Note: Damon Galgut was WINNER of a Commonwealth Writers Prize in 2003. Both The Good Doctor (2003) and In a Strange Room (2010) were SHORTLISTED for the Man Booker Prizes in the years of their publication.

“His writing felt to him light, insubstantial. He did not have the weight, he thought, to measure up to his themes. He was writing about money and power, among other things, and he bumped up every day against the thinness of his knowledge. Always he ran aground on the edges of what he knew, and found himself beached in ignorance. And here again was the old question of marriage, and the way that men and women behaved together. What could he say about these things?”

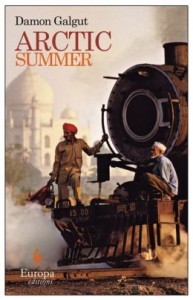

South African author Damon Galgut’s fictionalized biography of author E. M. Forster (1879 – 1970), known as Morgan, takes a different approach from non-fictional biographies, synthesizing all the author’s research into the character of Forster and then journeying inside his mind, ultimately allowing “Forster” to tell his own story. As the openly gay Galgut emphasizes throughout this novel, Forster’s most significant difficulty in his personal life and in his writing seems to have been in reconciling his homosexuality with the rest of his life so that he could live and love fully on all levels. During Forster’s most prolific years as a novelist, 1908 – 1924, “minorite” activities were almost universally hidden – not just frowned upon by society, but rejected as aberrant behavior.

South African author Damon Galgut’s fictionalized biography of author E. M. Forster (1879 – 1970), known as Morgan, takes a different approach from non-fictional biographies, synthesizing all the author’s research into the character of Forster and then journeying inside his mind, ultimately allowing “Forster” to tell his own story. As the openly gay Galgut emphasizes throughout this novel, Forster’s most significant difficulty in his personal life and in his writing seems to have been in reconciling his homosexuality with the rest of his life so that he could live and love fully on all levels. During Forster’s most prolific years as a novelist, 1908 – 1924, “minorite” activities were almost universally hidden – not just frowned upon by society, but rejected as aberrant behavior.

Strict codes of behavior governed how people interacted within various social classes, and the need to conform allowed little room for any kind of social experimentation and led to the ostracism of those who were “different.” How “minorites,” in particular, came to terms with their essential natures and were able to live within this restricted society becomes a major theme of this novel.

The novel opens in 1912 after the success of Forster’s first three novels – Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905), The Longest Journey (1907), and A Room with a View (1908), and Forster is on his way to India for the first time. Six years earlier, he’d been living in Surrey with his mother when he was asked if he would tutor a seventeen-year-old student from India, Syed Ross Masood, a young man who needed Latin tutoring before he went to Oxford. Over the next five years, the young man steals Forster’s heart, though Forster remains outwardly “paternal” toward him. Masood, in turn, finds Forster “like family to him.” All through Masood’s college years, they share a deep friendship, and Masood instinctively recognizes that Forster is different from most Englishmen: “From the very first moment I met you, I knew that here was an Englishman who didn’t see the world like the rest of his countrymen. You don’t realize it, but you have an Oriental sensibility. That is why the book you’ll write will be unique.” Masood wants him to write a novel about the English in India (A Passage to India), a novel which does not take form for more than a dozen years.

After this introduction, the novel divides into three parts and a conclusion—Forster’s six-month trip to India after Masood returns home, his three years in Egypt working for the Red Cross during World War I, another trip to India, and the conclusion in which he describes writing his final novel, A Passage to India. Throughout the novel, Forster looks for companionship and sees friends, some of them from the Bloomsbury group who share his minorite proclivities and remain isolated from society. Many of these almost certainly gay friends eventually marry for self-protection.

Kailasa Cave #16, with its elephants, “seen in the last bloody rays of the sun.” It was excavated and built from the top down from a single piece of rock.

The first trip to India, during which time Masood has provided Forster with a guide, opens his eyes to spiritual and aesthetic feelings that he has not had in England. From Buddhist caves and shrines which he sees from the back of an elephant, to the elaborate Humayan’s tomb (which resembles the Taj Mahal in design), and to the Barabar caves used by ascetics, Forster’s world opens, even as his time with Masood is scarce. A meeting with the Maharajah of Chhatarpur at his palace and with the Rajah of Dewas expand his vision, one that is epitomized later in Ellora with his vision of the Kailasa cave “seen in the last bloody rays of the sun.”

