“Don’t ever tell anybody about your bad dreams, people said. Tell your dreams to a hole in the ground and spit three times. They said similar things about good dreams. Don’t share them with anybody. Keep them to yourself. So, I wondered, were the only dreams you ever heard the dreams that were neither good nor bad?” –The boy, Dshurukuwaa.

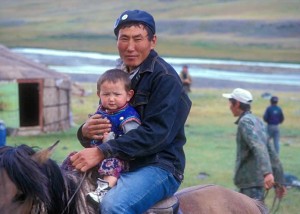

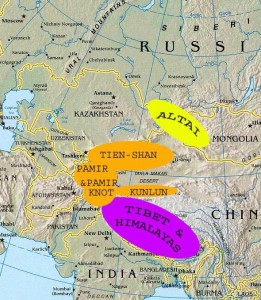

With a casual and natural curiosity about the mysteries of life, a young Tuvan boy from Mongolia muses about dreams in this quotation from The Blue Sky, clearly illustrating the aspects of this autobiographical novel which make it come alive so vibrantly for those of us who know nothing about his culture and are learning about it for the first time. Set in the 1940s, the novel recreates a time in which the old ways are the only ways for the Tuvan people, an isolated group of nomadic people living in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia on the Russian border. Using the point of view of Dshurukuwaa, the young Tuvan boy, the author tells a coming-of-age story which is clearly his personal story, as he observes the growth of the outside influences which are just beginning to affect his people. The boy is very much a little boy, always acting “in the minute,” reacting to daily events with all the passion of a child, and the author, Galsan Tschinag, is able to communicate the boy’s feelings to a foreign audience in ways which make the Tuvan culture both understandable and unforgettable.

With a casual and natural curiosity about the mysteries of life, a young Tuvan boy from Mongolia muses about dreams in this quotation from The Blue Sky, clearly illustrating the aspects of this autobiographical novel which make it come alive so vibrantly for those of us who know nothing about his culture and are learning about it for the first time. Set in the 1940s, the novel recreates a time in which the old ways are the only ways for the Tuvan people, an isolated group of nomadic people living in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia on the Russian border. Using the point of view of Dshurukuwaa, the young Tuvan boy, the author tells a coming-of-age story which is clearly his personal story, as he observes the growth of the outside influences which are just beginning to affect his people. The boy is very much a little boy, always acting “in the minute,” reacting to daily events with all the passion of a child, and the author, Galsan Tschinag, is able to communicate the boy’s feelings to a foreign audience in ways which make the Tuvan culture both understandable and unforgettable.

The author himself grew up in family of Tuvan herders – of sheep and sometimes yaks – living in collapsible yurts on the steppes and migrating to different locations as the family followed the seasons. His life, however, changed dramatically while he was still a child. The Russians occupied “his” lands, sending the author out of the steppes and into school, and later sending him to Leipzig, where he attended university and eventually received his doctorate. “I have been a gatherer, hunter, and herder; a school boy, a university student and a professor; a trade union journalist [and] a shadow politician…” the author says. Today, in his seventies, and back in Mongolia, he continues, “I am the chieftain of a tribe, a healer, an author [who writes in German], a father, and a grandfather,” and he can still slaughter and skin sheep, set up and take down a yurt, milk goats, and birth cows. The Blue Sky (2006, in English), the first of a trilogy about his life, is succeeded by The Gray Earth (2010) and The White Mountain, scheduled for publication later this year. Through this trilogy, the author shows the changes in the author’s life from the most traditional aspects of his closed culture in the 1940s to the connected world of the twenty-first century, in which, he says in an afterword, “With my shaman’s whisk, a truncheon, or a laptop [!], I alternate between living in the indigenous culture of the post-Socialist Tuvans…and the enlightened state monopoly of Western Europe.”

In his book, Dshurukuwaa, a young child, spends much time alone or with his dog Arsylang, since his father is always working with the family’s herd of sheep, and occasionally yaks; his mother is gathering food and doing domestic chores; and his older sister and brother, about whom we learn almost nothing, are away at a boarding school to which they were sent by a government official. Tied completely to nature and constantly moving with the seasons, the little boy and his family look for omens, and trust in Gok-Deeri, the god of the blue sky. His life changes dramatically with the arrival of his grandmother, “the warming sun at the beginning of my life” (to whom the author dedicates this book). An old woman with a shaved head, she is now alone, her husband having been killed by the Russians and her son killed by the Kazakhs. Her recent stay with her sister in another ail has not been benign: “Piece by piece, Grandma’s yurt and flock wandered into [her sister’s] possession.” She plans to reclaim her flock in the spring with the help of other family members so that she can give it to her grandson, to whom she now devotes the rest of her life.

When she leaves to get the flock, however, Dshurukuwaa has a terrible accident, for which his mother blames his grandmother, crying, “See?…It was the evil spirit that possessed your damn beasts and called for you!” Though both his parents suffer for his disaster and pain, and his mother greatly regrets her rash comments, the boy feels most sorry for his grandmother: “I will never fully grasp the agony Grandma had to bear. Only a person who has suffered as much as Grandma can understand how horrific, how immeasurable and ineffable her pain was.” The accident killed, for her, the “glimmer of hope that she might end her life among people who loved her, and that she might leave behind somebody on this earth who would remember her fondly and benefit from her efforts.”

The grandmother’s stories and their lessons, the activities of their daily lives, the occasional amusements, and folk wisdom regarding healing and health all emerge in this story about this hard-working family which is totally responsible for all its own needs. When Grandmother eventually becomes toothless, it is Dshurukuwaa who pre-chews her food for her, and when it is finally her time to leave the earth and “go home,” she tells her beloved grandson, enigmatically, “I will not get any older. Rather, I will grow younger, ever younger, and smaller, until I am a baby again. Once that has happened, I’ll hasten back to you.”

The contrasts between the boy’s family and the families of their relatives in other ails, whom they visit, show the unfortunate effects of outside influences – socialism, mandatory education, trade with the outside world, and the introduction of currency to business transactions, especially in transactions with the Russians, all of which change their  traditional ways of thinking and acting. Though his brother and sister return home to visit, bringing him his first taste of candy, the boy worries that they will have to leave again, and that “they will always have to leave again.” His sister, for the first time, is afraid of the jumping of his dog, his closest “friend,” and he begins to think about what will become of his herd, inherited from his grandmother, if he has to leave. A terrible winter, the worst in memory, forces the boy and his family to deal with disasters they could not have foreseen as the book comes to its close (to be continued in The Gray Earth). A stunning and important memoir, which memorializes a culture in the process of change.

traditional ways of thinking and acting. Though his brother and sister return home to visit, bringing him his first taste of candy, the boy worries that they will have to leave again, and that “they will always have to leave again.” His sister, for the first time, is afraid of the jumping of his dog, his closest “friend,” and he begins to think about what will become of his herd, inherited from his grandmother, if he has to leave. A terrible winter, the worst in memory, forces the boy and his family to deal with disasters they could not have foreseen as the book comes to its close (to be continued in The Gray Earth). A stunning and important memoir, which memorializes a culture in the process of change.

ALSO by Galsan Tschinag: THE GRAY EARTH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/

The Tuvan father and son on horseback are featured on http://mongolianaltai.uoregon.edu/

A yurt overlooking the Altai Mountains, originally uploaded by Adagio: http://en.wikipedia.org

A yak and sheep grazing in the late fall are from http://www.csmonitor.com/

The map of the Altai areas, bordering Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Russia, and China may be found on http://www.centralasiatravel.com/