Note: Spanish author David Trueba was WINNER of Spain’s National Critics Prize in 2009 for his novel Learning to Lose. His film Living is Easy with Eyes Closed was WINNER of Goya Awards for Best Film, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay.

“Pivotal moments remain immortalized in your memory, associated with a circumstance, a detail, a place, a time of day. It was raining, you were wearing that sweater, a yellow car passed, a pigeon had been run over in the street. I didn’t want my breakup with Marta to get spattered with yogurt sauce. I would always associate the end of our romance with that kebab lunch in Munich; no further details necessary.” –Beto Sanz.

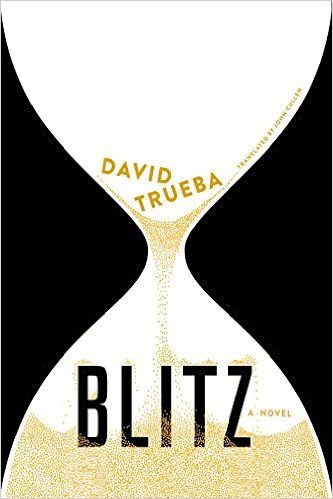

From the outset of this novel, author David Trueba’s ability to visualize and recreate intense word pictures dominates his style, making the reading of this novel a special treat on several different levels. Not only does he show the places and people surrounding his main character, Beto Sanz, instead of simply telling about them, but he also channels Beto’s own inner thoughts, providing lively commentary on virtually every aspect of his life and the activity around him. As the narrative opens, Beto has just arrived in Munich from Madrid for a conference for landscape architects, where his firm is a finalist for an international prize. His project is competing in the category of “landscape intervention, not necessarily feasible or reasonable…[but] something like a fantasy or a fiction.” Beto’s particular innovation is a “forest of human-sized hourglasses…sand clocks, which if you turned them over, accorded you a measured period of time to devote to your own thoughts…a reminder and quantifier of time, but also…an escape.” He is nervous but full of hope as he prepares for his presentation to the jury, after which he and Marta, his partner and lover, will return immediately to Spain.

From the outset of this novel, author David Trueba’s ability to visualize and recreate intense word pictures dominates his style, making the reading of this novel a special treat on several different levels. Not only does he show the places and people surrounding his main character, Beto Sanz, instead of simply telling about them, but he also channels Beto’s own inner thoughts, providing lively commentary on virtually every aspect of his life and the activity around him. As the narrative opens, Beto has just arrived in Munich from Madrid for a conference for landscape architects, where his firm is a finalist for an international prize. His project is competing in the category of “landscape intervention, not necessarily feasible or reasonable…[but] something like a fantasy or a fiction.” Beto’s particular innovation is a “forest of human-sized hourglasses…sand clocks, which if you turned them over, accorded you a measured period of time to devote to your own thoughts…a reminder and quantifier of time, but also…an escape.” He is nervous but full of hope as he prepares for his presentation to the jury, after which he and Marta, his partner and lover, will return immediately to Spain.

Later that day, while he is waiting to pick up a lunch order at a restaurant, Beto, in typical fashion, is maundering to himself about cell phones and vibrations and whether phones are harmful addictions; whether they will bring about deaths, million-dollar judgments, and detox clinics; and even whether they cause hyperactivity in children. Suddenly, the phone in his pocket vibrates with a text message: “haven’t told him yet, it’s really hard. argh. I [heart] u.” When he looks back at the table where Marta is sitting, he can “see from her expression that she’d sent [him] the text by mistake.” She has sent her message, meant for her current lover, to Beto instead. “Marta’s past had returned, elbowing my future right off the track,” Beto concludes. Some stubborn force prevents him from “stooping to recriminations,” but the next day Beto remains in Munich while Marta returns Madrid.

Allianza Arena, the soccer/football stadium in Munich, designed by Pierre de Meuron and Jacques Herzog, holds no interest for Marta.

What follows is the intimate story of one calendar year from January, when Marta and Beto end their relationship, through December, when Beto begins to take some control of his life. His is a long story of inaction and of doing what seems right at the time without any serious contemplation of the future. The author, a well-regarded film maker, allows the reader to share Beto’s innermost thoughts and experience some of his questionable activities, while he also uses visual elements from art and architecture to ground Beto’s life in a greater reality. It is up to the reader, however, to see relationships between the author’s choice of details and Beto’s inner life, since the author never becomes didactic, preferring to maintain the “tragicomedy” of Beto’s behavior without offering commentary. In one of the earliest artistic references, Helga, a woman in her sixties who is volunteering for the conference, picks up Beto and Marta at the airport and points out the Allianza Arena, the Munich soccer/football stadium, world famous for its architecture. Beto comments to Marta about the architects, but “she didn’t seem very interested,” a strange attitude considering the imposing architecture, the fact that it is the first stadium in the world to have a full color changing exterior, and the fact that she is his business partner in a company that celebrates architecture and landscape architecture.

