“There is a degree to which novels will write themselves if you allow them to, but the process of allowing them to do so is tiring, difficult, and registers with the writer as really hard work…It’s like taking a strange dog for a walk on the end of a lead: it either charges ahead in the wrong direction, or has to be tugged behind, or turns and snaps at your ankles, or worse, just sits down on its haunches and stares at you.”—Author Fay Weldon

Metafictional novels, in which the author becomes one of the main characters, are very tricky. Though they pretend to be spontaneous, with the author commenting on the actions she and her characters are performing on two or more different narrative planes, they are also patently artificial, with the author carefully preparing, editing, and sometimes rewriting these “spontaneous” comments about the nature of her work. Some authors, in their self-conscious commentary, try too hard to make the reader understand what it takes to be a writer and end up sounding either patronizing or “cute.” Others forget that most readers are looking for an exciting story with lively and intriguing characters and instead get bogged down in their own stories, instead of the stories of their characters.

Metafictional novels, in which the author becomes one of the main characters, are very tricky. Though they pretend to be spontaneous, with the author commenting on the actions she and her characters are performing on two or more different narrative planes, they are also patently artificial, with the author carefully preparing, editing, and sometimes rewriting these “spontaneous” comments about the nature of her work. Some authors, in their self-conscious commentary, try too hard to make the reader understand what it takes to be a writer and end up sounding either patronizing or “cute.” Others forget that most readers are looking for an exciting story with lively and intriguing characters and instead get bogged down in their own stories, instead of the stories of their characters.

Fay Weldon, author of thirty-four novels by 2010, when this book was written, strikes a fine balance as she alternates between narrative, perfect dialogue, and metafictional commentary, most of it very funny, and the reader cannot help but become involved on many levels. She makes her writing life sound so intriguing that I found myself playing along, imagining myself as the creator of the dysfunctional characters in “this tale of murder, adultery, incest, ghosts, redemption, and remorse.” Like the dog in the opening quotation, some of these characters do charge ahead in the wrong direction, some do need to be pulled along from behind, a few turn and snap at you, and some do just sit down and stare – at least for short periods of time – and it is this very tension between Weldon and her characters which makes this novel such an unusual treasure.

The Coromandel Peninsula juts from the east coast of the North Island, between Auckland and Tauranga. Double click to enlarge.

Weldon focuses not just on four generations of one family, from seventy-seven-year-old Beverley, three times a widow but not averse to marrying again, to her estranged daughter Alice, her adult grand-daughters Cynara and Scarlett, and her teenage great-granddaughter Lola, along with all their many lovers and husbands. She also focuses on the invisible spirits which have come with Beverley to England from New Zealand, where she grew up (as did the author). These kehua are the Maori spirits of the wandering dead, “adrift from their ancestral home,” charged with “herding stray members of the whanau (extended family) back home so the living and dead can be back together in their spiritual habitation.” They are particularly concerned, in this case, with something that happened to Beverley when she was three years old. Walter, her father, killed Kitchie, her mother, in New Zealand, leaving Beverley an orphan. Since their bodies never received a proper burial in the “Maori standing place,” and the site of the murder was never exorcised, some of the kehua hid in the hold of the ocean liner taking Beverly out of New Zealand years later. They intended to ensure that the family did not lose its “spiritual habitation.”

All Saints’ Church by E. W. Pugin, located across the street from Beverley’s house, is a place where Alice has found solace.

Even the author feels the kehuas’ presence as she writes about Beverley and her family from her basement workroom: “At night there’s a general feeling of busyness around me, a sense of movement, an urgency, a stirring in air that’s never quite still…If I listen hard…[I hear] a sound I can interpret only as an intent breathing too close for comfort, and then a hissing and silence.” Walk-ins, Northern Kelpies, Livas’s sneaky demons, selkies, and the Welsh Cwn Annwn (the dogs of death) are also mentioned in this novel in which most of the characters (with the exception of Alice) are not Christian and are generally at loose ends spiritually. A Maori tells the author that “Ghost and spirits in many cultures..are used as metaphors for a hereditary dysfunction: curses last even unto the seventh generation.”

The action bounces around, and scenes in one part of the book may not be explained until much later in the book, when additional information is provided. Most readers, however, will be having so much fun with the details and the often hilarious dialogue that they will willingly set aside their questions and just follow Weldon’s lead wherever it takes them – through wicked stories of love and betrayal; often farcical scenes of sexual exhilaration; and satirical episodes about the trials of the mostly well-off as they search for meaning and purpose in political causes, jobs, and, in Scarlett’s case, designer clothing and accessories.

Each character tries to match his/her life to the perfect dwelling, a place which feels like the “home” everyone yearns for, and Weldon uses this a unifying motif throughout the novel. The author herself lives in Yatt house, an older house in Highcross, once belonging to the Bennett family, which sometimes “reappears,” with their dog. Beverley lives in Robinsdale, a Victorian Gothic house in the outer fringes of London; Scarlett (Beverley’s granddaughter) and her mate, Louis, live in Nopasaran, a 1930s modernist house designed by Wells Coates, in which the bedrooms are only alcoves, allowing no privacy at all; Cynara (Scarlett’s sister) lives in “a small, mean but practical terraced house” which she keeps because she wants to be “where the ‘real people’ are; and, living in Campion Towers, is Jackson Wright, handsome actor in Upstairs, Downstairs (for which Fay Weldon herself was honored with a Writers Guild Award for Best British TV Series). All these people are using their houses as extensions of themselves, perhaps looking for the kind of “belonging” which the kehua believe comes only when one joins with one’s extended family in the sacred and peaceful graveyard.

The buzzing the author hears around her computer turns out to be, not a kehua, but a hummingbird hawk moth.

Despite the novel’s impressionistic structure and lack of predictable chronology, the story moves quickly, at the same time that it also presents a vivid portrait of the author at work. Filled with ironies and understatements, and often hilarious in its dialogue, this novel has something to say about people and their need for connection to the past, at the same time that it can (and should) be read for the pure fun of its characters and point of view. A new addition to my Favorites list. Highly recommended to lovers of literary fiction.

ALSO by Fay Weldon: CHALCOT CRESCENT, BEFORE THE WAR

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk

The map of New Zealand is from http://www.freeworldmaps.net

The All Saints’ Church, by E. W. Pugin, described as being across the street from Beverley’s house is actually in Urmston. http://en.wikipedia.org Photo by Parrot of Doom/Tom Jeffs.

The Wells Coates house, depicted here, is found on http://benfleethistory.org.uk

The hummingbird hawk moth, which the author thought was a kehua when it buzzed around her computer screen appears on http://www.redbubble.com

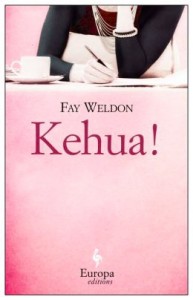

ARC: Europa Editions