so staggering, that the country was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations, and virtually every other country had sanctions against it. Every hint of dissent and every suspicion of democratic thinking by many of the country’s most gifted writers and thinkers were wiped out by the military government of Sani Abacha. Focusing primarily on Lomba, a journalist and frustrated novelist, who, in the opening chapter is a starving political prisoner in a Lagos jail, author Helon Habila jumps back and forth in time, introducing us in succeeding chapters to the lives of ordinary citizens of Lagos, men and women, including Lomba himself, living on Poverty Street, trying to maintain some semblance of hope in an increasingly hopeless world. Lomba, jailed for two years without a trial as the novel opens, has gone beyond anger, which he describes as “the baffled prisoner’s attempt to re-crystallize his slowly dissolving self,” and entered “a state of tranquil acceptance” of his fate. When the jailer finds the poems and journal entries he has written and hidden, he persuades Lomba to write some love poems for the better-educated woman he is courting. A brief ray of hope flickers when the woman recognizes Lomba’s cryptic messages and comes to the prison to meet him.

Nigeria in the 1990s, the setting for this novel, was a police state of such sadistic violence, with human rights abuses so staggering, that the country was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations, and virtually every other country had sanctions against it. Every hint of dissent and every suspicion of democratic thinking by many of the country’s most gifted writers and thinkers were wiped out by the military government of Sani Abacha. Focusing primarily on Lomba, a journalist and frustrated novelist, who, in the opening chapter is a starving political prisoner in a Lagos jail, author Helon Habila jumps back and forth in time, introducing us in succeeding chapters to the lives of ordinary citizens of Lagos, men and women, including Lomba himself, living on Poverty Street, trying to maintain some semblance of hope in an increasingly hopeless world. Lomba, jailed for two years without a trial as the novel opens, has gone beyond anger, which he describes as “the baffled prisoner’s attempt to re-crystallize his slowly dissolving self,” and entered “a state of tranquil acceptance” of his fate. When the jailer finds the poems and journal entries he has written and hidden, he persuades Lomba to write some love poems for the better-educated woman he is courting. A brief ray of hope flickers when the woman recognizes Lomba’s cryptic messages and comes to the prison to meet him.

The novel then flashes back to the years before Lomba’s arrest, and as various episodes unfold, the author shows us the effects of this dictatorial government on the ordinary people who populate the country. Though life is difficult and opportunities almost non-existent, the young people still have hopes and dreams. When Lomba and a friend have their fortunes told by a poet, one of the young men asks to know the day of his death, which he hopes will be “spectacular and momentous,” a day he is assured he will know when the time comes—and does. A second friend, whose parents have been killed in a car crash, is so grief-stricken that he makes an intemperate and idealistic speech, then is arrested, severely beaten, and driven insane. With no chance of getting his own novel published, Lomba himself takes a job writing for the Dial, for which he occasionally reports on political demonstrations, one of them a demonstration in which people peacefully protest the neglect of their neighborhood. “We are dying from lack of hope,” his friend Joshua says at the demonstration. The unarmed protesters are suddenly attacked by fifty armed riot police, tear gas is exploded, protesters are severely beaten, and running women and children are killed by cars speeding on the adjacent highway.

The novel then flashes back to the years before Lomba’s arrest, and as various episodes unfold, the author shows us the effects of this dictatorial government on the ordinary people who populate the country. Though life is difficult and opportunities almost non-existent, the young people still have hopes and dreams. When Lomba and a friend have their fortunes told by a poet, one of the young men asks to know the day of his death, which he hopes will be “spectacular and momentous,” a day he is assured he will know when the time comes—and does. A second friend, whose parents have been killed in a car crash, is so grief-stricken that he makes an intemperate and idealistic speech, then is arrested, severely beaten, and driven insane. With no chance of getting his own novel published, Lomba himself takes a job writing for the Dial, for which he occasionally reports on political demonstrations, one of them a demonstration in which people peacefully protest the neglect of their neighborhood. “We are dying from lack of hope,” his friend Joshua says at the demonstration. The unarmed protesters are suddenly attacked by fifty armed riot police, tear gas is exploded, protesters are severely beaten, and running women and children are killed by cars speeding on the adjacent highway.

