“This night is not an average night….Veronica hasn’t come back from her drawing class. When she returns, the novel will end. But as long as she is not back, the book will continue… until she returns, or until Julian is sure that she won’t return. For now Veronica is missing from the blue room, where Julian lulls the little girl [her daughter] to sleep with a story about the private lives of trees.”

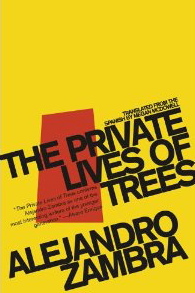

Described a s “the greatest writer of Chile’s younger generation,” Alejandro Zambra has won numerous prizes, including Chile’s National Critics’ Prize for his previous novella, Bonsai. Like that novella, The Private Life of Trees is also a small, carefully constructed work which achieves elegance and significance through its careful pruning of unnecessary detail from the story at its heart. Like Bonsai, too, this novel calls little attention to itself, preferring to let its reflection of universal truths and its grounding in reality speak for themselves.

s “the greatest writer of Chile’s younger generation,” Alejandro Zambra has won numerous prizes, including Chile’s National Critics’ Prize for his previous novella, Bonsai. Like that novella, The Private Life of Trees is also a small, carefully constructed work which achieves elegance and significance through its careful pruning of unnecessary detail from the story at its heart. Like Bonsai, too, this novel calls little attention to itself, preferring to let its reflection of universal truths and its grounding in reality speak for themselves.

Zambra is a unique writer, one who belies the stereotype of a writer as someone who becomes impassioned by an idea, then hies off to his quiet garret to write furiously, developing, refining, and then ultimately promoting it. Zambra, like his alterego Julian, also an author, ties himself to the most mundane aspects of everyday life, which he then describes succinctly and, at times, lovingly. There are no spectacular scenes, no dramatic displays of emotion, and no real plot here, just the story of Julian, a university professor who teaches all week, entertains his stepdaughter with a continuous story of the private lives of trees, and on Sundays works on his novel, a long project which was once three hundred pages but which he, calling himself a “self-policeman,” has whittled down to a mere forty-seven pages. His novel is about a young man tending a bonsai tree, similar to the one given to him by his friends, and which he has neglected to the point that it may die.

Julian has been happily married for three years to Veronica, who brought her five-year-old daughter Daniela into the marriage, and it is for Daniela that he tells his never-ending story of trees, in which a poplar tree and a baobab tree are the protagonists. On most evenings after Julian and Veronica put Daniela to bed, they go into the “green room,” a studio/library of sorts, where Julian reads and writes, and where Veronica does her artwork. On this evening, however, Veronica has gone to her art class and has not come home. Julian is not worried about her at first, but before long, he begins to wonder whether she will, in fact, return to him. He passes the time that night writing about her, their life together, and their past lives, and he says he will stop writing when she returns home, or when he is convinced that she will not return.

As he writes, the reader comes to know something about all the characters and about the writing process. Time passes as in a dream during Julian’s long night of writing, with present and past overlapping, memories surfacing and vanishing, and Julian’s imagination creating new scenarios which get interrupted and then change directions. He envisions Daniela someday reading the thoughts he has recorded about her mother and him and about their marriage—maybe when she is thirty.

When Julian’s writing ends, author Zambra continues. Using the point of view of Daniela, he shows her as an older woman as she considers reading Julian’s novel, which she thinks may be, like all fiction, just “novelists’ absurd farces.” As Zambra touches on the process of writing fiction, what it means, and whether it is important, however, he moves into the future, giving a conclusion to Julian’s thoughts and demonstrating the power of fiction to create whole worlds.

author Zambra continues. Using the point of view of Daniela, he shows her as an older woman as she considers reading Julian’s novel, which she thinks may be, like all fiction, just “novelists’ absurd farces.” As Zambra touches on the process of writing fiction, what it means, and whether it is important, however, he moves into the future, giving a conclusion to Julian’s thoughts and demonstrating the power of fiction to create whole worlds.

Filled with warmth and a sly sense of humor about writing, about life in Chile, and about his main character Julian, who is often ineffective, Zambra creates a wonderful irony—it is almost impossible to remember that the main character is Julian and not Alejandro Zambra, a similarity he cultivates throughout, especially with his references to the art of bonsai (which was the main subject of Zambra’s previous novel) and the act of “self-policing” by an author who reduces big stories to very small novellas. Those who believe that “more is better” may be surprised at how much Zambra can reveal in the belief that “less is more.”

ALSO by Zambra: MY DOCUMENTS

Notes: The author’s photo by Leandro Chavez is from http://www.lanacion.cl

The bonsai depicted here is from: www.bonsai4me.com