“The eight boys, [Blood Brothers], have spent the whole endless winter’s night on the street. As so many times before: homeless. Always trudging on, always on the go. No chance of any shut-eye in this weather. Day-old remnants of snow, the occasional thin shower of sleet, everything nicely shaken up by a wind that makes the boys’ teeth chatter with cold. Eight boys, aged sixteen to nineteen…on their own.”

At last, a novel recently discovered in Germany and written in 1932, at the end of the Weimar Republic, presents a picture of Berlin as it really was, not as it appears in the sterilized portraits released by Hitler’s army and staff beginning a year later, when Hitler officially came to power. Like many other cities recovering from a Depression, Berlin did have its seamy underside, along with the poor, the homeless, the street gangs, and the petty criminals dependent on pickpocketing and small thefts in order to eat. Poor women, of course, had their own resources, with prostitution and the bar scene playing a big role in their lives. Whole sections of the city were occupied at night by the wandering homeless, including young teens. The best that many of them could hope for, as they looked for a place to keep warm, seemed to be the temporary hostels, filled with smoke and the stench of unwashed bodies, where they could stay, and perhaps get some sleep, during brutally cold days.

At last, a novel recently discovered in Germany and written in 1932, at the end of the Weimar Republic, presents a picture of Berlin as it really was, not as it appears in the sterilized portraits released by Hitler’s army and staff beginning a year later, when Hitler officially came to power. Like many other cities recovering from a Depression, Berlin did have its seamy underside, along with the poor, the homeless, the street gangs, and the petty criminals dependent on pickpocketing and small thefts in order to eat. Poor women, of course, had their own resources, with prostitution and the bar scene playing a big role in their lives. Whole sections of the city were occupied at night by the wandering homeless, including young teens. The best that many of them could hope for, as they looked for a place to keep warm, seemed to be the temporary hostels, filled with smoke and the stench of unwashed bodies, where they could stay, and perhaps get some sleep, during brutally cold days.

Contributing books for a book burning: From the German Federal Archives: bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B0527-0001-776.

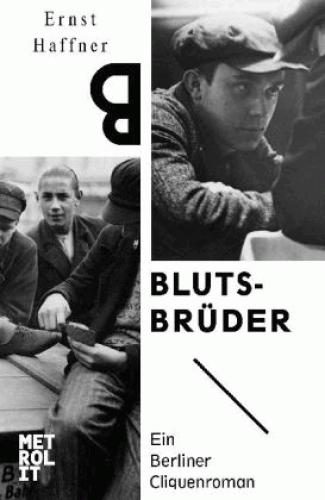

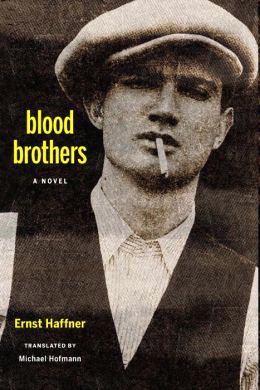

Ernst Haffner, the journalist who wrote this novel, uses a collection of individualized vignettes, connected by the overriding story of two of the young men, Ludwig and Willi, to show Berlin as it really was. Little is known about Haffner. The city registry shows that he was a resident in Berlin between 1925 and 1933,* and some speculate that Haffner, because of his insights into the nature of the lives of the homeless, especially the young homeless, might have been a social worker. At the time of the book’s publication in 1932, it attracted considerable notice in Germany for its honesty and its insights, and it was well reviewed in German newspapers, but it was outlawed by Hitler the following year, and virtually every copy was burned in the Nazi book-burnings. Haffner, according to the records, was summoned by the culture ministry of the Third Reich in 1938, after which he disappeared, with no record of his residence anywhere in Germany after that. Not a single photograph of Haffner remains.* Somehow at least one copy of the book survived, however, and in 2013, it was republished in Germany and released at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Now translated into English by the esteemed translator Michael Hofmann and published by Other Press, it fills out the picture of life in Berlin by incorporating the lives on its fringes – its poor, its jobless, its gangs, and its homeless.

The novel opens on a cold winter day as eight boys, who consider themselves “Blood Brothers,” are waiting at a welfare office where it is warm. They have been up all night, out in the cold, and as the number of people waiting there is large, they can sleep relatively undisturbed without being noticed. When twenty-one-year-old Jonny, one of the “brothers,” arrives with cigarettes, the group, awakened, knows that he has money and that they will get food that day. Leaving in groups of three so that they do not attract attention from the authorities, they go out to find breakfast at a bar that is as close as they can get to “home.” There they can get broth, liver sausage, rolls, and potato pancakes, and then smoke and snooze some more. Another bar serves for the evening meal. On this particular night, Jonny has arranged for them to spend the night in a dark warehouse, as long as they are out before the work crew arrives the next morning. The author’s descriptions are depressingly specific – the crates, the straw they sleep on, a boy’s jacket used as a pillow, the mice, and the uncertainty each feels as no one knows what tomorrow will bring. Their interdependence is their only way of surviving.

