“[My daughter] cannot conceive that we are really living in the end of times, that it’s goodbye to…all the goodies we had in the past. The easy days will not come again; they were a one-off, an abortive mutation in the evolution of civilization, as the peacock’s tail is over the top when it comes to attracting the dowdy peahen, merely an over-response.”

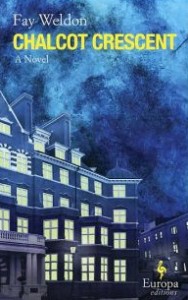

Fay Weldon, the immensely popular British author of twenty-nine previous novels, creates an unusual variation of metafiction in this largely satiric novel from 2010, about Britain’s twenty-first century issues as she sees them. Here, an elderly author is sitting on the stairs behind the closed front door of her house in Chalcot Crescent, evading the bailiffs who want to talk with her about her debts. The beleaguered author is Frances Prideaux, whose life parallels that of Fay Weldon in almost every key issue. Frances, however, says she is the sister of Fay, an author she claims is now reduced to writing cookbooks. Frances herself has written dozens of successful novels before losing her audience and spending more money than her novels are earning, and she has now decided to write “a fantasy about alternative universes…There are an infinite number of universes, too many to contemplate.”

Fay Weldon, the immensely popular British author of twenty-nine previous novels, creates an unusual variation of metafiction in this largely satiric novel from 2010, about Britain’s twenty-first century issues as she sees them. Here, an elderly author is sitting on the stairs behind the closed front door of her house in Chalcot Crescent, evading the bailiffs who want to talk with her about her debts. The beleaguered author is Frances Prideaux, whose life parallels that of Fay Weldon in almost every key issue. Frances, however, says she is the sister of Fay, an author she claims is now reduced to writing cookbooks. Frances herself has written dozens of successful novels before losing her audience and spending more money than her novels are earning, and she has now decided to write “a fantasy about alternative universes…There are an infinite number of universes, too many to contemplate.”

The alternative universe of the novel Frances is writing in 2010 exists in the not-so-distant future of 2013, a time in which Frances sees Britain in even more dire straits financially and socially. Her novel-in progress, a broad satire of the issues she sees dominating British life in the immediate future, alternates her political commentary with observations on her own life and that of her family and how they are affected by the changes. The “Shock of 2008” has been succeeded by the “Crunch of 2009 – 2011,” including the “Squeeze and Inflation,” which leads to the phony “Recovery of 2012” and finally the “Bite of 2013.” It is a time of fuel allowances, ration books, wages given in Euros (often late), roads and other infrastructure in decay, power cuts, water shortages, mandatory sharing of cars, sixty percent unemployment, no arts or funding for them, and banks which charge the depositor for putting the money into the bank.

The National Unity Government (NUG) controls all, the National Institute for Food Excellence (NICE) feeds the people (mostly on National Meat Loaf, made from suspicious substances), and housing is provided by the National Institute of Homes for Everyone (NIHE). Neighborhood Watch, aided by CiviCams, keep an eye on all local activities and “protect the peace.” Greenpeace has become the much more radical Redpeace (“almost a cult”), all charities are merged into the nationalized CiviGaia, roving gangs control the streets, and people are awaiting the New Republic to come.

As Frances declares that she must “somehow find my inner bitch,” the reader learns about her child out of wedlock, her many marriages, the out-of-wedlock child of her oldest daughter, the marriages of her two daughters, all the children from their marriages and liaisons, and their relationships with her and with each other, a maze of characters as complex as the social issues she has been discussing. Several of the grandchildren and their friends have suddenly appeared at Frances’s house in Chalcot Crescent, intent upon using her house as the central headquarters from which they plan to capture an important person in the government and hold him in the empty house beside her while conducting their own coup.

Weldon’s social and political commentary are to the point and have much potential, but that, and the satire associated with it, are heavy-handed, lacking the light humor and subtlety that allows the reader to participate in the fun. Frances herself recognizes this, noting that her writing has changed from her style of the past: “I write less implicitly [now], more explicitly, if you understand the distinction, but not so well,” certainly a facetious remark, though it does give the reader pause. Annoying aphorisms pop up everywhere to explain what is obviously going on, and revealing Frances’s closed mindset: “Money gives you confidence,” “You can laugh at authority,” “Fate determines all things. What happens was meant to be,” and “Possessions are for the middle-aged, not for the old.” And though Frances introduces numerous characters from her life and describes what happens to them, their importance to the thematic unity of the novel is unclear. Much information is repeated unnecessarily, and the novel, overall, feels rough and fragmented, “scattered” and less focused than what one expects from a novelist of Weldon’s stature.

ALSO by Fay Weldon: KEHUA! BEFORE THE WAR

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appear on http://whyjaneausten.com/writers.html

The photo of Chalcot Crescent, by Simon Richardson, is from http://commons.wikimedia.org

ARC: Europa