“The crime at the House of Swaps was by no means the only one of its kind. Since this book’s thesis – that the history of a city is the history of its crimes – cannot be proven merely by presenting one case study, I have decided to mix into the larger narrative certain reports of crimes that, in a sense, foreshadow it.”–the Author.

The metafictional author of this statement has been a member of the “Unesco Standing Committee on The Theory and Art of the Police Novel, headquartered in London and financed by Scotland Yard.” As a member of the Fourth Panel, his task has been to study real-life “perfect crimes” from the great world capitals and to compare their true nature to their literary counterparts. While studying the crimes of Rio de Janeiro, he notes that one “perfect crime” stands out from the rest, not because of the difficulty in uncovering evidence but because of the “logical impossibility of accepting the solution.” His work with the Committee runs into difficulties, however. A spontaneously emotional person, he finds that his British counterparts on the Committee are “incapable of grasping notions of chance or disorder; they were ponderous, restrained, punctual.” When he loses his job, he decides to keep his files, which he uses to write this novel. Although his story can be read as a detective novel, “it can also be read as an adventure story, a ‘treasure hunt’ of sorts, filled with duels, ambition, and revenge. It is thus closer to Dumas than to Melville or Conrad.”

The metafictional author of this statement has been a member of the “Unesco Standing Committee on The Theory and Art of the Police Novel, headquartered in London and financed by Scotland Yard.” As a member of the Fourth Panel, his task has been to study real-life “perfect crimes” from the great world capitals and to compare their true nature to their literary counterparts. While studying the crimes of Rio de Janeiro, he notes that one “perfect crime” stands out from the rest, not because of the difficulty in uncovering evidence but because of the “logical impossibility of accepting the solution.” His work with the Committee runs into difficulties, however. A spontaneously emotional person, he finds that his British counterparts on the Committee are “incapable of grasping notions of chance or disorder; they were ponderous, restrained, punctual.” When he loses his job, he decides to keep his files, which he uses to write this novel. Although his story can be read as a detective novel, “it can also be read as an adventure story, a ‘treasure hunt’ of sorts, filled with duels, ambition, and revenge. It is thus closer to Dumas than to Melville or Conrad.”

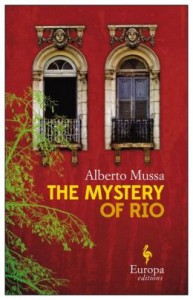

The novel’s “perfect crime” takes place on June 13, 1913, a Friday, at the House of Swaps, once the estate of the Marquise of Santos but currently owned by Polish Doctor Miroslav Zmuda, who uses it as a gynecological medical clinic during the day. At night, however, it becomes the city’s most exceptional brothel, a place where men rent the services of prostitutes dressed as nurses and where women, too, may rent the services of men. In fact, it is also open to couples who can meet there secretly without their spouses knowing about their liaisons, thanks to the back door and a rumored secret tunnel from the premises to the palace which belonged to Emperor Pedro I in the early nineteenth century. On June 13, however, a murder takes place at the brothel. The personal Secretary to the President has been a client of Fortunata, but she leaves shortly afterward, and a couple of hours pass before the House realizes that the Secretary’s nap has lasted longer than normal.

Back entrance to the former home of Marquise of Santos, depicted as a clinic and brothel in this novel, now the Museum of the First Empire. Photo by RNLatvian

When they open the door, they discover the Secretary gagged, with his wrists and ankles tied to the bedposts, whip lashes on his body, and his neck bearing the marks of deep thumb prints. Nothing has been stolen from him. Forensics specialist Sebastiao Baeta is chosen to investigate. Baeta, as a client of the House and as the person in charge of the new Civil Police Museum, already knows all the people he needs to contact and understands the need for discretion in his investigations. He soon discovers Fortunata’s gold earrings in the hands of an old man named Rufino, reputed to be a sorcerer, who claims they were payment to him by Aniceto Conceicao, the twin brother of Fortunata.

Almost immediately after these introductory scenes, the author begins his promised digressions into the city’s past history, which he presents out of chronological order, with stories ranging from the sixteenth century to the present and all eras in between – “the concept of city is independent of the concept of time.” In due course, he discusses the secret tunnels beneath two of the oldest religious orders in Rio, the Benedictines and the Jesuits, who are thought to have used them to transport fabulous treasure to the Calabouco River and then to the Atlantic before these priests were expelled from the city. That then brings up the subject of treasure, which leads to additional stories of pirates, which leads to stories of witches, and then to grave-robbing, as Beata learns that a mass grave in the English Cemetery has been vandalized and bodies dug up.

Author Lima Barreto, an occultist who wrote short stories based on cases he had studied, and a source of information for this novel.

The desecration of the cemetery stimulates a discussion of the Tupi in the sixteenth century and of cannibal spirits. Rio itself, the author tells us, “arose from a desecrated cemetery,” and the trading in corpses for medical research continued for more than a century, during which “casumbis” (zombies) were resurrected to become their creators’ slaves. And that brings up the subject of slavery and the arrival of an Ashanti prince from the Ivory Coast who wanted to expand the slave trade and who brought great treasure with him to ensure this.

Back and forth the narrative rambles, adding small bits to the story of the murder and much more information about the history of the city. Eventually, the author begins tackling sociological issues, discussing adultery as a cultural characteristic, and bringing up the subject of the “capoeiras,” practitioners of martial arts brought to the city by African slaves and Creoles, who believed that no woman could be guilty of adultery, that the fault was all with the men. And this reminds the author of duels between men for the favor of females. Eventually, Aniceto, Fortunata’s brother, brazenly challenges Baeta, the policeman, to vie for the hand of one of the women he “owns,” giving him five years to succeed. And that turns the subject to sexuality and its practices, what works and what does not.

The novel has won several prizes in the author’s native Brazil, and part of the book’s popularity there undoubtedly relates to the fact that natives of Rio would be familiar with many, if not most, of the names, places, and cultural entities being described during all the historical diversions. For those of us who are not, however, the interruptions in the main story become frustrating, especially since the historical information, all new, is given in random chronological order, “independent of the concept of time.” The thin characters show little empathy with each other, showing instead feelings of anger, jealousy, and fear of humiliation, and the book appears to have been written for a super-macho male audience. There are few female characters, and those who do appear are prostitutes and married women looking for pleasure, there being little distinction between them – all are treated as objects. Although the setting is a hundred years ago, when women were much less liberated than they are now, the book is written in the present and presumably hopes to appeal to a female audience, too. That may be a hard sell here.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://wp.clicrbs.com.br

The photo of the back entrance to the former home of the Marquise of Santos, which appears here as Dr. Zmuda’s clinic and brothel, is by RNLatvian on http://www.panoramio.com/ The book contains a floor plan of the building, and the curved, oval room shown here is clearly visible in the floor plan.

The Police Headquarters and Civil Museum, new during the time of this novel, may be found here:

http://www.americapictures.net/

A Nova California by Lima Barreto, a collection of short observations and stories by an occultist from Rio, serves as a resource for this novel and is from http://www.goodreads.com/

The Imperial Palace, now a museum, appears on http://gobrazil.about.com/ Pedro I took his oath of office on the front balcony, a picture that is recorded here: http://en.wikipedia.org/

ARC: Europa