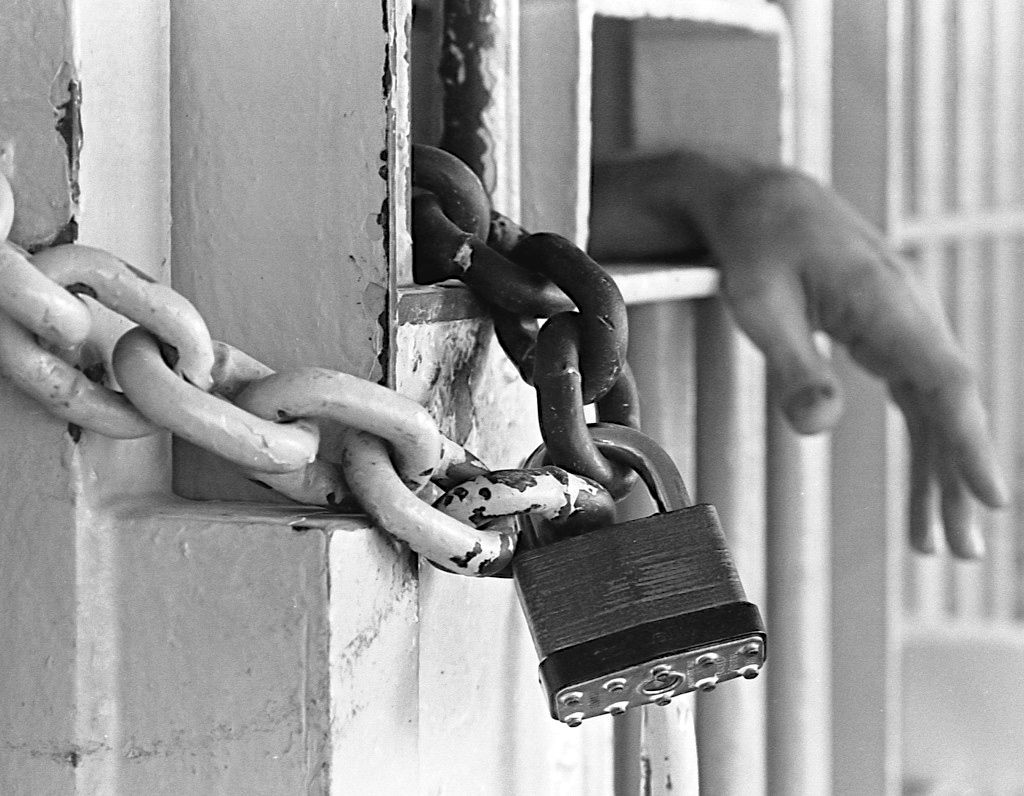

Gradually, the reader comes to know some of the characters individually, especially Ludwig and Willi, who become the main characters, their stories alternating with those of the majority of the gang. Willi has escaped from “the institution,” and the unsophisticated Ludwig has fallen for an old scam and ends up in jail, gulled by an older man. The description of how Willi rides the rails to Berlin by hanging on the axle under a train car carries the ring of truth, and shows how the young and naïve learn from older, more expert homeless youth who share their knowledge. Ludwig, on remand in prison for something that was the result of his gullibility, receives a package of treats from the gang, something that makes his predicament more bearable.

In a scene that illustrates the conflicts these young people have, Ludwig is transported to serve his short prison term by a kind man who treats him as a human being, someone who is not interested in publicly humiliating him. Ludwig is grateful, but when he gets the chance to escape, he is so desperate he cannot resist hurting the only official who has ever been kind to him. When he later runs into Jonny by accident, his pleasure at returning to the gang and his appreciation of the gifts they have for him are immeasurable. Later, his accidental meeting with Willi affects his future life. They both feel that the gang is changing and becoming more preoccupied with the unearned fruits of their labors as pickpockets of the poor and as petty criminals, and Ludwig and Willi decide to look for a new direction. Their way is not smooth, and many difficulties arise as the novel continues. Both make mistakes.

The fates of other individualized characters from the gang show the fickle nature of fate and the difficulties which groups acting as gangs can create from within: The influence of peer pressure and group action leads to a loss of individuality and the loss of a sense of responsibility for the actions of the group. The importance of having the right papers and the limitations placed on those who do not have them are also problems for the boys. Ultimately, Haffner creates a full picture of about dozen young people and the lives that they have chosen or had thrust upon them as a result of their poverty and lack of opportunity. His depiction of this sector of Berlin’s lower life is real, clear, and uncompromising, far different from all the Nazi photos of clean-cut, well-pressed blonde youth celebrating the arrival of Hitler. An important and realistic book that adds to the true picture of life in Germany in the early 1930s.

Book-burning, 1933: from the German Federal Archives: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14597 / CC-BY-SA, from May 11, 1933

Photos, in order: Collecting books for a book burning: From the German Federal Archives: bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B0527-0001-776. http://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de

Cold, homeless boy, much like the boys in this novel, a photo that wrings the heart: http://www.travel-studies.com Photo from 1935.

Racing for the train: http://www.travel-studies.com/

Hands in jail: http://akarpinski.hubpages.com Source: http://www.eji.org/

Book-burning: from the German Federal Archives: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14597 / CC-BY-SA, from May 11, 1933. http://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/

ARC: Other Press