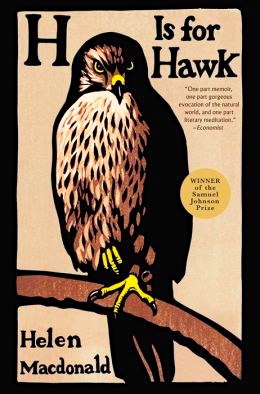

Note: This book was WINNER of the Costa Award for Biography in 2014, and was also WINNER of the Samuel Johnson Prize, the UK’s most prestigious non-fiction award.

“Walking in a foggy ride at dawn, you turn your head and catch a split-second glimpse of a bird hurtling past and away, huge taloned feet held loosely clenched, eyes set on a distant target. A split second that stamps the image indelibly on your brain and leaves you hungry for more. Looking for goshawks is like looking for grace: it comes, but not often, and you don’t get to say when or how.”

Devastated by the sudden death of her father when she is in her early thirties, author Helen Macdonald finds herself lost, overwhelmed, and dealing with a “kind of madness.” She and her father were especially close. They had loved walking for hours in the woods of Hampshire, where she had always loved seeing the falcons and hawks. Her parents, sympathetic, had even allowed her, after much pleading, to accompany a group of falconers, hunting with goshawks in the field, when she was only twelve. As her parents drove off, however, she was suddenly terrified, “Not of the hawks: of the falconers. I’d never met men like these. They wore tweed and offered me snuff.” She “pushed her fears aside in favor of silence, because it was the first time [she]’d ever seen falconry in the field.” Within the first twenty minutes, she sees an enormous goshawk kill a pheasant, an event which draws her to the site of the kill, where she picks six coppery feathers free, holding them in her fist “as if I were holding a moment tight inside itself. It was death I had seen. I wasn’t sure what it had made me feel.”

Devastated by the sudden death of her father when she is in her early thirties, author Helen Macdonald finds herself lost, overwhelmed, and dealing with a “kind of madness.” She and her father were especially close. They had loved walking for hours in the woods of Hampshire, where she had always loved seeing the falcons and hawks. Her parents, sympathetic, had even allowed her, after much pleading, to accompany a group of falconers, hunting with goshawks in the field, when she was only twelve. As her parents drove off, however, she was suddenly terrified, “Not of the hawks: of the falconers. I’d never met men like these. They wore tweed and offered me snuff.” She “pushed her fears aside in favor of silence, because it was the first time [she]’d ever seen falconry in the field.” Within the first twenty minutes, she sees an enormous goshawk kill a pheasant, an event which draws her to the site of the kill, where she picks six coppery feathers free, holding them in her fist “as if I were holding a moment tight inside itself. It was death I had seen. I wasn’t sure what it had made me feel.”

Now, much older, she understands. Following her father’s death, she says, “I felt odd: overtired, overwrought, unpleasantly like my brain had been removed and my skull stuffed with something like microwaved aluminum foil, dinted, charred, and shorting with sparks.” Her instinctive reaction is to go to “the broken forest” to see the goshawks, “things of death and difficulty: spooky, pale-eyed psychopaths that lived and killed in woodland thickets.” Though Macdonald had eventually owned and trained smaller falcons, and had once worked at a bird-of-prey center on the border of England and Wales, she had never before been interested in owning or training a goshawk. Now, in the summer after her father’s death, however, she begins to think that owning one is inevitable. The secret to a well-behaved goshawk, she has read, was to “give it the opportunity to kill. Kill as much as possible… murder sorts them out.” Angry and upset and at loose ends, she feels a kind of kinship with the goshawk as a species, and since she has “no partner, no children, no home and no nine-to-five job,” she decides to use the summer to train the ultimate hawk, the wild goshawk, a job which will make her face her fears and her talents in new ways.

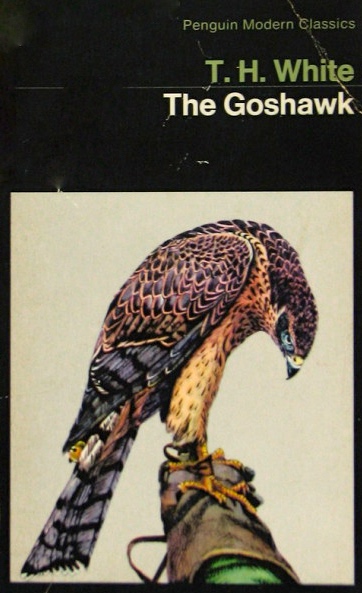

Ignoring the advice of an old friend, who told her “Don’t do it. It’ll drive you mad,” Macdonald acquires Mabel, a young goshawk from Northern Ireland, then sets out to train her, the goal being to let her eventually fly free to hunt, then return to Macdonald’s gloved hand. Her guide in this task is author T. H. White, who, in addition to writing The Sword in the Stone and The Once and Future King, also wrote The Goshawk, a book about his own attempts to train a goshawk in the early 1930s. Macdonald tells the story of White in parallel with her own. Both authors were suffering from emotional problems when they were working with goshawks, but both were devoted to the task, a huge undertaking involving near seclusion with a fierce and independent animal requiring full-time attention. Training the goshawk takes on symbolic meaning for both authors, with success never guaranteed. In alternating narratives of her own discoveries and those of White, Macdonald describes the taming and training – the “manning” of the hawk – eventually going in her own direction in the belief that White made some serious errors with Gos, his hawk.

In the vocabulary of the “austringer,” a person who trains hawks, Macdonald explains the equipment she uses – jesses, anklets, creances, hoods, and bells for the hawk – and each milestone is a cause for celebration, not just for the author but for the reader. Comparisons in the waiting time for the hawk to obey are made with the waiting times for the perfect photograph, which Macdonald says her father endured as a professional photographer. Psychological transference and projection between trainer and goshawk become big issues, and for much of the book Macdonald is unsure whether she is the trainer or the one being trained. She says that “there was nothing that was such a salve to my grieving heart as the hawk returning [to hand]” and admits that “I felt incomplete unless the hawk was sitting on my hand.” Her identification with Mabel during training becomes almost total. “Out with the hawk, I didn’t need a home. Out there I forgot I was human at all.”

Hunting with Mabel, however, teaches Macdonald some important lessons, climactic moments here. “Hunting…took me to the very edge of being human…yet every time the hawk caught an animal, it pulled me back from being an animal into being a human again.” Mortality and death, constant presences in hunting, create, for Macdonald, a sadness for the mortality of the animals killed by Mabel. Eventually, she learns that “The wild is not a panacea for the human soul; too much in the air can corrode it to nothing.”

During her eulogy at the memorial service for her father, in late summer, she finally realizes that the two hundred people who listen to her share her feelings – that she is not as alone as she has felt – and she concludes that “falconry is a balancing act between wild and tame, not just in the hawk, but inside the heart and mind of the falconer.”

In this brilliantly described and vivid depiction of the meaning of life and death, Macdonald connects with readers in unique ways, and it’s hard to imagine anyone who will not be changed by this incredibly moving work: “In my time with Mabel, I’ve learned how you feel more human once you have known…what it is like to be not. And I have learned, too, the danger that comes in mistaking the wildness we give a thing for the wildness that animates it.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.independent.co.uk/

Mabel, a photo by the author, is shown on http://www.theguardian.com/

This edition of the T. H.White book of The Goshawk was found on https://stancarey.wordpress.com/

The goshawk capturing prey over water is from http://www.desk7.net

The goshawk with jesses on its legs appears on http://www.crownfalconry.co.uk