Edward Carpenter and friends in front of Millthorpe Cottage, Sheffield. Carpenter lived openly with his male partner and challenged the mores of the day.

Back home again in England before leaving for Egypt, Forster sees Ted Streatfeild, Edward Carpenter (who lives openly with a man and refuses to hide his status), Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (Goldie), Lytton Strachey, Alec Scudder, D. H. Lawrence, and others, names dropped into the novel and adding some color and atmosphere but little direct insight into the prevailing literary scene. Only Leonard Woolf seems to have a direct involvement with Forster’s issues regarding his writing. No matter where he is, India, Egypt, or England, Forster is seeking love, and when he finds it, the reader wants to cheer. The novel, as a novel, is superb, with a main character who appears to open his life to the reader and share his feelings. The descriptive scenes and the dialogue bring much of the exotic setting to life, though at times Forster’s travels have the flavor of a travelogue. Still, few readers will be able to forget the agony that colors Forster’s life and the writing of his novels.

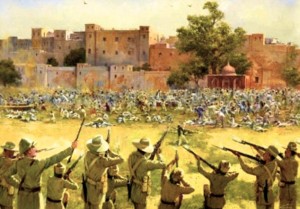

The Amritsar Massacre in which many hundreds of unarmed citizens engaging in a protest were killed by the British became a rallying point against British colonial rule in India in 1919.

Where I part company with many other reviewers is on a more abstract plane, beginning with the question of why the author wrote this novel in the first place. While it is an excellent novel on all literary grounds, I am uncomfortable with the idea of one person, author Damon Galgut, presuming to “become” another person, E. M. Forster, and telling an audience all the intimate details of what Forster is feeling at any given moment – from Forster’s point of view. Though Forster kept a diary and wrote many letters, he chose not to reveal his inner conflicts publicly or in his own writing. His novel Maurice, in which he wrote about same-sex love in England in 1913, revising it twice over the next fifty years, was left unpublished until after his death, and though it was published and eventually made into a film and a play, Forster himself uses characters named Maurice Hall and Alex Scudder, not E. M. Forster and his unnamed great love. Perhaps it is my own sense of privacy which is offended by this seeming invasion of Forster’s own well deserved privacy – and not because of the subject matter. To me, this feels too much like the “celebrification” of a private person who has deliberately chosen to remain private during his own lifetime.

The fact that Galgut also publishes this novel under the title of Arctic Summer, a novel which Forster himself never finished or published, suggests that he may actually see himself standing in Forster’s shoes as he publishes this book with its ironic title. That’s a blurring (if not crossing) of the line between reality and fantasy which leaves me wondering about the future of “fictionalized” biographies, at least those in which the subject is identified throughout by a real, not fictionalized, name. Ultimately, I wonder how much of an author’s life is “fair game” for biographical novels if the author himself chose to keep his own secrets unpublished.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.dailymail.co.uk.

Forster with his friend Masood in India is shown on http://www.outlookindia.com/

The Kailasa Cave #16 is from http://www.world-mysteries.com/ “The Kailasa Cave #16 is a remarkable example of Dravidian architecture on account of its striking proportion, elaborate workmanship, architectural content, and sculptural ornamentation of rock-cut architecture. The temple was commissioned and completed between dated 757-783 CE.” (Wiki) These cave constructions were created from the top down, excavated from ground level downward in the eighth century.

Edward Carpenter in front of Millthorpe Cottage, Sheffield, a place where he was comfortable living with his male partner in contravention of the conventional “wisdom” and encouraged others to do likewise. http://www.picturesheffield.com/

The Amritsar Massacre of 1919 became a rallying point against British colonialism when hundreds of unarmed civilians were killed by nervous British soldiers. At the same time, a similar uprising was taking place in Alexandria, Egypt, presaging the end of colonial rule. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

ARC: Europa Editions