“It was a party that had lasted too long; and tired of the voices, a little too animated, and the liquor, a little too available, and thinking it would be nice to be alone, thinking I’d escape, for a brief interval, those smiles which pinned you against the piano or those questions which trapped you wriggling in a chair, I went out to look at the ocean.”

This opening sentence alone would be enough to send many readers into shivers of delight, as it reveals in relatively few words so much more information than one has learned to expect from a single sentence, even from major authors, in this era of quick tweets and sound bites. While the speaker of this novel is enjoying his view of the ocean, he sees a young woman on the beach below, drinking from a glass and “experiencing… some divine rapport with the sea.” The undertow suddenly draws her down, but she rises again, then begins to walk deeper, and the speaker realizes that “she wasn’t, as I had thought, wading.” Leaping off the porch, he pulls her ashore, and tries to pump out the water that has almost drowned her. Revealing more about himself than he probably intends, however, he admits, “I felt rather silly, and the position was obscene, and the damn sand was all over my slacks.” The rest of the party, all Hollywood people and hangers-on, are not especially upset by the near-drowning, one of them even remarking, when she revives, that “She’s going to taste salty for a week.” The speaker himself callously tells his host, “Next party you invite me to, I’ll carry a respirator.”

This opening sentence alone would be enough to send many readers into shivers of delight, as it reveals in relatively few words so much more information than one has learned to expect from a single sentence, even from major authors, in this era of quick tweets and sound bites. While the speaker of this novel is enjoying his view of the ocean, he sees a young woman on the beach below, drinking from a glass and “experiencing… some divine rapport with the sea.” The undertow suddenly draws her down, but she rises again, then begins to walk deeper, and the speaker realizes that “she wasn’t, as I had thought, wading.” Leaping off the porch, he pulls her ashore, and tries to pump out the water that has almost drowned her. Revealing more about himself than he probably intends, however, he admits, “I felt rather silly, and the position was obscene, and the damn sand was all over my slacks.” The rest of the party, all Hollywood people and hangers-on, are not especially upset by the near-drowning, one of them even remarking, when she revives, that “She’s going to taste salty for a week.” The speaker himself callously tells his host, “Next party you invite me to, I’ll carry a respirator.”

In clear, precise, and evocative language, author Alfred Hayes explores the intense and potentially dangerous relationship which eventually develops between the self-absorbed speaker and the woman he rescues, two flawed people whose accidental meeting leads to an affair. Their relationship is complex and fraught with emotional pitfalls, but Hayes, who wrote this classic novel in 1958, credits the reader with the intelligence to read between the lines and to recognize the differences between what the characters say and do and what they really mean and think. The author spent much of his career writing screenplays, both in Hollywood and in Europe, and he uses the skills he developed in writing for films to great advantage here. His economy of language, a necessity for great film scenes, allows him to develop a novel in which the reader becomes a participant, imagining the dramatic pauses in dialogue, the tones of conversations, and the words a character does not say at times in which s/he might be expected to reveal something crucial. As a result, this brief novel, close to a novella in length, is so finely tuned that upon reading it for the second time, the reader gains even more appreciation of the author’s technique – and his brilliance.

Significantly, the author never names the main characters. To do so would imply that each is unique, and that would not be true. The male speaker, in his late thirties, has been moving back and forth between New York and Hollywood for writing jobs for five years, but he is not a star, having “earned a salary somewhat in excess of what they paid an aged vice-president of a respectable bank” but with no recognition and little self-respect. He has been married for fifteen years, though the marriage has deteriorated, and on this trip to Hollywood, he plans to stay for four months, leaving his wife and eight-year-old daughter in New York. When the woman he has rescued asks if he is writing for a studio now, he says, no, that “[he] was writhing…a member of the Screen Writhers Guild.”

Significantly, the author never names the main characters. To do so would imply that each is unique, and that would not be true. The male speaker, in his late thirties, has been moving back and forth between New York and Hollywood for writing jobs for five years, but he is not a star, having “earned a salary somewhat in excess of what they paid an aged vice-president of a respectable bank” but with no recognition and little self-respect. He has been married for fifteen years, though the marriage has deteriorated, and on this trip to Hollywood, he plans to stay for four months, leaving his wife and eight-year-old daughter in New York. When the woman he has rescued asks if he is writing for a studio now, he says, no, that “[he] was writhing…a member of the Screen Writhers Guild.”

Though she is not gorgeous and is not especially talented, she thinks of herself as an actress, and though she rarely gets call-backs, she stays because of the “usual compulsions: my face for the world to see.” The speaker responds to her neediness because he, too, is lonely in Hollywood. Gradually, their individual problems become clearer. She imagines a grand life in which she will be a success, when “inevitably, someday, the limousine drove up, the emissary knocked, and it would be over, at last, the great trial by loneliness and hunger.” He expects nothing more than his next paycheck.

A trip to the bullfights in Tijuana becomes the turning point for these two (and anyone who has ever seen a bullfight knows how little the reality resembles the supposed grandeur of the spectacle), and the author’s description of the several aspects of this scene will break the heart of even a stoic reader.

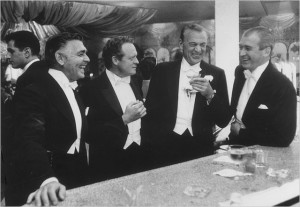

Romanoff’s Restaurant, which features in the novel, is where the elite of Hollywood gathered – stars like Clark Gable, Van Heflin, Gary Cooper, and Jimmy Stewart

Alfred Hayes keeps the reader totally engaged, even with characters who are often less than engaging. His control of both his material and his literary objectives is absolute, his writing style is flawless, and he never has to resort to literary trickery to keep the reader focused on two characters who, despite their lack of uniqueness are, nevertheless, emotionally exposed to the reader and for all the world to see. One of my new favorite authors, Alfred Hayes deserves to emerge from his literary obscurity and, if New York Review Books, with their current reprints, have anything to do with it, he will.

ALSO by Alfred Hayes: THE GIRL ON THE VIA FLAMINIA , IN LOVE, and. THE END OF ME

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.losinrocks.com

“Night-time at the Beach” is from http://www.wallpaperid.com

The matador painting may be found on http://www.canvaz.com

The photo from Romanoff’s appears on http://forum.skyscraperpage.com

ARC: New York Review Books