“The new and prodigious Joseph the Pharoah [Freud] may be; but the lean and fat kine are anything but plain old cattle! Be well assured, nonetheless, that I am eager to learn what prodigies of ennui the talking cure will dredge up from the ‘unconscious’ of your devoted friend, Henry James.”– letter from James to Edith Wharton, regarding Sigmund Freud.

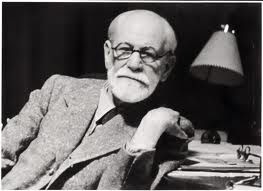

The imag ined meeting of Sigmund Freud and Henry James at James’s residence, Lamb House, is the focus of this surprising novel of ideas, which conveys the intellectual ferment in Europe just prior to World War I in a style which is filled with warmth and good humor. Henry James and Sigmund Freud seem human and even fun-loving here, but the novel is no farce. Serious issues involving James’s writing, his style, his subjects, and his repressions all come into play, even as Freud admits to having his own problems trying to reconcile James’s creativity with the “scientific knowledge” which forms the basis of his psychoanalytical principles. Freud’s questions about his research become more acute when James agrees to undergo “short term analysis” during Freud’s stay at Lamb House.

ined meeting of Sigmund Freud and Henry James at James’s residence, Lamb House, is the focus of this surprising novel of ideas, which conveys the intellectual ferment in Europe just prior to World War I in a style which is filled with warmth and good humor. Henry James and Sigmund Freud seem human and even fun-loving here, but the novel is no farce. Serious issues involving James’s writing, his style, his subjects, and his repressions all come into play, even as Freud admits to having his own problems trying to reconcile James’s creativity with the “scientific knowledge” which forms the basis of his psychoanalytical principles. Freud’s questions about his research become more acute when James agrees to undergo “short term analysis” during Freud’s stay at Lamb House.

Freud’s visit, arranged by philosopher/psychologist William James, Henry’s brother (who fears that Henry’s increasingly convoluted writing style is a sign of mental illness), is witnessed and recorded by three characters. Horace Briscoe, a friend of William James’s son Billy, is an American literature student doing his thesis on Henry James. Living at Lamb House for the summer so he can do research, he keeps a private, objectively written journal of the meetings between Freud and “Uncle

Edwin M. Yoder

Henry,” as James has asked to be called. At the same time Henry James is writing almost daily letters to a friend, author Edith Wharton, describing his often amused reactions to Freud’s attempts to discern his “secrets of the alcove,” along with his creation of apocryphal stories for Freud. Freud, in turn, is keeping his own notes on James, which he plans to use for his research.

Each of the “biographers” has personal goals. Horace is excited to be a witness to history, but he is also wildly in love with Agnes Fengallon, the daughter of a conservative preacher, and he and Agnes want to spend as much time as possible discovering the secrets of their own alcoves. Henry James regards his meeting with Freud as an intellectual contest, and he invents memories for Freud while refusing to give up information regarding his sexual history or identity. Freud is attempting to reconcile his own interest in art, as seen in his writings about Michelangelo and Leonardo, with the “scientific” basis of psychoanalysis, which, he believes, may not explain the imagination or creativity. His questions to James about his novels reflect the Freudian interpretations of these books.

Henry James

The body of the novel, set in 1908, alternates with sections written by Horace Briscoe in 1941, by which time James has been dead for twenty-five years, and Briscoe is now a middle-aged professor at Johns Hopkins. Freud has been dead for two years, and his colleagues and heirs, feeling Freud’s legacy threatened by the beliefs of Jung and Adler, have become “keepers of the flame,” insisting on doctrinaire psychoanalytical interpretations of Freud’s writing. Briscoe has borrowed Freud’s notes of his 1908 “analysis” of James from the Freud archive, and he fears that these notes will be burned by Freud’s disciples if they show Freud having any doubts about psychoanalysis. He is determined to protect these notes as historical records.

Sigmund Freud

Beautifully constructed to highlight the issues of the day, the novel is also great fun to read. Yoder manages to humanize James, an author who remains personally remote for most readers, however much they may admire his work. Here James is mischievous, a man who delights in trying to outfox Freud. Telling Freud of his relationship with long-time friend Constance Fenimore Woolson, a woman who died after falling or jumping from a window in Venice, for example, James relates the story of how, after her death, he took her clothing out to sea and threw it into the lagoon, an account that he privately admits is fictional. He refuses to be drawn into discussions of The Turn of the Screw or elaborate on Isabel Archer’s bad marriage in Portrait of a Lady.

Constance Fenimore Woolson

Written in a lively style which never becomes ponderous, even when discussing heady literary and philosophical issues, the novel is a delight to read. While it certainly increases the reader’s pleasure to have a good working knowledge of James’s novels, Yoder writes so clearly that readers less familiar with James will find much to enjoy and even more to admire in this novel. Beautifully paced, with serious themes and intellectual discussions alternating with playful scenes, the novel captures the intellectual face-off of two “lions” who enjoy meeting each other as much as the reader enjoys imagining their meeting. Though Henry James expected “the talking cure” to dredge up “prodigies of ennui” from his unconscious, he greatly underestimated the prodigious talents of his “biographers,” Horace Briscoe, Sigmund Freud, and, especially, Edwin Yoder. (My Favorite novel for 2007)

Credits: The author’s photo appears on http://journalism.wlu.edu

The photo of Henry James is from http://danassays.wordpress.com

The photo of Sigmund Freud is from http://blog.syracuse.com

The photo of Constance Fenimore Woolson appears on http://elizabethfoxwell.blogspot.com