“Don’t be coy, Fergus – I mean Justice O’Reilly. You’ve known me since I was yay high. My name is Tristram St. Lawrence. Tristram Amory St. Lawrence, the thirteenth Earl of Howth….I was – I am – the only son your old pal, the twelfth Earl of Howth, managed to sire, and not for lack of trying. People have been saying a lot of bad things about me in the press. I am here to say a few more.”

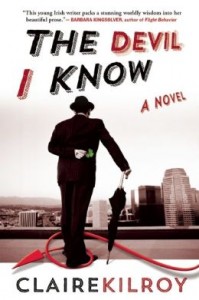

In this uniquely Irish combination of satire and morality tale, author Claire Kilroy introduces the young, alcoholic thirteenth Earl of Howth, who is testifying in a 2016 legal case about the “Celtic Tiger” and the Irish real estate “bubble” from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, a case in which he was an active, but naïve, participant. Fueled, in part, by the investments of shadowy foreign moguls, who often provided the seed money for grand schemes in which hundreds of hopeful Irish businessmen contributed additional, usually borrowed, funds, the real estate frenzy featured gigantic construction projects on large swathes of land cleared and stripped for hotels, apartments, housing complexes, and commercial use. Then, in 2008, the “bubble” burst, bringing down the Irish economy, banks, investment companies, and most of those individuals who had invested their hard-earned, inherited, or borrowed funds in schemes which ultimately left them penniless, their personal property gone, and their lives in shreds. Many well known financiers and bankers were shown on television doing the “perp walk” as police led them from their now bankrupt companies.

In this uniquely Irish combination of satire and morality tale, author Claire Kilroy introduces the young, alcoholic thirteenth Earl of Howth, who is testifying in a 2016 legal case about the “Celtic Tiger” and the Irish real estate “bubble” from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, a case in which he was an active, but naïve, participant. Fueled, in part, by the investments of shadowy foreign moguls, who often provided the seed money for grand schemes in which hundreds of hopeful Irish businessmen contributed additional, usually borrowed, funds, the real estate frenzy featured gigantic construction projects on large swathes of land cleared and stripped for hotels, apartments, housing complexes, and commercial use. Then, in 2008, the “bubble” burst, bringing down the Irish economy, banks, investment companies, and most of those individuals who had invested their hard-earned, inherited, or borrowed funds in schemes which ultimately left them penniless, their personal property gone, and their lives in shreds. Many well known financiers and bankers were shown on television doing the “perp walk” as police led them from their now bankrupt companies.

Summoned to court years later, Tristram St. Lawrence gives evidence for ten days between March 10, 2016, and March 24, 2016, his whereabouts a mystery from the time of the real estate crash to the much later trial. Though he was personally involved in several enormous real estate schemes during the height of the action, he was, from the outset, a front man – a figurehead whom M. Deauville, a mysterious foreign investor, chose for his noble background and the presumed legitimacy his title would bestow on the projects being undertaken by Castle Holdings, domiciled in the thousand-year-old castle in Howth owned by Tristram’s father. M. Deauville, a man so secretive that Tristram does not even know his first name, first met Tristram when he sponsored him for Alcoholics Anonymous, and he remained constantly in touch with him, even after Tristram’s return to Ireland from Europe and America in the 1990s. Eventually M. Deauville, whom Tristram regards as his “savior,” involved Tristram in Irish real estate investments, actively pulling the strings promoting future developments and sending Tristram and his construction manager, Desmond Hickey, to investigate new properties, even as the first mega-projects were just getting started.

By combining the satire with morality tale, author Claire Kilroy is able to present Tristram’s story in a style which highlights Tristram’s almost cartoon-like vulnerability and his own role in his downfall. Though no reader will take Tristram seriously, most readers will be empathetic as they recognize how he is manipulated on his step-by-step journey to disaster. To give Tristram some credit, even he becomes alarmed, at one point, because “across the country people were digging themselves into big holes, [and because] big holes were spreading across Ireland like the pox, eating away at the heart of Ireland,” but he also believes that his own doubts “were the product of a depressive mind.” He remains involved in the various schemes, a weak man who sees this as an opportunity for quick success.

As the frenzy of speculation continues, the lively action also reveals the character and behavior of everyone surrounding Tristram. Desmond Hickey, the crude construction manager, will not take no for an answer and insists that alcoholic Tristram accept a pint when they first meet at a pub. It is only “divine intervention” in the form of a cellphone call from M. Deauville that keeps Tristram from succumbing to the temptation. The energetic Hickey is soon proposing another development plan – for an abandoned castle and all its lands, and when Tristram visits the place, he has an epiphany of sorts. “A moth-eaten oul pony” living in the wilderness comes out from the bushes, and Tristram recognizes him as “Prince,” a childhood pet. The scene, both sentimental and cautionary, also contains elements of religiosity which contrast with the crass behavior of Hickey and Tristram to date. “I fear,” Tristram observes, ironically, “that every blessed thing on this earth is cursed with the capacity to wonder at its predicament – Prince was left wondering what he’d done wrong. His offense must have been egregious to be abandoned like this. It had started out so well.”

As the book satirizes the weaknesses of Tristram and others involved in the greed and manipulation, the author overtly ties their “sins” to a kind of competition between good and evil, between a higher power and “that other fella,” at least in Tristram’s mind. When he and Desmond Hickey are sent to investigate yet another possible development site, they both become convinced that “the end is near.” In “the black hole” of the countryside, one dark night, Dessie confesses to feeling the Devil breathing down the back of his neck – and sitting in the back seat of his truck. Suddenly Tristram feels it, too, though they both realize that the truck has no back seat. The novel’s conclusion extends the morality tale, tying up loose ends of plot, including some obvious religious imagery, and tightening the overall thematic development of the novel. Though author Claire Kilroy begins this tale with a quotation about a “Sir Tristram” in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, she ends it, appropriately, with the dark adaptation of a nursery rhyme: “There was a crooked man and he walked a crooked mile./ He made a crooked deal and he blew a crooked pile./He dug a crooked hole and he sank the crooked isle./And they all went to hell in a stew of crooked bile.” Entertaining and enlightening.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

Howth Castle has belonged to the St. Lawrence family since the time of the Vikings. Photo from http://www.goldenireland.ie

Gaffney’s Summit Inn, where Tristram St. Lawrence and Desmond Hickey first meet, may be seen here: http://www.thesummitinn.ie/

The photo of the Criminal Court of Justice in Dublin may be found on http://www.courts.ie/