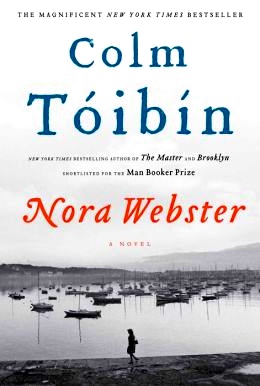

Note: Colm Tobin was WINNER of the IMPAC Dublin Award, the biggest award in literature in 2006, for THE MASTER, and he was WINNER of the Costa Award for BROOKLYN in 2009. He was SHORTLISTED for the 1999 Booker Prize and for the 2001 IMPAC Dublin Award for BLACKWATER LIGHTSHIP. He is NOMINATED for the 2014 Costa Award for Fiction for this book.

“It was done. In her all-embracing glance around the room, Mrs. Darcy [Nora’s neighbor] had made it all seem real. Nora would leave this [summer cottage] and never come back. She would never walk these lanes again and she would let herself feel no regret. It was over. She took up the few things she had collected and put them in the boot of her car.”

Nora Webster, recently widowed in her mid-forties, has decided to sell the now-deteriorating country cottage on the Irish coast in Cush, where her family has spent summers for many years. Her drive to the Irish seaside to clean out the property is one she makes alone, leaving her two young sons in the care of others while she works. Reminiscing about the past, her beloved husband Maurice, and the family vacations there over the course of twenty years, she realizes that her daughter Fiona, now in college, will be especially saddened by the loss of the cottage, and that her own two little boys, Donal and Conor, will miss their friends there. With her whole life at loose ends, she has not yet told her older daughter Aine, who is living in Dublin, about the need to sell the cottage for financial reasons, and she regrets her lack of connection and her behavior toward her children during the months in which Maurice was dying. She feels guilty because she has not been able to comfort Fiona with some personal remarks wishing her well in school and actually showing her that she loves her. As for her two young sons, who were being cared for by her Aunt Josie for two months, she cannot help noticing that their attitude toward her has changed significantly during Maurice’s illness and eventual death, and “she felt she would never be sure of them again.”

Nora Webster, recently widowed in her mid-forties, has decided to sell the now-deteriorating country cottage on the Irish coast in Cush, where her family has spent summers for many years. Her drive to the Irish seaside to clean out the property is one she makes alone, leaving her two young sons in the care of others while she works. Reminiscing about the past, her beloved husband Maurice, and the family vacations there over the course of twenty years, she realizes that her daughter Fiona, now in college, will be especially saddened by the loss of the cottage, and that her own two little boys, Donal and Conor, will miss their friends there. With her whole life at loose ends, she has not yet told her older daughter Aine, who is living in Dublin, about the need to sell the cottage for financial reasons, and she regrets her lack of connection and her behavior toward her children during the months in which Maurice was dying. She feels guilty because she has not been able to comfort Fiona with some personal remarks wishing her well in school and actually showing her that she loves her. As for her two young sons, who were being cared for by her Aunt Josie for two months, she cannot help noticing that their attitude toward her has changed significantly during Maurice’s illness and eventual death, and “she felt she would never be sure of them again.”

Throughout much of this intense character study by Colm Toibin, which takes place in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Nora Webster observes the niceties – common, traditional actions which give her a way to deal with reality without thinking too much – and since she is reluctant to share her feelings directly with anyone, it is up to the reader to figure out her inner needs and moods by observing her behavior. The author “takes the reader to school” here in terms of his ability to develop Nora’s character without resorting to overt explanations of her thoughts and moods, and he controls our perceptions of Nora without using emotionally charged adjectives like “frenzied” or “cold,” or adverbs like “regretfully,” or “angrily” to describe her behavior for the reader. He is confident that the reader will be able to understand Nora simply by observing her in her life. If Nora’s story itself were not so compelling on the face of it, one might almost describe its style as journalistic – factual and observant, with no agenda, despite the many domestic scenes as Nora and her family live their lives. Through vibrant, often touching, scenes in which the characters speak and interact, seemingly on their own, Toibin draws in the reader so subtly that one never feels manipulated, the quiet development appropriate for the character of Nora herself – reserved, unassertive, and uncertain about the future. She is a person who has, in her shy unwillingness to take charge, unwittingly hurt and perhaps damaged some of those she loves most, largely through her misperception that being stubborn is the same as being strong.

