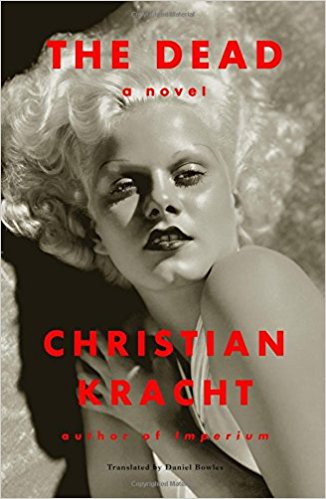

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Hermann Hesse Literature Prize and the Swiss Book Prize in 2016.

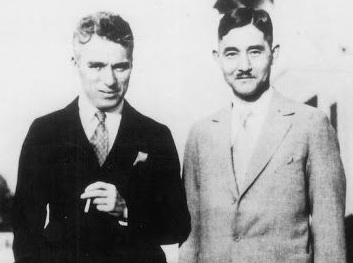

“Droll films in which [Charlie] Chaplin played a down-and-out fellow plagued by bouts of bad luck who still managed to prevail against all odds were enjoying fantastic success in Japan. Something about the inner, utterly anarchic expression of that short, shabbily dressed, always melancholically amused, mustachioed hero, stirred the Japanese soul deeply; they applauded his cinematographic escapades, and his revolt against authority, usually embodied by cretinous policemen, was felt by the audience to be extremely liberating.”

Set in Berlin and Tokyo in the 1930s, Swiss author Christian Kracht’s latest novel offers an unusual fictional vision of the prewar years in Germany and Japan – one in which the primary focus of the author – and ultimately of his two main characters – is not that of reality as much as it is of cinema: Life and the future can be controlled in a film, even if they can not be controlled in real life. At this time, Hollywood is recognized as the center of the film industry, and its stars are recognized throughout the world. With Germany becoming more militaristic and more devoted to expansionist goals, and Japan wanting to counteract the national influence of the Chinese and the seeming omnipotence of American culture, however, it is only a small step before both Germany and Japan decide that the most effective way to accomplish their own specific goals may be to affect national opinion through the production of their own films.

Set in Berlin and Tokyo in the 1930s, Swiss author Christian Kracht’s latest novel offers an unusual fictional vision of the prewar years in Germany and Japan – one in which the primary focus of the author – and ultimately of his two main characters – is not that of reality as much as it is of cinema: Life and the future can be controlled in a film, even if they can not be controlled in real life. At this time, Hollywood is recognized as the center of the film industry, and its stars are recognized throughout the world. With Germany becoming more militaristic and more devoted to expansionist goals, and Japan wanting to counteract the national influence of the Chinese and the seeming omnipotence of American culture, however, it is only a small step before both Germany and Japan decide that the most effective way to accomplish their own specific goals may be to affect national opinion through the production of their own films.

Emil Nageli, a young Swiss film director nearing his thirtieth birthday, has been in Berlin talking with Reich Minister Hugenberg, who believes that a well-made horror film – “an allegory, if you like, of the coming dread” – would attract much attention, even in America. He also wants to involve the Japanese, however, since he believes that they “will sooner or later subdue the Asian continent” and when that happens, he hopes the globe will be “overrun with German films, colonized with celluloid.” Masahiko Amakasu, a Japanese film maker and admirer of Nageli, hopes to establish a relationship with the Germans and arranges for a meeting with Nageli in Japan. Amakasu, too, envisions film changing the world, hoping a Japanese film will “counteract the seeming omnipotence of American cultural imperialism in the realm of film.” As the novel works its way back and forth in time, back and forth between the Germans and the Japanese, back and forth between the two main characters, and back and forth between reality and the imagination, represented here primarily through cinema, the reader is introduced to the characters, in detail, along with their family histories, their personal goals, and just how far they are willing to go to protect themselves and those they love.

