“There were no words at all for the enormous charity that having a woman, in a room with a closed door, in a bed that was one’s own, meant. He touched her with a quality of wonder and thankfulness. She said nothing. She did not move. But it was not necessary for her to say anything or even to give him anything. It was just the tremendousness of her being there. And he could not tell her that.”

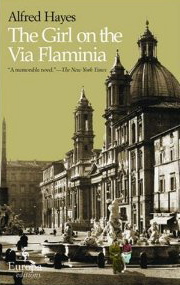

The liberation of Ro me during World War II was not a “liberation” to many of its inhabitants after the occupying American and British armies took up residence. The initial joy at the Germans’ departure had faded, six months later, as many Italians began to resent what they regarded as the occupiers’ sense of entitlement and superiority. Perfectly capturing the atmosphere and changing moods of the times, author Alfred Hayes creates a microcosm of Roman life in the home of the Pulcini family on the Via Flaminia. Adele, the mother, needing funds and food, uses her dining room as a small café for a handful of American and British soldiers in the evening, and, if they need “company,” she arranges for them to meet Italian women.

me during World War II was not a “liberation” to many of its inhabitants after the occupying American and British armies took up residence. The initial joy at the Germans’ departure had faded, six months later, as many Italians began to resent what they regarded as the occupiers’ sense of entitlement and superiority. Perfectly capturing the atmosphere and changing moods of the times, author Alfred Hayes creates a microcosm of Roman life in the home of the Pulcini family on the Via Flaminia. Adele, the mother, needing funds and food, uses her dining room as a small café for a handful of American and British soldiers in the evening, and, if they need “company,” she arranges for them to meet Italian women.

When one of the residents of the Pulcinis’ house departs, the Pulcinis’ maid arranges for her friend Lisa Costa, from Genoa, to move into the room. Lisa, a “nice girl” is desperate. Out of food, out of money, and with no job prospects in Genoa, she has agreed to pose as the wife of an American soldier at the Pulcinis’ house in exchange for food and shelter. Robert Guard, her “husband,” is a lonely, young American who wants company, someone to talk to, and even, perhaps, to take to bed, but he especially wants a sense of “home,” and he hopes Lisa will provide these.

The pas de deux between Robert and Lisa is beautifully rendered, as author Alfred Hayes shows their awkward relationship and Robert’s clumsy attempts to establish some sort of communication with Lisa. Lisa resents having to live with Robert, whom she regards as a “barbarian conqueror,” while he fails to understand that she has her own needs which go beyond food and shelter. He is not self-aware enough to know what he is doing wrong, though he never forces her to act as a prostitute. The first sign that he may connect with her occurs in one beautifully sensitive and subtle scene, in which he woos her with a package of instant soup and some of his mother’s Christmas cake.

Against this backdrop of failed connections looms Antonio, the Pulcinis’ son. Once a soldier in the Italian army, he has deserted after watching the death of his best friend and after suffering his own terrible wound during their retreat from southern Italy. For two months, until the “liberation,” his parents hid him in their dark cellar, and his isolation, his guilt at having deserted, his pain from his wounds, and his frustrated patriotism and resentment against the “liberating” armies from the west have left him unstable. Proud and unwilling to accept defeat, he sees himself as a man who must constantly embody the glories of Italy and its culture, and he regards it as his mission to reprimand and punish his fellow Italians who may have “forgotten” their heritage in the traumatic aftermath of the war.

Written in 1949 by Alfred Hayes, one of the premier writers of the period, The Girl on the Via Flaminia (recently reprinted by Europa Editions) shows Hayes’s experience as an honored and respected screenwriter. This sensitive and gorgeously wrought study of connections and misconnections contains dialogue that one can only hope will one day be transformed for the stage or screen. As much a drama as it is a novel with intense scenes, this masterpiece of the period perfectly captures a short, but unique, period in history—the months in which Rome was “liberated” and then occupied by western armies—a period which deserves revisiting, either in the form of this novel or as a play or film.

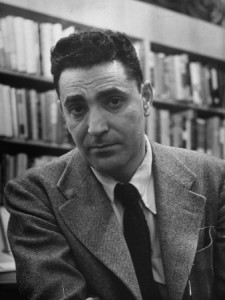

The themes of occupier vs. occupied, military “conquerors” vs. prideful populations who do not regard themselves as “conquered,” and individuals caught up in personal crises within a governing structure over which they have no control are as universal and a propos today as they were almost sixty years ago. Hayes, a brilliant creator of scenes who deserves a much wider appreciation than he currently enjoys, gives each of the main characters his/her own point of view in various sections of the novel, enhancing the reader’s understanding of the conflicts which brew beneath the surface of this character-driven novel. And when the climax occurs at the end, the characters have been so carefully drawn and the symbolism has been presented so clearly that no careful reader will be surprised by the outcome. The novel is short, but it radiates with life.

ALSO by Alfred Hayes: MY FACE FOR THE WORLD TO SEE, IN LOVE, THE END OF ME

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.art.com/

The photo of the liberation of Rome in June, 1944, appears on http://www.wwiiarchives.net