Charley Haughey, Irish Minister for Finance, and Neil Blaney, Minister for Agriculture and Fisheries, at their trial for sending arms to Irish partisans in Northern Ireland in 1970, a political crisis which takes place as Nora grieves.

Nora’s boys have returned from their stay at Aunt Josie’s house during their father’s final two months with obvious problems and a sense of loss – Donal is stuttering, and Conor is wetting the bed – but Nora sees her primary duty to be that of finding a job to ease the family’s financial burdens after Maurice’s death, and when she does, it is a full-time job which leaves her precious little time to spend reconnecting with the boys, a problem she excuses as a necessity. Her boss in her new job, a former schoolmate whom she and her friends always disliked, regards her position over Nora as sweet revenge, and she makes life for Nora as difficult as possible over the course of a year. A crisis leads to Nora’s taking a stand for the first time, and the boys ultimately benefit from it as she gradually becomes stronger and more independent and realizes that she does not necessarily have to remain a victim.

Father Edward Daly, waving a blood-stained white handkerchief as he escorts a mortally-wounded protester to safety during the events of Bloody Sunday (1972) in Derry, Northern Ireland, another event which takes place during this novel. Photo by John Bierman

Nora’s behavior parallels some of the social and political movements of Ireland in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time in which Ireland was roiling with deeply emotional issues – the establishment of unions, the second class status of women, the Irish Republican Army’s attacks in Northern Ireland, the widespread arrest of Catholics in Protestant Derry to the north, and the Arms Crisis involving the transportation of arms from Ireland to rebels in Northern Ireland by two Irish government ministers in 1970. Despite the unfolding of these dramatic national events, however, the focus of the novel still remains clearly on Nora and her acts of personal disobedience, with the national events being primarily part of the atmosphere. When Nora ultimately challenges a priest who changes Conor’s school classroom, she makes a major statement psychologically, and she is feeling strong and confident by the time Bloody Sunday occurs in Derry, where twenty-six unarmed Catholic civilians are killed during a demonstration. The burning of the British Embassy in Dublin in 1972 takes place a few days later, in retaliation. Generational differences are highlighted by the activities of Nora’s daughter Aine, who is deeply involved in these political causes and seemingly has no fear.

A few days after Bloody Sunday in Derry, N. Ireland, the British Embassy is burned in Dublin, another event affecting Nora peripherally. Double click to enlarge, then scroll.

Adding softness to the hard psychological truths which Nora must face before she becomes comfortable in her take-charge mode is her love of music and her decision to spend more time with it, a decision which leads her to grow emotionally as she studies voice, collects recordings, and spends hours listening to music on the phonograph, sometimes feeling as if she has merged completely with the music itself. And when, near the end of the novel, she decides also to redecorate her house, she has a transformative experience which, because of her reticence throughout the novel, is both believable and poignant. An author at the zenith of his writing career, Colm Toibin does it all with this novel, as he introduces a tentative and unassertive woman and develops her into a real, fully rounded character who retains her flaws and but learns to manage them as she eventually creates a real life for herself and her family. This quiet novel will appeal to those who treasure precise and careful writing and admire an author’s ability to surmount the challenges of bringing a difficult character fully to life, however “ordinary” that life may be. Toibin’s literary talents shine brilliantly here.

ALSO reviewed here: Colm Toibin’s THE MASTER

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.thetimes.co.uk

The photo of Charlie Haughey, Minister of Finance, and Neil Blaney, Minister for Agriculture and Fisheries, during their trial for sending arms to rebels in Northern Ireland is seen on http://www.davidicke.com This event, like the other dramatic political crises here, take place during Nora’s grieving,

During Bloody Sunday, Jan. 30, 1972, Fr. Edward Daly is seen waving a handkerchief in order to get a mortally wounded demonstrator to help. http://en.wikipedia.org/

The headlines regarding the burning of the British Embassy in Dublin on Feb. 2, 1972, just a few days after Bloody Sunday, are shown on http://www.indymedia.ie This event also caused Nora come concern.