Note: The Old Gringo (1985) was the first American bestseller written by a Mexican author.

“[The Old Gringo said] that to be stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags was a pretty good way to depart this life. He used to smile and say: ‘It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stairs.’ ”

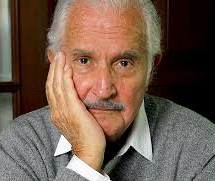

Though this novel has all the hallmarks of a recognized classic, it is, surprisingly, only twenty-five years old, a book first translated into English in 1985. Carlos Fuentes, the author, brought up by his diplomat parents in the US and throughout Latin America, has always been particularly aware of differences in cultures, and in this novel he elaborates on the differences between the US and Mexico, sensing more than most other writers the inherent, conflicting goals of the two countries. Through the action, set during Mexico’s civil war in 1914, the author shows Mexico determined to be independent in its own right and true to its own history, while the US wants to create outcomes there which coincide with US goals and political agendas here. For more than forty years, Fuentes has also been fascinated with the story of American author/journalist Ambrose Bierce, who is believed to have vanished in Mexico during that war, and he exploits this long interest by making Bierce the “Old Gringo” of the title.

Though this novel has all the hallmarks of a recognized classic, it is, surprisingly, only twenty-five years old, a book first translated into English in 1985. Carlos Fuentes, the author, brought up by his diplomat parents in the US and throughout Latin America, has always been particularly aware of differences in cultures, and in this novel he elaborates on the differences between the US and Mexico, sensing more than most other writers the inherent, conflicting goals of the two countries. Through the action, set during Mexico’s civil war in 1914, the author shows Mexico determined to be independent in its own right and true to its own history, while the US wants to create outcomes there which coincide with US goals and political agendas here. For more than forty years, Fuentes has also been fascinated with the story of American author/journalist Ambrose Bierce, who is believed to have vanished in Mexico during that war, and he exploits this long interest by making Bierce the “Old Gringo” of the title.

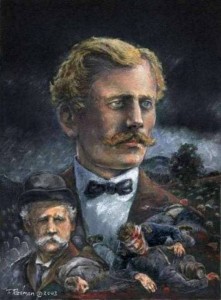

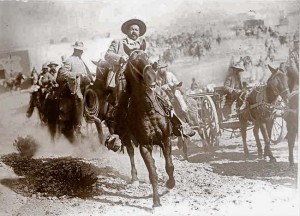

Bierce, age seventy-one at the time of his disappearance (sometime in 1914), had traveled the world and had already written most of what he felt he had to say. He had no existing relationship with anyone in his family, and the one place which drew him at the end of his life was Mexico, where the popular revolution was threatening to change the history of Mexico. Not incidentally, it was also endangering the large tract of land “owned” by William Randolph Hearst, for whom Bierce had worked as a journalist. Hearst and the owners of other large haciendas had obtained thousands of acres of land through their connections with the Mexican government, at the expense of the campesinos who had been working the same land for generations. Committed to the rights of the underdog, Bierce, it is believed, went to Mexico to join up with Pancho Villa and his men, who were fighting the federales and the government of President Victoriano Huerta, known as “the Jackal.” Bierce never returned, his fate unknown.

Using this broad outline of what is known about Bierce, Fuentes writes a fascinating novel on many different levels. On the level of plot, it is a story set in 1914 and told by Harriet Winslow, a thirty-one-year-old American from Washington, D.C., who has accepted the job of teacher to the children of the wealthy Miranda family. When the Miranda hacienda is overrun by rebels, and her employers leave hastily, Harriet is left without a job and without any prospects. Conveying an almost mystical sense of destiny, Fuentes uses flashbacks to reveal Harriet’s background and that of the Old Gringo, who has just arrived in the lands around Camargo, Chihuahua. Harriet regards the seventy-one-year-old Gringo as a father figure, understanding that he has come to Mexico to die, while he in turn, “too brave for his own good,” sees her as the final temptation before his death. Harriet has had a brief but passionate relationship with Tomas Arroyo, the general who has driven out the Miranda family and hanged many of the federales protecting the property. She is tormented by that relationship—glad to have had the experience of uninhibited sexual passion but furious with Arroyo “for showing her what she could be and then forbidding her to ever be what she might be.

Ambrose Bierce, by Tom Redman

Fuentes clearly admires the Old Gringo for his sense of honor and moral rectitude, but he also shows him to be human, a man grappling with his future, even as he believes that he has no future. Like many other characters in the novel, including Harriet Winslow and Tomas Arroyo, who have lost their fathers, the Old Gringo has also lost his family. The sense of each person’s connection to the past through family permeates the novel, just as people and families are connected to their country through the land. As the characters separately try to make their own lives worth living, they parallel the goals of the rebels who, as hard-working poor, are determined to remember and protect their own past and their relationship to their country’s history.

The novel’s outcome—the Old Gringo’s death—looms over all the action from the outset, which begins with a grim scene in which his body is being exhumed for shipment back to the US, but the novel is not just a story on one level. It is also a story illustrating the political differences between Mexico and the US, between a country with a long and complex cultural history and one that is not even two hundred years old, and between the poor and helpless victims of economic and political aggression and their exploitation by wealthy autocrats, some of them American, who benefit from their connections to a corrupt Mexican government. Tomas Arroyo, the illiterate general, has considered himself honor-bound to protect the legal papers proving the ownership of vast land areas by the poor farmers who have worked it for generations, and he and the other rebels are determined to expel and/or kill those who deny these rights, hoping to topple the government in the process.

Pancho Villa

Fuentes spends much time describing the characters’ philosophical quandaries (some of them repetitious), but he also includes suggestions of Mexican myths, especially myths related to the sun, moon, and stars. Nature comes to life here, and symbols abound—the desert being the ultimate image of war, with its tough plants protected by thorns, and its animals, such as scorpions and poisonous snakes possessed of natural weapons. These images contrast with artificial excesses of church décor and, on a smaller scale, with the Miranda hacienda and its elaborate mirrored ballroom, in which many soldiers see their full images for the first time. The contrasts between real life and its artificial reflections, between the realities of war and the perhaps unrealistic dreams of its participants, and between remembered history and its loss, add significance and thematic richness to the author’s seemingly simple story. Ultimately, the differences between the two gringos–Bierce and Harriet Winslow–and the Mexicans they meet at this critical time in history provide the fulcrum upon which Fuentes explores the disconnections between the United States and Mexico. As Bierce himself says, “To be a gringo in Mexico, that is euthanasia.”

Notes: Fuentes’ photo from www.joschwartz.com.

Photo of Bierce is a painting by Tom Redman on the Ambrose Bierce website, showing Bierce in several phases of his life: http://donswaim.com

Photo of Villa from www.old-picture.com