A meeting takes place between Nageli and Amakasu at the Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

In the epigraph which introduces the novel, Virginia Woolf is quoted as saying, “What is life? That’s the question. Something not necessarily leading to a plot,” and the author takes this to heart here in The Dead. In a spectacularly dramatic scene, Kracht’s novel begins with a Japanese officer who “had committed some transgression or other [and who] now intended to punish himself in the living room of an altogether nondescript house.” The reader then discovers that a hidden, live camera is recording the young officer’s every movement, every breath, every thought as he disembowels himself, committing seppuku. In the next chapter, young Swiss director Emil Nageli is flying from Zurich to Berlin in an old, shuddering aircraft, and he is “at the end of his tether” – terrified – an ironic juxtaposition of the moods and cultural contrasts between East and West which will also be obvious in later scenes between Nageli and Amakasu. Here both main characters are so obsessed with their own visions of their futures – and their contrasting attitudes toward death and responsibility – that that they fail to distinguish between what is real and what is imagined, and that, according to the epigraph, is what life is all about. It also explains why the novel moves around so much, focusing on a variety of different times, places, and people without connecting all the details into a neat package.

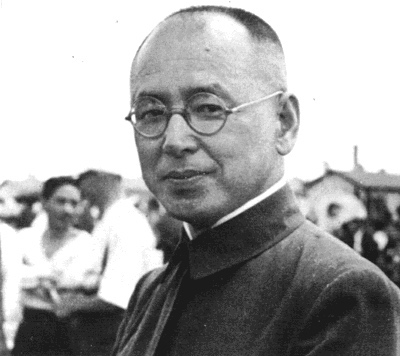

Despite the thin plot which connects all the events described here, author Kracht does develop his characters. Nageli is, except for his career, an ordinary person, described as likable, civilized, sensitive, alert, and sometimes grouchy from low blood sugar, a man becoming more myopic, losing his hair, and having a moon-shaped belly. When he was a child, his father sometimes hit him in the face if he refused to eat his porridge, and he often called him “Philip,” as if he did not remember Emil’s name. On his deathbed, however, Nageli’s father tries to sit up to tell him something important, and then falls back, dead, leaving Nageli desperate to know what his father intended to say, hoping for “absolution, if not pardon.” Masahiko Amakasu’s childhood was a bit different. Able to read by the time he was three and fluent in five languages by age seven, he was already having suicidal fantasies by the age of five, and he often read (and hid in his parents’ garden) a collection of violent picture books. On vacation in Hokkaido, he would hide behind trees and envision his own funeral. Sent to boarding school (which he describes as a “flogging parlor,”), where he was bullied, he eventually acted out his violence against the school.

As these characters develop further, connect, and begin to discuss film in Tokyo, Charlie Chaplin also enters the mix of backgrounds, ideas, emotions, and experiences, and the whole purpose of the film discussions begins to wane. Meeting at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, for whom the hotel has been an enduring monument to the power of imagination and its execution in reality, Nageli, Amakasu, Charlie Chaplin, and Kono, Chaplin’s valet of seventeen years, barely escape the assassination of the Japanese Prime Minister by military cadets. By the conclusion, reality is clearly combining with fiction, further enhancing the themes. Nageli, who is a fictional character, and Amakasu, who was a real officer of the Japanese Imperial Army and the real head of the Manchukuo Film Association, end up on a ship with Charlie Chaplin, eventually arriving in Los Angeles, minus Amakasu. The fates of the other characters seem not to conclude so much as fade, as life ends and imagination continues. As Virginia Woolf would reconfirm from her epigraph, life is not necessarily something leading to a plot, and author Christian Kracht obviously agrees, wholeheartedly.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://norazukker.ch/

Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, is the site of a meeting that includes Nageli, Amakasu, and Charlie Chaplin. http://japantravelcafe.com/

Masahiko Amakasu, head of the Manchukuo Film Association and member of the Imperial Army. https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Charlie Chaplin and his valet of seventeen years, Kono, are also in Tokyo to discuss the role of films. https://www.pinterest.com/