“One huge lie that we have inherited from the rhetoric of liberty is that when it comes to the important decisions in life there’s always time to go back and make a change. But it isn’t true. Because time passes, and it’s not willing to cooperate with anyone or anything. Time has no patience for ignorance. Just like the law.”

In his second novel of what appears to be the beginning of a series, Neapolitan author Diego De Silva reintroduces hapless attorney Vincenzo Malinconico, a man lacking in ambition, commitment, and self-awareness. In his previous outing, I Hadn’t Understood, Vincenzo found himself defending a low-level criminal belonging to the Neapolitan camorra, and, much to his own surprise, being successful – the last thing he really wanted in a city in which the powerful camorra often terrorizes people who “disagree” with their way of life – and death. In the ensuing two years or so, Vincenzo has managed to stay out of the public eye, leading a conveniently quiet, though not necessarily satisfying, life. His wife, a psychologist, left him for another man more than two years ago, and he has had his own relationships, the most recent of which, with a gorgeous fellow-attorney, is currently on the rocks. Not surprisingly, given his lack of ambition, his caseload is almost non-existent: “I’m not a tough guy,” he admits. “If you want to know the truth, I doubt I’ve ever made a real decision in my whole life…I’m not a multiple-options kind of guy, really.”

In his second novel of what appears to be the beginning of a series, Neapolitan author Diego De Silva reintroduces hapless attorney Vincenzo Malinconico, a man lacking in ambition, commitment, and self-awareness. In his previous outing, I Hadn’t Understood, Vincenzo found himself defending a low-level criminal belonging to the Neapolitan camorra, and, much to his own surprise, being successful – the last thing he really wanted in a city in which the powerful camorra often terrorizes people who “disagree” with their way of life – and death. In the ensuing two years or so, Vincenzo has managed to stay out of the public eye, leading a conveniently quiet, though not necessarily satisfying, life. His wife, a psychologist, left him for another man more than two years ago, and he has had his own relationships, the most recent of which, with a gorgeous fellow-attorney, is currently on the rocks. Not surprisingly, given his lack of ambition, his caseload is almost non-existent: “I’m not a tough guy,” he admits. “If you want to know the truth, I doubt I’ve ever made a real decision in my whole life…I’m not a multiple-options kind of guy, really.”

His life changes on a simple trip to the supermarket, where the engineer friend of a former client approaches him and speaks to him, though the engineer is constantly distracted by the market’s video monitor, which shows a man “dressed like a character from The Matrix” walking around the market. After asking Vincenzo if he represents criminal cases, Engineer Romulo Sesti Orfeo suddenly warns him that something is about to happen. While Vincenzo is characteristically dithering about whether to call the police, Sesti Orfeo attacks “Matrix” with a gun, handcuffs him, then begins fiddling with the store’s video monitors, controlling the image of “the hostage” which he then broadcasts throughout the store. A fight between Matrix and the engineer leaves Matrix bloodied, his nose broken – in living color – and a crowd of shoppers gathering about, watching the action.

The two carabinieri who arrive at the supermarket remind Vincenzo of Mulder and Scully, from X-Files.

Constantly interrupting this action is a series of tiny essays on a variety of contemporary social issues, along with Vincenzo’s personal feelings about various aspects of his own life. Vincenzo is not a thinker, as the reader has already discovered, and his ironically comical observations about life are presented as if Vincenzo believes we will all rejoice in the “insights” he is presenting. Often illustrating these ideas for the reader in terms of contemporary television, films, and social media, Vincenzo speaks in simple language that reflects his decidedly unsophisticated thinking. He is especially disturbed by the fact that these thoughts keep returning with such “determination,” and he blames them for his inability to make decisions.

