“Northern Europe is a place of cold light and clear lines…and so is Protestantism. The Mediterranean world is indomitable sunshine and impenetrable shade. So is Catholicism. Then this…this…numinous…Orient…its bells, its dragons, its millions…Here, notions of transmigrations, of karma, which are heresies at home, possess a…a…plausibility.”—Jacob de Zoet, Dejima, 1800.

David M itchell’s past work, full of literary excitement, has been almost universally lauded for its originality and experimentation, and two of his novels, number9dream (2001), and Cloud Atlas (2004) have been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Ghostwritten (1999) won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, and in 2007, Mitchell was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World. This novel will come as a surprise to many of his long-time fans. Here, Mitchell writes a historical novel—a HUGE historical novel—set in Nagasaki at the turn of the 19th century, when the Dutch East India Company was Nagasaki’s only trading partner. In an unusual change, Mitchell writes in the 3rd person here, taking an omniscient point of view which allows him to unfurl fascinating tales and re-imagine historical events in dense prose packed full of energy and local color. Using a straight chronology which begins in 1799 and ends in 1817, Mitchell introduces a young Dutch seaman who is trying to earn enough money to marry his Dutch sweetheart; a pioneering Dutch physician; a scarred Japanese woman who has become a brilliant midwife; a samurai magistrate; a venal Japanese abbot in charge of a home-grown monastery; an ape named William Pitt, and an assortment of dishonest traders as they engage in the hurly-burly world of Nagasaki trade.

itchell’s past work, full of literary excitement, has been almost universally lauded for its originality and experimentation, and two of his novels, number9dream (2001), and Cloud Atlas (2004) have been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Ghostwritten (1999) won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, and in 2007, Mitchell was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World. This novel will come as a surprise to many of his long-time fans. Here, Mitchell writes a historical novel—a HUGE historical novel—set in Nagasaki at the turn of the 19th century, when the Dutch East India Company was Nagasaki’s only trading partner. In an unusual change, Mitchell writes in the 3rd person here, taking an omniscient point of view which allows him to unfurl fascinating tales and re-imagine historical events in dense prose packed full of energy and local color. Using a straight chronology which begins in 1799 and ends in 1817, Mitchell introduces a young Dutch seaman who is trying to earn enough money to marry his Dutch sweetheart; a pioneering Dutch physician; a scarred Japanese woman who has become a brilliant midwife; a samurai magistrate; a venal Japanese abbot in charge of a home-grown monastery; an ape named William Pitt, and an assortment of dishonest traders as they engage in the hurly-burly world of Nagasaki trade.

The result is Mitchell’s most unusual novel. The Dutch East India Company, the only foreign presence allowed in Nagasaki, is confined to Dejima, a man-made island in the harbor. Only the higher officers may use the narrow, and guarded, bridge to the mainland. The Dutch traders are an often devious lot, trying to create personal fortunes by deceiving not only their Japanese hosts but the Dutch East India Company itself. To correct the undoubtedly fraudulent record-keeping, young Jacob de Zoet, a clerk in his mid-twenties, has been assigned to straighten out the books, a job which does not win him friends in Dejima, and he is not sure how many years he will have to stay there. The Netherlands, in economic decline, has come increasingly under the influence of the French; Prussia and Austria are threatening their borders; and the British have seized many of their colonies, conditions which some traders feel justify their taking whatever they can get for their personal use.

Many of the traders are no more civilized in their personal relationships than in their business dealings, as their treatment of the Spanish and African crew reveals, and Jacob de Zoet, though friendly with Dr. Marinus, forms his closest relationships are with the Japanese: Ogawa Uzaemon, an interpreter of the first rank, who is interested in reading de Zoet’s copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, and Abaigawa Orito, a woman whose face is scarred but whose brilliance has been recognized by Dr. Marinus, a physician and scholar who is training her in medicine. Together they provide de Zoet with a life, and he is soon in love with Orito. As in all epic novels, love is thwarted on several levels, and as Part I ends, honest Jacob de Zoet is at the mercy of his greedy fellow crewmen, remaining in Dejima as the Shenandoah, on which he arrived, leaves for Batavia loaded with goods.

Part II shifts the focus to the inhabitants of a remote monastery on Mount Shiranui, ruled by an abbot whose sadism knows no bounds. The women there, all poor, are imprisoned, forcibly impregnated and required to give their babies as “gifts” to the monastery. When Jacob de Zoet’s interpreter, Ogawa, hears what is happening there, he and a samurai friend set out to liberate the monastery, which allows Mitchell to explore other aspects of the culture, the samurai tradition, the changing loyalties of friends, and the difficulty of creating change in a traditional society in which connections to powerful people are the key to action.

Part II shifts the focus to the inhabitants of a remote monastery on Mount Shiranui, ruled by an abbot whose sadism knows no bounds. The women there, all poor, are imprisoned, forcibly impregnated and required to give their babies as “gifts” to the monastery. When Jacob de Zoet’s interpreter, Ogawa, hears what is happening there, he and a samurai friend set out to liberate the monastery, which allows Mitchell to explore other aspects of the culture, the samurai tradition, the changing loyalties of friends, and the difficulty of creating change in a traditional society in which connections to powerful people are the key to action.

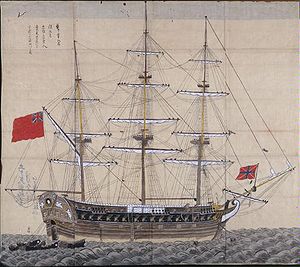

Part III brings the British into the trading equation. Dejima is occupied by only a handful of Dutch, since their ship has returned to Batavia, and the Japanese, accustomed to having only a small army to protect against the Dutch who are confined to Dejima, are helpless, their samurai scattered about the countryside and unable to return to the city on short notice. Flying a Dutch flag to disguise their intentions, the Phoebus enters under sail and tries to take over the port. Part IV, which takes place in 1811, and Part V, which takes place in 1817, continues the story of the Dutch traders who have remained in Japan and resolves the issues in their personal lives. Holland has fallen to Napoleon, and the Dutch East India Company is bankrupt.

Mitchell seems determined to give the reader absolutely everything s/he could want in a historical novel—an enormous cast of characters (many of them stereotypes), lively action, exotic settings, unusual events, struggles between good and evil, battles, tragedies, and even some humor. Setting the novel at a time in which both Japan and the west are experiencing major intellectual and political changes, he also deals with important themes—referring to new learning, new ideas, new weapons of warfare, new types of government, and new views of economics. Unfortunately, Mitchell does not develop all this smoothly and bring it all together. It’s a hodgepodge that keeps the reader hopping to stay abreast of what is happening and what is likely to happen next on many fronts at the same time. As hodgepodges go, however, it’s really, really good, and it does overcome some of its structural weaknesses by keeping the reader completely entertained.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, by Torsten Silz introduces a really good interview with the author: www.cbc.ca

The model of Dejima, with its one small bridge from the island to the mainland, is from the Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture: www.ltcm.net

Mitchell has compressed time a bit with the tale of the Phoebus. That episode is modeled on that of the HMS Phaeton, a British vessel which entered Nagasaki Harbor in 1808, under the Dutch flag, captured the Dutch welcoming party, demanded food and fuel, and took shots at other ships in the harbor before releasing their hostages and sailing away. This drawing is in the Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture. http://en.wikipedia.org