Beto’s later decision to stay in Munich after the breakup, while Marta returns home, leaves him without a place to stay. Helga, the kindly, older woman who has picked them up at the airport, offers to let him stay at her apartment overnight until he can make new arrangements for his trip home. There he is impressed by an enormous poster for F. W. Murnau’s film The Last Laugh (1925) on her living room wall. In that film, an elderly man who lives a very simple life in near poverty, works his heart out as a doorman for a hotel and is proud of his work, fully living up to the impression his elegant uniform creates. When the old man, getting weaker with age, is demoted to washroom attendant, losing his uniform in the process, he loses his sense of identity and all his pride. Helga, the woman who has displayed this poster on her living room wall, is a practical and thoughtful woman with an inherent sense of pride, a characteristic we see during lessons she subtly illustrates to Beto during his visit. Beto is clearly a man with hopes but little sense of pride – and no real resources for taking charge of his life.

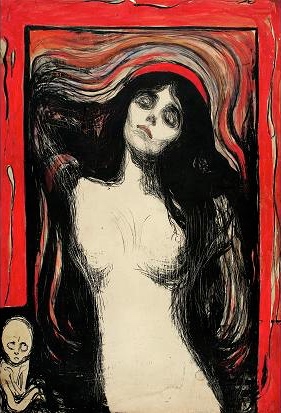

Also in Helga’s living room is a postcard of a reproduction of Edvard Munch’s Madonna, which also arouses strong feelings in Beto: “I felt like that monstrous infant in the corner of the painting, a fetal Baby Jesus, gazing neurotically at the ethereal beauty of his mother,” perhaps suggesting, on some level, his attitude toward the kindly Helga.

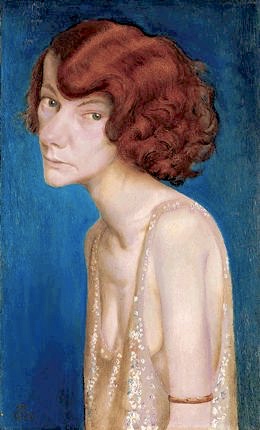

Later, on a tour of Munich before he returns to Madrid, Beto sees a sign for a small exhibition of paintings by Otto Dix, and he and Helga observe “the frightened, imperfect, spent, and fragile” women Dix painted, all considered “Degenerate Art” by the Nazis. Several of these paintings are included in this book, and though Helga finds the paintings disgusting, Beto is not so sure, another example of his lack of commitment, empathy, and serious thought.

In the second half of the novel, Beto moves to Barcelona, and meets some new women but never feels quite comfortable with them. Ironically, it is his greatest competitor who has provided him with a new job and helped him gain some sense of direction, though not a direction he has ever before considered. The novel is darkly humorous, at the same time that it deals with a talented young man with little sense of direction and no sense of purpose, a personal failure in the making. His inner thoughts, often clichéd and conventional, show little of the creativity which his landscape design suggests. It is his obvious vulnerability which draws in the reader and keeps the tension high. The conclusion, which comes as a surprise, may leave a few unanswered questions for the reader – Is the ending comic? Or is it tragic? You decide.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Rafael Lopez-Monne appears on http://www.tarragonaturisme.cat/

The Allianza Arena, the soccer/football stadium in Munich, designed by Pierre de Meuron and Jacques Herzog and built in 2006, is the first stadium in the world to have a full color changing exterior. https://www.pinterest.com/

The poster of F. W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1925) adorns the living room of Helga, the sixty-three-year-old woman who drives Beto and Marta to their hotel and later helps Beto with his travel arrangements. http://www.filmposter-archiv.de/

A post card in Helga’s living room of Edvard Munch’s Madonna, with child at the left bottom, arouses Beto’s feelings: “I felt like that monstrous infant in the corner of the painting, a fetal Baby Jesus, gazing neurotically at the ethereal beauty of his mother.” http://www.thetimes.co.uk

Beto and Helga see an exhibition of the paintings of Otto Dix, considered Degenerate Art by the Nazis. She is disgusted by it. He is not so sure. https://www.pinterest.com/

ARC: Other Press