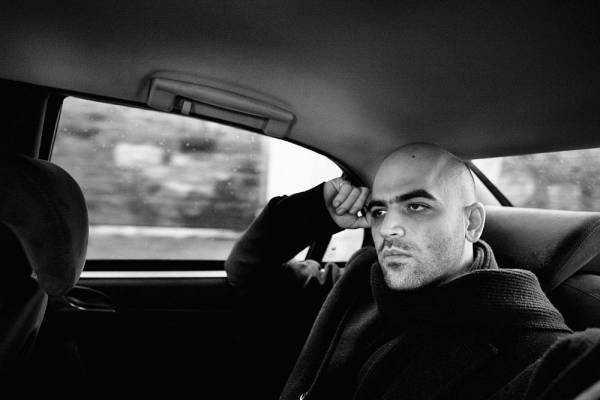

Vincenzo imagines himself as Roberto Saviano, 29, an Italian writer living under protection for having written his acclaimed book “Gomorrah.” Saviano is now on the death list of the Camorra, the Mafia group from Naples. Photo by Joao Pina

“My thoughts are a bunch of sluts, if you want to know the truth. I wish they’d stop treating me like a hotel, coming to me for consolation and help after they’ve been out doing who the hell knows what around town.” He tries to wrest control over these thoughts by writing them down, “so that I have a chance of coming up with something snappy (and more important, on topic),” but he finds, that “overtime rules forbid it. In real life I can’t delete, start over, rethink what I said, correct it. So I write.”

Amidst all the ironic moralizing, Vincenzo also reflects on his family, the most intriguing of whom is his mother-in-law Assunta, known as “Ass,” who has been recently diagnosed with cancer. She will not talk to her daughter, Vincenzo’s ex-wife, so he is the one who needs to talk to her about starting chemo. On his visit to see her and her caregiver, he brings her a bottle of Jack Daniels – hence, the title of the novel.

Vincenzo says he feels like Harrison Ford in Witness when he successfully tears down Mary Stracqualurso, an absurd TV commentator, during the standoff.

When the story returns to the hostage situation in the supermarket, the author has great fun building a satire of the media, with the Engineer talking to the camera (“he kind of looked like The Scream by Munch”), telling the employees to call the carabinieri but have them keep their distance, and waiting for the TV crew to arrive so that he can have a live trial of the Matrix character in front of the entire city. The arrival of ubiquitous TV personality Mary Stracqualurso presents Vincenzo (and the reader) with opportunities to “delight in her goatish ignorance, the way she’s chronically misinformed on any and all subjects”– in many ways similar to Vincenzo himself, just more extreme. When Mary suggests publicly that this might be a terrorist operation, Vincenzo contemplates publicly destroying her. Riffs on reality TV (including television aesthetics and contrived emotions), on TV lawyer/commentators, on newspaper quotations from prominent people regarding the situation, and ultimately on “the [inevitable] privilege of becoming a public personality,” combine with encomiums for Vincenzo on his behavior and add humor to the scenes, several of which parody TV sitcoms.

Vincenzo imagines how his life might be six months later, strolling past a cafe in Paris and seeing a girl resembling Emmanuelle Beart in Claude Chabrol’s L’Enfer

Genre-bending, like his previous novel, I Hadn’t Understood, this novel is looser in construction with many more interruptions in the flow of the narrative, if the jumping-around thoughts of Vincenzo can be considered a real narrative. His constant lecturing, while often funny, leads to obvious conclusions and few insights, other than some possible growth of Vincenzo’s personal understanding. And when the hostage standoff ends suddenly with one-third of the novel to go, it leaves the novel without the organizing framework it needs to move the novel forward, leaving it dependent on Vincenzo and his thoughts to bring it to conclusion. Vincenzo himself is neither very sympathetic nor intriguing, however, and the emphasis on the hostage situation as a metaphor for real life is something often seen on all-day news programs with all their extrapolations and second-guessing. De Silva stretches his material in many different directions, and raises many issues, conveyed through the point of view of Vincenzo, and the novel has some lively scenes with some sparkling dialogue, but I wish it had meshed more effectively – and more succinctly.

ALSO by Diego De Silva: I HADN’T UNDERSTOOD

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www2.tv2000.it/

The picture of Mulder and Scully from X-Files may be found on http://www.mtv.com/

The story of Roberto Saviano is presented here: http://www.elpuercoespin.com.ar His writing against the Camorra led to his virtual abandonment, except for his ever-present bodyguards.

Harrison Ford’s punch to a bully against the Amish in Witness may have produced the same kind of satisfaction for him as what Vincenzo felt when he verbally demolished an arrogant newswoman who invented “facts.” https://aznbadger.wordpress.com/

Emmanuelle Beart in a Parisian cafe scene in Claude Chabrol’s L’Enfer is a dream that Vincenzo contemplates for his own life near the end of the book. https://www.tumblr.com/

ARC: Europa