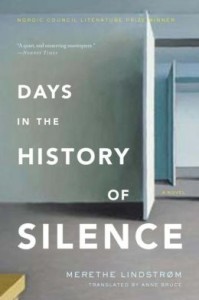

Note: This book was WINNER of the Nordic Council Literature Prize and WINNER of the Norwegian Critics’ Prize for Literature.

“Several times I have remained standing in the parking lot [of the adult daycare center], like a mythological figure filled with doubt, this is the border between the underworld and our own world…I need to tell this to someone, how it feels, how it is so difficult to lie with someone who has suddenly become silent. It is not simply the feeling that he is no longer there It is the feeling that you are not, either.”—Eva, Simon’s wife.

This is one of the most memorable books I have read in many years (and I can count on one hand the times I have said that in a review). Breath-taking in its emotional impact, insightful in its depiction of the main character and themes, and completely honest, the book left me weeping in places and silently begging the main character not to make some of the choices that I knew she would inevitably make. Eva, an ordinary, elderly woman with a now-silent husband, ten years older, tells her own story, with all the hesitations, flashbacks, regrets, and questions which are tormenting her now and which have confounded her husband. In creating Eva, Norwegian author Merethe Lindstrom has brought to life one of the most vividly depicted characters I have ever “known,” a character filled with flaws, like the rest of us, prone to second-guessing, like the rest of us, and sometimes overcome with regret for past mistakes, like the rest of us, and she does this without any hints of authorial manipulation in Eva’s story, which feels as if it is emerging of its own will from Eva’s depths. More reminiscent of a memoir than fiction, Eva’s story ultimately offers much to think about, while offering its own silent commentary on the choices we make and how they affect those around us.

This is one of the most memorable books I have read in many years (and I can count on one hand the times I have said that in a review). Breath-taking in its emotional impact, insightful in its depiction of the main character and themes, and completely honest, the book left me weeping in places and silently begging the main character not to make some of the choices that I knew she would inevitably make. Eva, an ordinary, elderly woman with a now-silent husband, ten years older, tells her own story, with all the hesitations, flashbacks, regrets, and questions which are tormenting her now and which have confounded her husband. In creating Eva, Norwegian author Merethe Lindstrom has brought to life one of the most vividly depicted characters I have ever “known,” a character filled with flaws, like the rest of us, prone to second-guessing, like the rest of us, and sometimes overcome with regret for past mistakes, like the rest of us, and she does this without any hints of authorial manipulation in Eva’s story, which feels as if it is emerging of its own will from Eva’s depths. More reminiscent of a memoir than fiction, Eva’s story ultimately offers much to think about, while offering its own silent commentary on the choices we make and how they affect those around us.

Eva, the mother of three daughters by her husband Simon, is also the mother of a son, born when she was an unmarried teenager and whom she gave up for adoption when he was six months old. Though she does not regret that decision, she does regret the loss, and she often wonders about her son and his fate. Whether by circumstance or design, Eva has few friends, often shunning intimacy, even with her own children, and though she eventually becomes a teacher of language and literature, she is constantly aware that the school is “rooted in its own convictions” and that she herself is probably superfluous to its success. Now retired, she admits that “I do not know if I miss the work, but I wish to be part of something, I always have the feeling of being left out, standing on the outside.” She and Simon see their grown daughters only “now and again,” and their former colleagues and acquaintances “from time to time…That was long ago.”

Simon, a former physician, sometimes used to meet her for lunch or coffee during her free periods at school, when his appointment schedule allowed, but he is long retired. At first they both enjoyed retirement, but Eva notes, “His gradual change started a couple of years ago…Perhaps his restlessness was present long before that, maybe it is an expression of something he has wanted for a long time To go his own way.” Gradually, he has become almost silent, and Eva is now forgetting the sound of his voice. “He has become as formal as a hotel guest, seemingly as frosty as a random passenger you bump into on a bus.” And he has begun to wander alone, out of the house, often sitting on a bench in the garden outside the Natural History Museum for hours, even in winter. Though she takes him to a daycare center two days a week, her daughters feel that he now needs full-time care, and they have left an application with her.

In the winter Simon would sometimes sit for hours in the garden of the Museum of Natural History

From this point on, the novel becomes the stories of Simon and Eva in the past. Their stories swirl around through Eva’s memories, shared with the reader in an order which feels random but which the author has subtly planned for dramatic effect. Always, there are questions about what happens next in their earlier lives and how and why, though the answers to these questions by no means constitute a plot in the usual sense of the word. Simon’s life in central Europe during World War II and its aftermath; their more recent three-year relationship with Mariya, a Latvian asylum-seeker in Norway, whom Eva and Simon hired as a house cleaner and who became Eva’s intimate friend; the young intruder who entered their house years ago when Eva and her pre-school children were alone; Simon’s need for family and his pervading sorrow about the past; their shared resentments; the attitudes of their daughters toward some of their decisions; and Eva’s attempts to assuage the guilt she feels about secrets in her own life, all appear and reappear through memories which increase the reader’s knowledge about Eva and Simon.

Much of the novel feels like a canon in music, with motifs appearing, being superseded by other motifs, then reappearing, almost like a round. Winter brings its own obvious imagery and symbolism related to aging, life, and death. Eva sometimes walks by a church and gradually comes to know the pastor there, though there is  no overt religious symbolism or reference to an afterlife. A mailbox given, significantly, by Mariya, brings letters bearing news of both the past and present. Eva’s commitment to decorating a grave of someone she does not know, and a large snail shell (minus the snail) which she finds in one of her closets also raise questions about life and death and memories and home, and add to the symbolism as images reappear and add to the characterization and the vibrant inner lives of Eva and Simon. The emphasis on winter eventually changes to that of spring and then summer, suggesting the possibility of change.

no overt religious symbolism or reference to an afterlife. A mailbox given, significantly, by Mariya, brings letters bearing news of both the past and present. Eva’s commitment to decorating a grave of someone she does not know, and a large snail shell (minus the snail) which she finds in one of her closets also raise questions about life and death and memories and home, and add to the symbolism as images reappear and add to the characterization and the vibrant inner lives of Eva and Simon. The emphasis on winter eventually changes to that of spring and then summer, suggesting the possibility of change.

Though this is one of the most memorable books I have read in years, it will not appeal to everyone. (Take a look at the Amazon reviews for examples.) This is a character-based novel, with little or no overt plot, and those expecting a “Joe [sic] Nesbo book” because of its Norwegian setting, as one Amazon reviewer confessed, will be disappointed. Ditto for those who want a straightforward narrative, a love story, and/or a story about people who are younger than “elderly.” For those who have dealt intimately with older family members with memory problems, or those who are senior citizens themselves, however, this is a powerful, emotional, and never-to-be-forgotten novel of pure honesty and literary skill.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Johannes Jansson/Norden.org appears on http://en.wikipedia.org

The Natural History Museum garden in Oslo in winter is from http://www.irisbg.com

The photo of the hands, both elderly and young, is part of a program on aging presented by http://www.wbur.org