Note: Jamaican author Andrea Levy is the first person in history to be WINNER of both the Orange Prize and the Whitbread Award in the same year (for SMALL ISLAND in 2004)

“Please pardon me, but your storyteller is a woman possessed of a forthright tongue and little ink. Waxing upon the nature of trees when all know they are green and lush upon this island or birds which are plainly plentiful and raucous, or taking good words to whine upon the curly hot sun, is neither prudent nor my fancy.”

The feisty J amaican narrator of this novel goes on to declare that if the reader does not like her style, “then be on your way, for there are plenty books to satisfy if words flowing free as the droppings that fall from the backside of a mule is your desire.” July, an elderly former slave, is writing her story for her son Thomas, who grew up away from “home” and became educated and trained as a printer in England. July wants him to understand the story of her life – her slavery in Jamaica – and in this way come to know her and their heritage better.

amaican narrator of this novel goes on to declare that if the reader does not like her style, “then be on your way, for there are plenty books to satisfy if words flowing free as the droppings that fall from the backside of a mule is your desire.” July, an elderly former slave, is writing her story for her son Thomas, who grew up away from “home” and became educated and trained as a printer in England. July wants him to understand the story of her life – her slavery in Jamaica – and in this way come to know her and their heritage better.

What follows is a family history, one irrevocably tied to Amity Plantation, where July, the mulatto daughter of Kitty, a slave, and a Scottish overseer, has lived with her mother, accompanying her as she works the plantation in the 1820s. July, while still a child, eventually catches the eye of Caroline Mortimer, the widowed sister of John Howarth, owner of Amity, and she decides to train July as her maid. Wresting her without warning from Kitty, who has no legal rights to her own child, Caroline renames the child “Marguerite” and sets about training her. As July grows and learns to manipulate the self-centered Caroline, Caroline herself becomes less “English,” less “civilized,” and even more autocratic, until she resembles the plantation owners themselves, regarding their workers as property, not as humans.

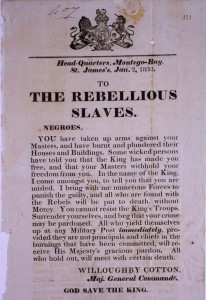

When a preacher arrives on the island and advocates emancipation, he stimulates rebellion on distant plantations, but it is not until Christmas, 1831, that Jamaica’s Great Slave Rebellion takes place, affecting even Amity and changing the face of the entire country. Some fields and plantations are burned. Whites, especially preachers who have opposed slavery, are tarred and feathered by other whites. Even a white child suffers the wrath of slave-holders when he is sealed in a barrel into which long nails are hammered and then rolled down a hill, an act which John Howarth finds “a little wanton” and “not the act of gentlemen.” With his own loyalties in question, however, Howarth unexpectedly leaves the plantation to the control of the tempestuous Caroline.

On July 31, 1838, slavery is officially ended, by order of the Queen of England, and in the second half of the novel, July’s narrative becomes less the story of slavery and its effects in general and becomes more personal – the story of July as an adult – free, but dependent – as she uses her beauty and talents for her own ends. Ironically, Caroline, too, is also dependent – on July, on her husband, and on the workers who will no longer accept the plantation’s demands regarding their hours, the number of days a week they must work, and, eventually, the rents they are charged for their houses and provision grounds. Full-scale rebellion by the freemen is inevitable. Though the plantation owners are desperate to harvest their crops, the workers do not understand the economy in which they suddenly find themselves. For both groups, the issue is power, and no one can win.

On July 31, 1838, slavery is officially ended, by order of the Queen of England, and in the second half of the novel, July’s narrative becomes less the story of slavery and its effects in general and becomes more personal – the story of July as an adult – free, but dependent – as she uses her beauty and talents for her own ends. Ironically, Caroline, too, is also dependent – on July, on her husband, and on the workers who will no longer accept the plantation’s demands regarding their hours, the number of days a week they must work, and, eventually, the rents they are charged for their houses and provision grounds. Full-scale rebellion by the freemen is inevitable. Though the plantation owners are desperate to harvest their crops, the workers do not understand the economy in which they suddenly find themselves. For both groups, the issue is power, and no one can win.

Andrea Levy is a masterful writer, with a sense of drama, the ability to use it to create a lively narrative, and a fine eye for detail (Caroline’s curls on the sides of her head bounce “like small birds pecking at her shoulder”). Her subject of slavery, by its very nature, achieves power with very little embellishment (as July points out in the introduction), her characters elicit both sympathy and fury, and the novel moves quickly, with no lagging. Many readers will find it a non-stop read. Others, however, may become impatient with the fact that, despite its unusual setting, it highlights injustices and atrocities similar to those in many other historical novels about slavery and plantation life. July, as the main character, is lively and intriguing, but she is not always able to keep the narrative fresh and “new.”

Though July’s point of view is colorful and engaging, the author sometimes needs to convey information which July has no way of knowing, and this creates some problems regarding the consistency of voice. In addition, when July’s son Thomas makes suggestions regarding her finished narrative and suggests that July fill in missing information, she is sometimes frivolous and invents “facts.” Sometimes, Levy herself fills in the blanks, in one case including Thomas’s own (necessary) history as an “excerpt” from a story written by his adoptive mother and published in a Baptist pamphlet in England, a device that, unfortunately, feels like a device. The novel is well-researched, however, with dialogue which conveys all the emotions one would expect of conflicted characters. Ultimately, The Long Song offers a view of Jamaican history which Levy’s fans will celebrate.

Though July’s point of view is colorful and engaging, the author sometimes needs to convey information which July has no way of knowing, and this creates some problems regarding the consistency of voice. In addition, when July’s son Thomas makes suggestions regarding her finished narrative and suggests that July fill in missing information, she is sometimes frivolous and invents “facts.” Sometimes, Levy herself fills in the blanks, in one case including Thomas’s own (necessary) history as an “excerpt” from a story written by his adoptive mother and published in a Baptist pamphlet in England, a device that, unfortunately, feels like a device. The novel is well-researched, however, with dialogue which conveys all the emotions one would expect of conflicted characters. Ultimately, The Long Song offers a view of Jamaican history which Levy’s fans will celebrate.

Note: Also reviewed here: Levy’s SMALL ISLAND

The author’s photo and an interview appear here: www.thecommonwealth.org.

The Letter to Rebellious Slaves, written by Major General Willoughby Cotton, may be read in its entirety here: http://abolitionwya.org.uk

The cane fire photo appears on www.deltabackpackers.com. Those interested in learning how and why cane fields are routinely burned before harvest will find answers on this site: www.sucrose.com