“Each family is fed by its secrets. Like a strangely bulimic climbing vine, the unrevealed secrets embrace the family’s flesh a little tighter each day, until in the end they become one with it. You can’t tell the vine from the flesh. A couple joined for all time, and if you try to pry it apart, you destroy it.”

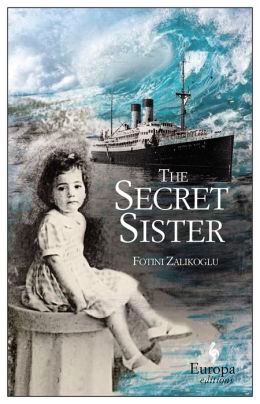

Greek author Fotini Tsalikoglou, in her first novel to be translated into English, introduces a man we come to know as Jonathan, along with the first of his family’s many mysteries. Jonathan has just boarded a plane from New York City to Athens, and while sitting next to an empty seat in the plane, he speaks to it as if it were “Amalia,” his sister. He is remembering an unnamed woman who dragged him, as a small child, to museums all over New York to see Greek statues and pediments, but who never had any interest in going to Greece herself. He is puzzled because, despite this behavior toward Greek art, she was clearly “revolted by her country.” Her name was Lale Andersen, a name she chose when she changed it from the original, and she was Jonathan’s “mutant mother.”

Greek author Fotini Tsalikoglou, in her first novel to be translated into English, introduces a man we come to know as Jonathan, along with the first of his family’s many mysteries. Jonathan has just boarded a plane from New York City to Athens, and while sitting next to an empty seat in the plane, he speaks to it as if it were “Amalia,” his sister. He is remembering an unnamed woman who dragged him, as a small child, to museums all over New York to see Greek statues and pediments, but who never had any interest in going to Greece herself. He is puzzled because, despite this behavior toward Greek art, she was clearly “revolted by her country.” Her name was Lale Andersen, a name she chose when she changed it from the original, and she was Jonathan’s “mutant mother.”

What follows is a complex conversation in which two people, Jonathan and Amalia, through changing times and places, discuss with each other their shared childhoods and differing memories. At one point, they also address a woman who served their grandparents, and at another point their grandmother herself provides her long personal story which details the family’s secrets. The author’s use of italics to set off one speaker from the other is helpful, as Jonathan remembers his Grandpa Menelaos and Grandma Erasmia, their emigration from Greece to New York, and his own life as a boy without a father. The novel jumps around without warning, as he comments to himself about the plane trip and his decision to travel to Greece, interspersing observations in the present with memories from his past, including the sometimes bizarre events which have made a lasting impression upon him from his childhood, including one in which he believes he has met his lost father.

Jonathan’s present goal is to reach the Holy Rock of the Acropolis, which Freud described in 1903, after putting on a clean white shirt for the occasion: “the amber color of the columns at twilight…[is] the most beautiful thing in the world.” Amalia insists that Jonathan, too, will one day put on his own clean white shirt, and that he might even hear the sound of the waves at the Acropolis, if the wind is right, a comment with symbolic connotations. Eventually, Jonathan dreams of Greece: “You, lost motherland of mine, so far away/ You’ll become a caress and a wound/ When Day breaks in another land…” He dreams, too, of happiness, believing that “Now I’m flying to life’s celebration/ Now I’m flying to the feast of my joy.”

The attack and fires by Turks on Smyrna in 1922 led to the death or emigration of up to 400,000 people.

The lives of Jonathan’s family unfurl during his reminiscences, and include the story his grandmother tells him about life in Cappadocia (in Turkey) and how she and her sister, ages seven and five, escaped the Ottoman army’s attack on nearby Smyrna in 1922. Jonathan’s grandmother and her sister, despite their young ages, eventually made their way to Greece, and as World War II broke out, years later, they married and came to New York, where Jonathan’s mother was born and later brought up two children alone – their father is never revealed. Ultimately, the novel becomes Jonathan’s story, and this past haunts every aspect of it.

The narrative, which is not really a narrative but a series of brief reminiscences by Jonathan, Amalia, and their grandmother, requires the reader to pay careful attention to the text as it explores the complex meanings of identity and the importance of the past in determining one’s future. Because it is so short (only 116 pages), and so limited in its exploration of the background of the several characters, the reader must depend on the author (and translator, Mary Kitroeff) for the context clues which explain Jonathan’s journey, reveal his state of mind as he begins it, and justify his need for Amalia as a “companion” on the journey. For some readers the information provided here may not be enough to make the main character’s decision to go to Greece feel like the natural, inevitable outgrowth of his experience, or make the ultimate fates of two other characters feel inevitable. For others, the sense of continuity with the past will be rewarding.

Jonathan, his mother, and sister lived at this address on the Upper West Side, overlooking the Hudson River.

The writing is compressed, psychological, and filled with the mysteries of life both in the present and in the past, and how much influence these mysteries may have on the main characters is suggested, rather than stated. Some readers may diverge from the author’s suggestions that we cannot escape the past – that we become who we are by the accidents of fate. Others may feel that we have more control over the present than what we see in the lives of Jonathan and Amalia. Many tantalizing questions remain as the novella comes to a close. Readers looking for a change of pace and an analysis of how much we may all be connected to and controlled by family secrets will find this novella a treasure trove of suggestions, though readers will have to draw their own conclusions. Ultimately, when Amalia talks in the conclusion about Greek composer Manos Hadjidakis writing a song for the original Lale Andersen, “The North Wind Came, the South Wind Came,” the reader will look carefully at the lyrics as a way to understand more fully the ideas of this novella, ideas that Jonathan develops in the conclusion as he gets off the plane in Athens: “What existed doesn’t exist anymore. But you only die when you cease to remember the ones you love. You die when your homeland shifts places on the map. It’s a good land that waits for me there,” a statement which opens as many questions about identity as it answers.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://groessenwahn-verlag.de

The Holy Rock of the Acropolis at twilight, when Freud said the pillars looked like amber, may be found here: http://www.discovergreece.com/

The escape by many residents of Cappadocia and Smyrna, Turkey, during the Turkish attack and fire in 1922, is found on http://www.helleniccomserve.com

As children, Erasmia and Frosso often played in the Fairy Caves of Cappadocia, Turkey: http://www.wildjunket.com

Lale Andersen, Jonathan, and Amalia lived on the Upper West Side, near the Hudson River, at this address. http://www.elliman.com/

ARC: Europa Editions