Note: This novel was SHORTLISTED for the UK’s Orange Prize for 2012.

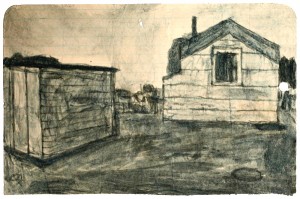

“When Tinu drew a room, he drew it empty. He drew it as it was but somehow what you saw was not the room but its emptiness. With a door you saw the opening. When he drew a pitchfork left leaning against the barn wall you saw its abandonment….If the rooms were real [however], the people were not. They were only symbols of people. They had no smiles.”

In this sensitive novel about an unusual and touching friendship, author Georgina Harding tells the story of life in a rural community in Romania beginning in the 1930s and extending through World War II and the Communist Occupation. As the novel opens, a sick and starving man has just arrived by train in Iasi, a place with which he is completely unfamiliar. He is looking for a woman, but he does not know where or how to find her. Knowing no one there, he spends the night on a park bench. In the morning he sees a nurse dressed in white walking past him, and, thinking she is an angel, he follows her to a hospital where he collapses at the entrance. The man is Augustin, known as Tinu, and he is looking for Safta, a childhood friend whom he has not seen since they were separated by the war and Communist Occupation.

In this sensitive novel about an unusual and touching friendship, author Georgina Harding tells the story of life in a rural community in Romania beginning in the 1930s and extending through World War II and the Communist Occupation. As the novel opens, a sick and starving man has just arrived by train in Iasi, a place with which he is completely unfamiliar. He is looking for a woman, but he does not know where or how to find her. Knowing no one there, he spends the night on a park bench. In the morning he sees a nurse dressed in white walking past him, and, thinking she is an angel, he follows her to a hospital where he collapses at the entrance. The man is Augustin, known as Tinu, and he is looking for Safta, a childhood friend whom he has not seen since they were separated by the war and Communist Occupation.

Years ago, they both lived at Poiana, a large country estate some distance from Iasi, the nearest city. The novel’s narrative moves back and forth in time, changing perspectives as the author alternates the action between Tinu and Safta during their years together at Poiana, and the present,  when they are adults in Iasu. Tinu, is the son of the estate’s cook, and Safta, the daughter of the estate’s owners, yet they form a unique and lasting bond. With exquisite care, the author recreates the world of childhood as Tinu and Safta experience and understand it, never resorting to easy sentimentality as she tells their stories.

when they are adults in Iasu. Tinu, is the son of the estate’s cook, and Safta, the daughter of the estate’s owners, yet they form a unique and lasting bond. With exquisite care, the author recreates the world of childhood as Tinu and Safta experience and understand it, never resorting to easy sentimentality as she tells their stories.

Tinu is both deaf and mute, and he is either uninterested or unable to learn sign language. He can write a few words, but does not seem able connect them with what they represent in the outside world. His only form of communication is through haunting drawings which he makes with soot and spit on found materials – paper, boxes, wrappings, pieces of cloth – and these drawings reflect an unusually selective view of the world. “Did he not care about people?” his mother wonders in his childhood. “He [makes] horses better  than humans…and cows and chickens.” Safta, with the innocence of childhood, sees how dramatically different his world is from her own, but she also understands intuitively the way he thinks and the conclusions he draws about life. From his infancy, he would “[watch] her dancing movements as if she was some flickering, endlessly absorbing film running before his eyes…the little girl a tiny dark silent actress,” not completely real. Though she tries to teach him to write, she is a child, too, easily distracted by the natural excitements of her own childhood, and she has other friends with whom to spend time, especially as she develops into adolescence and is courted by a summer visitor. “Tinu had a way that let you forget him,” she notes, years later. “Even when he stood right in front of you there was no insistence to his presence.”

than humans…and cows and chickens.” Safta, with the innocence of childhood, sees how dramatically different his world is from her own, but she also understands intuitively the way he thinks and the conclusions he draws about life. From his infancy, he would “[watch] her dancing movements as if she was some flickering, endlessly absorbing film running before his eyes…the little girl a tiny dark silent actress,” not completely real. Though she tries to teach him to write, she is a child, too, easily distracted by the natural excitements of her own childhood, and she has other friends with whom to spend time, especially as she develops into adolescence and is courted by a summer visitor. “Tinu had a way that let you forget him,” she notes, years later. “Even when he stood right in front of you there was no insistence to his presence.”

As the past unfolds, the simple, sensitively depicted scenes from childhood send out ripples that include the individual members of Safta’s family, the servants and Tinu’s family, visitors, villagers, and their children, and broaden naturally to encompass bigger, more complex observations about life and the novel’s themes of identity and connection. The author unifies the novel from beginning to end with perfect details, carefully connecting even the earliest scenes from the lives of Tinu and Safta with their perceptions as they grow, effectively shifting the focus back and forth between them at Poiana. She then puts everything into perspective through the later events in which Tinu is now a patient at the hospital where Safta works as a nurse. She has recognized Tinu at the hospital, and she brings him paper and drawing materials, “talking” to him daily, in hopes of unlocking and understanding the world into which he has retreated. Many scenes stir the reader’s emotions without being sentimental or maudlin, and the author’s respect for these characters (and her audience) is obvious.

Basic questions about how we know and understand each other, how we perceive the world, and how we communicate with it echo throughout the novel, and the outbreak of war and the eventual Occupation put these themes into stark perspective. As the adult Safta observes, “We’re all so many people, aren’t we, nowadays?…There are the people we are inside, then the people we used to be, then there are the people other people think we are.”

An intriguing story underlies the writing of this novel. According to Bloomsbury, Georgina Harding’s publisher, she had visited Romania years ago and had always wanted to contrast the horror of its modern history with the beauty of its landscape. To write as an “outsider,” however, is usually disastrous for a novelist who wants make characters and setting come alive. When Harding discovered by chance the artwork of American artist James Castle, a deaf mute from Garden Valley, Idaho, she realized that “his sooty drawings” on found materials resembled the scenes she remembered from Romania. By using Castle as the model for the main character here, the author was able to set the book in Romania, which she has visited but of which she is not a resident, and depict it through his eyes. Since he is self-isolated, this cancels the need of the author to tell about Romania from the “inside” and allows her to create a fascinating character-based novel of people in crisis.

1939 Lagonda

Though the novel is often breath-taking and profoundly moving, the elegant language sometimes gets in the way of natural-sounding dialogue. The character of Andrei, to whom Safta is drawn during her adolescent years, is thin, and the ending, though consistent in some ways with Tinu’s attitudes and limited ability to express feelings, is implausible. These seem like minor complaints about a superb book that I loved reading, however. Through this book, I have discovered a new (to me) author of startling, original talent, and second, through her, I have found the work of James Castle, the unusual “outsider artist” on whom she has based the character of Tinu. On my list of Favorites for 2012.

ALSO by Harding: THE GUN ROOM

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Murdo Macleod appears on http://www.guardian.co.uk

James Castle’s depiction of farm buildings may be found on http://www.brooklynrail.org/auction/james-castle The author based her depiction of Tinu on this American artist from Idaho (1899 – 1997). This drawing is on a piece of lined notebook paper.

James Castle’s free-standing people lack faces, as do Tinu’s. This photo appears on http://gapersblock.com/ac/2009/10/

Safta and her mother take Tinu to visit a monastery, and he is inspired by the colorful frescos and mosaics. The Putna Monastery may be seen on http://www.bestourism.com

Andrei, to whom Safta is drawn as a teenager, is remembered by Tinu primarily for his car, a Lagonda convertible, seen here:

http://www.conceptcarz.com

ARC: from Bloomsbury USA