“It is the eyes that make the picture great. The soldier’s eyes look out directly from the page. They look out and through – or perhaps they are not looking at all but seeing only what they have seen already, images that are imprinted on the retina and on the memory so strongly that they cannot be supplanted by whatever is before them now. This soldier has seen horrors first hand. Perhaps he has been a perpetrator….” – speaker Jonathan Ashe, photographer, in Vietnam.

Like so many other young men in the 1960s, Jonathan Ashe, a young man from a farm in rural Norfolk, England, has escaped his small village to travel the world and, on some level, to find out who he really is. He and his older brother, who has been left in charge of the family farm following the death of his father, have little in common, and some event from the past has alienated them. Though he has feelings for his mother, he cannot bring himself to write to her on a regular basis. Now in Viet Nam, half a world away from England, Jonathan decides to challenge himself as a photographer during the Vietnam War, anxious to expand his views of the world in an effort to understand more about life and death and survival. Jonathan’s own father died of an accidental gunshot wound when Jonathan was a young child, and the suddenness of the death and the memories he has of the aftermath have haunted Jonathan ever since. Now he as he thinks back on his childhood, he wonders how much of what we remember about a person or event is actually real and how much is what we wish for – or what we choose to remember? Can we ever learn to see traumatic experiences in new ways without lying to ourselves and others about the realities?

Like so many other young men in the 1960s, Jonathan Ashe, a young man from a farm in rural Norfolk, England, has escaped his small village to travel the world and, on some level, to find out who he really is. He and his older brother, who has been left in charge of the family farm following the death of his father, have little in common, and some event from the past has alienated them. Though he has feelings for his mother, he cannot bring himself to write to her on a regular basis. Now in Viet Nam, half a world away from England, Jonathan decides to challenge himself as a photographer during the Vietnam War, anxious to expand his views of the world in an effort to understand more about life and death and survival. Jonathan’s own father died of an accidental gunshot wound when Jonathan was a young child, and the suddenness of the death and the memories he has of the aftermath have haunted Jonathan ever since. Now he as he thinks back on his childhood, he wonders how much of what we remember about a person or event is actually real and how much is what we wish for – or what we choose to remember? Can we ever learn to see traumatic experiences in new ways without lying to ourselves and others about the realities?

Jonathan hopes that viewing the world through the uncompromising lens of a camera will provide him with some new understandings. In Vietnam he accepts a ride in a helicopter from a young pilot who is about to fly over a battle site, thereby setting in motion his personal quest to observe, digest, and live with some of life’s most difficult truths. In clear language and a style which is so simple in its structure that it sometimes resembles poetry, British author Georgina Harding follows Jonathan as he sees a reality more horrific than he has ever imagined. Arriving at the scene of a battle in the copter piloted by his new friend, Jonathan is at first disappointed that the battle is essentially over, but as they are looking for a place to land, he sees a young woman, screaming and clutching her belly, severely wounded. Out of the corner of his eye, he thinks he sees an American soldier running toward her and firing at her head, but he cannot be sure. A few minutes later, when the chopper lands, Jonathan gets out and hurries toward the smoke, “and then he [sees] the soldier…very still…seated on the ground with his back to a wall, his knees bent up in front of him and his two hands clamped to the barrel of the gun held upright between them…Beyond the soldier, the village. The houses were burning.”

Taking a quick picture of the soldier, who is unmoving and silent, he moves on to see dead bodies crumpled on the ground, seemingly stopped in mid-action, dead children and pets with legs all entangled, and numerous bodies floating in the river, obviously shot from above. Soon he finds the body of the wounded woman he had previously seen from the air – a young woman, the mother of a baby. She has a new wound in the center of her forehead. He takes a picture of her, and moves on. On the way back to the chopper, he once again sees the soldier by the wall – he has not moved an inch in the forty-five minutes that have passed, and continues to stare straight ahead, completely oblivious to all that is happening. Jonathan takes a second picture of this stunned soldier, then returns to base, packs everything he owns, and hastens back to Saigon, well out of the field of battle. While there, he learns from the radio that an atrocity has occurred in the village that he has just photographed. He responds to the news, and his photos of this village – and especially his iconic photo of the stunned soldier – soon appear all over the world.