Strongman Sani Abacha inspects his troops

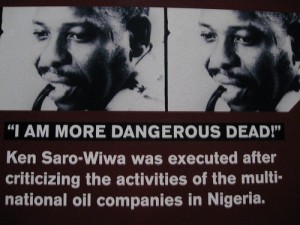

Because the author presents these episodes in random order, depicting the families, everyday life, and hopes and dreams of the participants, the reader easily imagines what life must have been like during this time and can envision what his/her own life might have been under the same circumstances. But Habila adds further reality to his depictions of life in Nigeria under Sani Abacha by including some well-known historical events and their effects on Lomba and the fictional characters: the hanging of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the killing of Dele Giwa, the editor of Newswatch magazine, by a letter bomb, and the shooting of the wife of Abiola, the opponent of Abacha who was jailed simply for challenging him.

Mrs. Kudirat Abiola, senior wife of an Abacha opponent, was murdered on the streets of Lagos following her husband’s election win

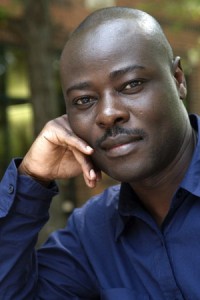

In one of the most telling episodes in the novel, Lomba goes to a party and meets the writers and poets of Lagos. A man introduces himself to him, saying, “Hi, I am Helon Habila.” Suddenly, the reader realizes how much of this novel may be autobiographical, a factor which makes the drama of the story even more intense. We know from the author’s biography that he once held the same job as Lomba and that he is now living in London. What we do not know is how many of the other realistically presented events may also be true. The reader may wonder how he knows so much about life under sadistic jailers in the prisons of Lagos, though no one will doubt the accuracy of his descriptions.

Because the chronological ending–Lomba’s imprisonment–appears as the first chapter, the reader experiences a sense of déjà vu throughout the reading of the novel, as the action backtracks, forcing the reader to experience the events which led up to the opening chapter and to wonder if anything could have prevented Lomba’s eventual imprisonment. Habila makes us think, ponder the fragility of democratic institutions which we take for granted, and explore how the slow erosion of rights can lead to the rise of dictators who seize absolute power to continue their rule. Though the drama and violence are presented with almost journalistic clarity, the novel’s emotion is engendered by our identification with the characters and our ability to understand that these are people not much different from ourselves, people who through no fault of their own have become victims of circumstance and the power of a military controlled by one man.

Habila’s novel is a powerful defense of the freedom of the press and a celebration of the lives of those courageous writers who have refused to be silenced, even when faced with death. As he says, “Every oppressor knows that wherever one word is joined to another word to form a sentence, there’ll be revolt. That is our work, the media: to refuse to be silenced, to encourage legitimate criticism wherever we find it.” This moving study of idealistic young people refusing to give up, even when faced with threats to their very lives, is an unforgettable story of the human spirit waiting for an angel–and sometimes meeting the Angel of Death.

Habila’s novel is a powerful defense of the freedom of the press and a celebration of the lives of those courageous writers who have refused to be silenced, even when faced with death. As he says, “Every oppressor knows that wherever one word is joined to another word to form a sentence, there’ll be revolt. That is our work, the media: to refuse to be silenced, to encourage legitimate criticism wherever we find it.” This moving study of idealistic young people refusing to give up, even when faced with threats to their very lives, is an unforgettable story of the human spirit waiting for an angel–and sometimes meeting the Angel of Death.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://thenewsafrica.com

Strongman Sani Abacha inspects his troops: http://www.nigeriamasterweb.com

General Sani Abacha and his hitmen, led by Hamza Al Mustapha, are accused of having chased and murdered Mrs. Kudirat Abiola, in cold blood on the streets of Lagos. Mrs. Abiola was the senior wife of Moshood Abiola, an Abacha opponent, who was the presumed winner of the annulled Nigerian elections of 1993. http://www.celebratekudiratabiola.info

Writer Ken Saro-Wiwa’s last words and photo appear here: http://babajidesalu.wordpress.com