Note: Eugen Ruge was WINNER of the German Book Prize for his previous novel, In Times of Fading Light.

“I remember my surprise at suddenly finding myself in my kitchen, in exactly the same attitude…that I had carried out in just the same way the morning before (and the morning before the morning before), and for a moment I had the feeling that it was the same morning and I was the same man, a man who like the undead, was doomed to repeat the same sequence again and again.”–Peter Handke, narrator of this novel.

Author Eugen Ruge grew up in East Berlin during the time of the Berlin Wall and lived there, working as an academic, till the age of thirty-four, leaving the East for the West a year before the Wall fell, and perhaps it is this background which has inspired him to create a main character like Peter Handke. Handke, also a man from Berlin, has lost his sense of direction, and he has decided to start over in a new country. Not as young as he seems, he is a former professor of chemical engineering with a well-paid, permanent position, one he has recently resigned in order to become a writer. He has had only minimal success since then. Handke is disconnected from those around him, a profound loss of motivation preventing him from making needed changes in his world. In another environment, he believes, he will be able to write the novel he has always dreamed of. Though his father, also a writer, considers his own work in history and philosophy to be far more important than Peter’s work (mostly light satire, to date), he nevertheless gives him some funds to help him get started in a new country. The attitude he conveys, however, leads Peter to confess that “I seemed to myself rather dull-witted,” not a happy thought for someone planning to create a new life.

Author Eugen Ruge grew up in East Berlin during the time of the Berlin Wall and lived there, working as an academic, till the age of thirty-four, leaving the East for the West a year before the Wall fell, and perhaps it is this background which has inspired him to create a main character like Peter Handke. Handke, also a man from Berlin, has lost his sense of direction, and he has decided to start over in a new country. Not as young as he seems, he is a former professor of chemical engineering with a well-paid, permanent position, one he has recently resigned in order to become a writer. He has had only minimal success since then. Handke is disconnected from those around him, a profound loss of motivation preventing him from making needed changes in his world. In another environment, he believes, he will be able to write the novel he has always dreamed of. Though his father, also a writer, considers his own work in history and philosophy to be far more important than Peter’s work (mostly light satire, to date), he nevertheless gives him some funds to help him get started in a new country. The attitude he conveys, however, leads Peter to confess that “I seemed to myself rather dull-witted,” not a happy thought for someone planning to create a new life.

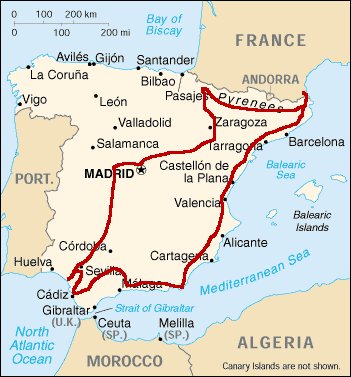

A novel of absurdity which sometimes borders on the bizarre, Cabo de Gata (“Cape of the Cat”) begins with Peter’s travels from Basel to Barcelona and then on to Andalusia, the southernmost region of Spain. There he meanders long the southeast coast toward Cabo de Gata, about a hundred fifty miles due east of Malaga. His arrival there does not reflect the romantic promise that Peter expects of a place described as “a breath of Africa,” just across the Mediterranean. He “remembers the wretched (pink) buildings,” finding it hard to say “whether they are still being built or already falling into ruins,” along with mended tarmac, broken paving stones, and rocks piled up, and he feels that “the whole landscape looks like a sparsely overgrown dump.” Wind blows sand into his eyes, yapping dogs surround him as he walks, and the church and a row of tiny, two-story houses show no signs of life. He is stunned, reflecting like a film director that “if I seem to myself in those long minutes like a character from a film, it may be because I keep my hat on throughout this entire scene.”

The author’s close attention to detail enables the reader to see the world through Peter Handke’s eyes as he first decides to leave Cabo de Gata, and then later decides to stay. At one point during a walk along the “beach,” he finds a spiral conch shell and decides to take it home, only to discover that inside the shell a pair of “black button eyes” belonging to a hermit crab look out, though the crab itself is dead. Since Peter’s sign of the zodiac is Cancer the Crab, he thinks this may be an omen that he should stay, and fascinated by a group of small birds which he thinks of as “hysterical aunties,” he eventually lets loose with a loud shout. “I think it was simply a cry of rage, not of triumph, not a liberating roar, but a short sound of blatant annoyance that an outsider might have taken as my reaction of an insect bite.”

Eventually renting a small room for three months, managed by the grumpy old woman who runs the only café, Peter Handke begins his new life. Not having a desk in his tiny room, he writes sitting on a bench outside, and when he wants to take a break to read, he lies in bed with the only book he has brought with him, Henry Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi. Gradually, he comes to feel comfortable in his walks along the promenade and begins to have a “strong sense of belonging to all this,” his change of attitude leading him to tear out a first sentence he’s written in his notebook in favor of a newer, more positive opening. He discovers a shallow lake filled with flamingos, “and it seems to me entirely absurd, positively deranged, to doubt the existence of God.” The arrival of an Englishman who leaves after two days, and later an American who vanishes in a storm leave Peter alone again, and he decides to pay more attention to the people who live there while contemplating life’s biggest questions and analyzing his dreams. Can the world really be perceived? Is the world on television the real world and the world he lives in an illusion, or the other way around? Eventually, a feral cat appears in his life, and changes his approach to the world as he tries to tame her. As she stalks like a lion, he is reminded that his deceased mother was a Leo, and he begins to draw some bizarre conclusions about external forces.

The novel ends without a clear resolution, adding to the feeling that this novel defies all the “rules” and presents itself on its own terms. Peter Handke is not a “hero” or even an anti-hero. He is too neutral and uncommunicative to attract the long-term interest of the reader, and his journey is a solitary one, with no antagonist, other than life itself, to fight him. He raises questions but does not come to many conclusions, and those he does draw are often offbeat and darkly comic. There is some satire in Peter’s search for philosophical answers (perhaps a rebellion against his father the philosopher), and the novel is clever and written with exquisitely descriptive prose (beautifully translated by Anthea Bell). The “Seven Puzzles of Cabo de Gato,” written as if they were the seven biggest mysteries of the world – Peter’s world – are one of the novel’s highlights, with the author obviously having fun, and the use of a feral cat as a possible deus ex machina is clever and fun to read. Readers who can be satisfied with letting the novel unfold on its own terms will enjoy this unusual and often humorous creation which offers more than mere laughs.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.plotpoint.ch/

Fishing boat on the rough coast and beach of Cabe de Gata. http://www.juntadeandalucia.es

The flamingos of Cabo de Gata attract many visitors each year to southeast Spain. http://www.juntadeandalucia.es

Cabo de Gata is about 150 miles due east of Malaga, on the coast. This red line represents the itinerary of a bird-watching program. Click to enlarge. http://www.avg-w.com/

ARC: Graywolf Press