Note: This novel was WINNER of three major French Prizes: the Sang d’Encre, the Michael Lebrun Prize, and the SNCF Crime Fiction Prize.

“Civilization…You conquered native peoples in the same spirit as a trainer taming a wild animal. Your explorers, your great discoverers, your co-called heroes not only plundered our economic resources but also our art, our very culture!…You stole our history, our languages, [and] our customs, and imposed…what you call your values.”–Hana

French author Caryl Ferey’s previous novel Zulu, winner of multiple prizes, was set in South Africa; Utu, also winner of multiple prizes, is set in New Zealand. Both novels, dark and full of violence, depend on the internal conflicts within a country for their dramatic impact and plot, and both feature longstanding resentments between an upper ruling class, and the dispossessed original residents of the country who were conquered during the colonial period. Here, the New Zealand government based in Auckland is struggling to deal with the numerous social problems involving the Maoris, whose culture and way of life have become almost extinct. “Underqualified” for jobs, twenty percent are unemployed, the author points out. Large numbers of families are on welfare, and they have lost their lands. Most no longer speak their own language, and they are “overrepresented” among the prison population. “Marginalized and impoverished, many Maoris [are] now forced to seek refuge in the cities,” making do as well as they can.

French author Caryl Ferey’s previous novel Zulu, winner of multiple prizes, was set in South Africa; Utu, also winner of multiple prizes, is set in New Zealand. Both novels, dark and full of violence, depend on the internal conflicts within a country for their dramatic impact and plot, and both feature longstanding resentments between an upper ruling class, and the dispossessed original residents of the country who were conquered during the colonial period. Here, the New Zealand government based in Auckland is struggling to deal with the numerous social problems involving the Maoris, whose culture and way of life have become almost extinct. “Underqualified” for jobs, twenty percent are unemployed, the author points out. Large numbers of families are on welfare, and they have lost their lands. Most no longer speak their own language, and they are “overrepresented” among the prison population. “Marginalized and impoverished, many Maoris [are] now forced to seek refuge in the cities,” making do as well as they can.

This complexly plotted novel begins with a vivid picture of Paul Osborne, a former Auckland police lieutenant collapsing drunk and under the influence of drugs on a beach in Australia, near Sydney. Suffering from a blackout, he does not even remember how he got where he is, and when he returns to his Sydney apartment, he finds Auckland Lt. Gallagher, never a favorite, waiting for him, wanting his help in finding the killers of six white policemen (pakehas) back home in Auckland. Osborne’s only friend on the force, Jack Fitzgerald, has reportedly committed suicide while working on this case, and though Malcolm Kirk, the Maori prime suspect in several deaths is now dead, a new mass grave has been found in a forest near Auckland. No body has been found for Kirk’s second in command, Zinzan Bee, an activist and symbolic figure in Maori society, though Fitzgerald said on the radio before his own death that he had killed Bee. Questions have arisen as to who is responsible for the most recent deaths of the six police, including Osborne’s half-brother.

A specialist in Maori affairs, Osborne returns home from Sydney and finds that many of the people he has known in the department are among the dead, their positions now filled by insiders. He does not believe that Fitzgerald killed himself. As he continues his (vividly depicted) overindulgence in drink and drugs in Auckland, he is assaulted by memories of the past, including the memory of Hana, a girl of mixed race with whom he fell in love as a teenager and about whom has dreamt for much of his life. When he starts to investigate the latest killings, he questions the possible connections of the Mayor of Auckland, his communications advisor, their families, and several other administrators, and as new killings of women begin to turn up, Osborne suspects that he is being set up for a fall. Eventually, it becomes clear that a real estate deal involving well-connected pakehas in Auckland are connected to the killings. Prime Maori lands are being used for a huge development by non-Maori companies, though how the development came about remains a question.

The plot involving many characters, both white and Maori, becomes so complex that at four or five points in the novel, the author actually backs up and has a character go over the details so far, supposedly reminding himself/herself about what is happening, but in actuality reminding the reader of the various ins and outs of the complicated plot to keep from becoming lost in the maze of detail. Flashbacks to Osborne’s previous life on the force combine with long passages which detail his memories of Fitzgerald and of Hana, years ago, to provide some understanding of Paul Osborne’s life in Auckland, but any understanding gained is superficial, limited by the fact that Osborne is so out of control that he appears to be as much of a psychopath as the men he is chasing.

Part of Europa Editions’s World Noir series, this novel is even more violent than Zulu, Ferey’s previous novel, which I described in my 2010 review as “so upsetting in its depiction of sadistic cruelty against human beings that many readers will be sickened by the level of violence,” and I questioned “how [the novel’s characters] could inure themselves, participate in, or tolerate such horrendous cruelty.” In this novel, even more upsetting, much of the violence originates with the main character, Paul Osborne, a man so savage (whether drunk or sober) that he is impossible to identify  with, much less like. In the course of the novel, he physically attacks and extorts money from six people who once attacked a friend, attacks an elderly woman and throws her on the floor, breaks the nose of a yet another woman who will not tell him what he wants to know (and then threatens to start in on her teeth), throws a man down the stairs, twists the arm and breaks the incisor of a man with whom he is angry, shoots another man in the liver, and kills two policemen and buries their bodies. He is so violent that by the time he mentions that he has just killed his first man, I thought he had killed at least half a dozen. And all this is while acting as an investigator in the police department.

with, much less like. In the course of the novel, he physically attacks and extorts money from six people who once attacked a friend, attacks an elderly woman and throws her on the floor, breaks the nose of a yet another woman who will not tell him what he wants to know (and then threatens to start in on her teeth), throws a man down the stairs, twists the arm and breaks the incisor of a man with whom he is angry, shoots another man in the liver, and kills two policemen and buries their bodies. He is so violent that by the time he mentions that he has just killed his first man, I thought he had killed at least half a dozen. And all this is while acting as an investigator in the police department.

Though the novel may be considered by some to be powerful and dramatic, it gains its power largely through its shock value, through the over-the-top reactions of presumably civilized people, well connected to the Auckland mainstream, who are intent on gaining what they want when they want it, and Paul Osborne is the prime example. The Maoris, however violent they may in this novel, as they seek utu” (vengeance), seem to have ample reason to act as they do, and while some may consider Paul Osborne to be an “anti-hero” (and his actions to represent mainstream “noir”), my own feeling is that there is a difference between the “unsentimental depiction of violence,” one of the main characteristics of noir, and violence for its own sake, which is what I saw here. Osborne is much more than the “alienated, doomed hero” or the “cynical private detective” that usually characterizes noir. He is a dangerous psychopath whose actions are deliberate (or as deliberate as one can expect an alcoholic drug addict’s actions to be). He is in no way a hero.

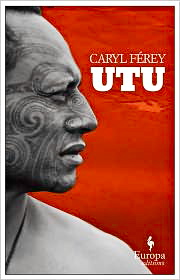

Photos, in order: The author’s photo may be found on http://www.que-leer.com

A traditional marae, the meeting house of a Maori tribe, where some of the action here takes place, is from http://bossclark.com

Three Maori in a dance are wielding patus, small clubs which Osborne uses on one occasion. The women have black tattoos on their lips and decoration on their chins, in traditional fashion, while the man shows a full-face traditional tattoo.

Pink krill appear on the water’s surface on Great Barrier Island, where Osborne has built a cottage, sixty miles from New Zealand’s North Island. http://www.aetoma.com

Using a traditional uhi, a chisel made of bone, which is then hammered into the skin, a man gets a traditional Maori tattoo. The chisel, too, plays a role in this novel. http://www.themaori.com

ALSO by Ferey: ZULU