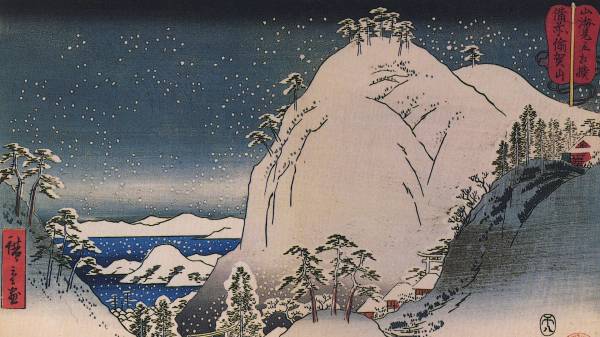

This beginning contains the seed of every other event which follows in the novel. No further warfare and no more bloodshed occur, but Harding’s purposes – to show the more personal and long-lasting effects of trauma and the more universal aspects of responsibility and humanity – develop with insight and deep feeling, as Jonathan Ashe, his last name appropriate to his role in the novel, moves on to Japan and a new life. Teaching English to Japanese students, “Jonathan tries to become part of society there, taking pictures wherever he goes, but even he sees that “All that is in his pictures when he first comes to Japan seems material, except the sky.” He is surprised by how cold Japan can be in February, though he has long been familiar with the Hiroshige prints of snow falling. He takes long walks, believing that “the less he held to himself, the more he gave to the crowd, the more he would be part of the place, understanding it in its present.” He finds a favorite bar, which he enjoys at night, but he does not really connect with others until he meets Kumiko. The story of their relationship, which depends on her patience and insight, rather than any genuine commitment on his part, provides much of the drama and pleasure of the novel.

Jonathan is intrigued by the fact he can buy a bottle of whiskey in a bar in Japan, and they will put his name on it and use it for him alone when he orders whiskey. Note individual names on bottles in Japanese.

Several overlapping events connect the various parts of the novel. Jonathan Ashe’s father had been a soldier in World War II and had fought in India, Assam, and Burma, where he had fought the Japanese in the jungle and never really recovered. Kumiko’s grandfather now senile, fought the British in Burma, and was so traumatized that even now he insists that his garden always be tidy and neatly trimmed so that it does not resemble the jungle in which he fought. As Jonathan notes,

“War is the most concrete thing. The memory of war will stay with a man longer than anything else he will ever know.”

British Jonathan and Japanese Kumiko must work their way through much family history, culture, and Jonathan’s own trauma in order to reach a meaningful understanding, and when Jonathan, walking down the street, suddenly sees the soldier he once photographed in Vietnam during the shooting of the young woman, he follows him, eventually meeting and coming to know him and his girlfriend and gaining some new insights about himself. Harding keeps her style simple and quiet, and except for one unlikely coincidence, the novel resonates with honesty and truth, as Jonathan begins to find out what he needs to do to feel happy, ending the novel on an upbeat note.

ALSO by Georgina Harding: THE PAINTER OF SILENCE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.vertigolibri.it/

The war photo from the Vietnam War, “War is Hell,” is from http://www.businessinsider.com/

“Snowfall” by Adro Hiroshige may be found here: http://www.dominicanajournal.org

Bottle storage at some bars in Japan, where people buy bottles for their exclusive use, over time, each carrying his/her own name is described on http://www.japan-talk.com/jt/

Shinjuku Gyoen, a public garden in Shinjuku, is a place where Jonathan enjoyed walking with Kumiko: http://www.urbancapture.com/

ARC: Bloomsbury