Note: Gerald Murnane was WINNER of the Australia’s Patrick White Award in 1999, WINNER of the Australia Council Emeritus Award in 2008, and WINNER of the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction for this novel in 2018.

“I moved to this district near the border so that I could spend most of my time alone and so that I could live according to several rules that I had for long wanted to live by. I mentioned earlier that I ‘guard my eyes.’ I do this so that I might be more alert to what appears at the edges of my range of vision; so that I might notice at once any sight so much in need of my inspection that one or more of its details seems to quiver or to be agitated until I have the illusion that I am being signaled to or winked at.” Unnamed speaker of Border Districts

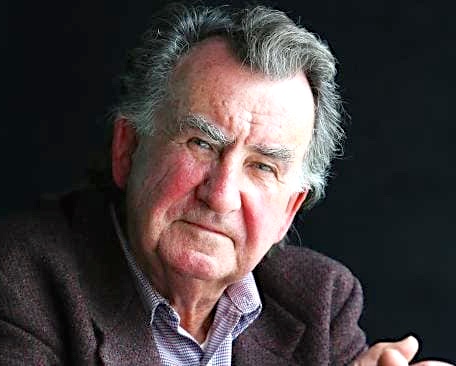

The speaker of this work of “fiction,” who appears in every way to be the author himself, insists that this book is, in fact, a report – “pages intended only for my files.” Despite this assertion, the resulting work is so introspective and so intimate, and the many known “facts” of the author’s own life are so clearly identical to events of the speaker’s life that the very borders between fact and fiction, reality and imagination, and observation and interpretation are blurred. The book feels like an internal monologue by a talented writer exploring the very nature of his own being, Its Australian author, Gerald Murnane, often suggested as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, appears to be so invested in the nature of thought and its creative manifestation through writing that he is willing to sacrifice what many of us would regard as everything physical that has had meaning for him in the past to find answers to his inner questions. The book which has resulted is unlike anything else I have ever read – a book without a plot, without a real conflict, and without a clear sense of direction – yet I found it hypnotizing.

The speaker of this work of “fiction,” who appears in every way to be the author himself, insists that this book is, in fact, a report – “pages intended only for my files.” Despite this assertion, the resulting work is so introspective and so intimate, and the many known “facts” of the author’s own life are so clearly identical to events of the speaker’s life that the very borders between fact and fiction, reality and imagination, and observation and interpretation are blurred. The book feels like an internal monologue by a talented writer exploring the very nature of his own being, Its Australian author, Gerald Murnane, often suggested as a candidate for the Nobel Prize, appears to be so invested in the nature of thought and its creative manifestation through writing that he is willing to sacrifice what many of us would regard as everything physical that has had meaning for him in the past to find answers to his inner questions. The book which has resulted is unlike anything else I have ever read – a book without a plot, without a real conflict, and without a clear sense of direction – yet I found it hypnotizing.

The decision of the book’s speaker to give up everything familiar in his life and move to a tiny, unnamed town near the border between two rural districts, also unnamed but presumably in western Australia, parallels the decision made not long ago by Gerald Murnane himself, the intensity of his own need for a similar change reflected in a decision which would be anathema to every book collector I have ever known. The speaker, like Murnane, tells us early in the book that in moving to the plains to be alone, he gave up his entire library. He failed, he says “as a reader of fiction because I was constantly engaged not with the seeming subject-matter of the text but with the doings of personages who appeared to me while I tried to read and with the scenery that appeared around them. My image-world was sometimes only slightly connected with the text in front of my eyes.” Later, he further explains that “I certainly recall some of what took place in my mind while I read; I can recall many images that occurred to me and many moods that overcame me, but the words and sentences that were in front of my eyes when the images occurred or the moods arose – of those countless items I recall hardly any.” Why keep the books, then, he must have asked himself, as he prepared to change and simplify his whole life.

The decision of the book’s speaker to give up everything familiar in his life and move to a tiny, unnamed town near the border between two rural districts, also unnamed but presumably in western Australia, parallels the decision made not long ago by Gerald Murnane himself, the intensity of his own need for a similar change reflected in a decision which would be anathema to every book collector I have ever known. The speaker, like Murnane, tells us early in the book that in moving to the plains to be alone, he gave up his entire library. He failed, he says “as a reader of fiction because I was constantly engaged not with the seeming subject-matter of the text but with the doings of personages who appeared to me while I tried to read and with the scenery that appeared around them. My image-world was sometimes only slightly connected with the text in front of my eyes.” Later, he further explains that “I certainly recall some of what took place in my mind while I read; I can recall many images that occurred to me and many moods that overcame me, but the words and sentences that were in front of my eyes when the images occurred or the moods arose – of those countless items I recall hardly any.” Why keep the books, then, he must have asked himself, as he prepared to change and simplify his whole life.

The speaker has seen in his peripheral vision the image of leaves and vines in the stained glass window in a tiny nearby church, but he refuses to look at it directly, “guarding his eyes” against intrusive images until it “calls” to him.

Murnane himself has stated in interviews that this will be his last book, one of many absolute statements he has made in interviews in his effort to put his life into perspective. Certainly the speaker’s adoption of an almost hermit-like lifestyle suggest that his efforts will also be his last. He states, for example, that going forward, he intends to “guard his eyes,” as he has said in the quotation which begins this review, perhaps a result of his early upbringing and his schooling by religious brothers who encouraged their students to visit the chapel whenever, during the day, they felt stressed. The speaker, like the author, admits that he used to take advantage of this emotional outlet. He also mentions that there is a tiny Protestant church near where he lives now, closed and deserted during the day, a place with a small stained glass window at the front entrance. He chooses, however, not to look closely at it, “guarding his eyes” so that the magic of new perceptions may unfold at the periphery if it is worth his attention. He admits that he has never traveled more than a day’s journey by road or rail from where he lives, and that foreign cities exist as mental images. When he travels, the speaker is determinedly avoids all signposts, route numbers, and directions for reaching places that are out of view. He has never used a computer or other electronic device. He needs to live in the moment, without distraction from “border districts.”

The speaker, like author Murnane himself, is a fan of horse racing, and especially enjoys seeing the racing silks.

Soon he begins what appears to be an interior monologue, starting with one image, then reminiscing or imagining and moving on to another, and then another. In the course of the book he repeats images in new contexts (stained glass and changing light, horse racing and the color of its silks, beautiful glass marbles, a kaleidoscope and its changing images, religious institutions, and the wide plains where he lives), using these to involve the reader in the search for what gives meaning to this author’s life. Characters repeat, as do episodes from childhood, expanding each time, with one experience at a wedding reception occurring more than once as he imagines people over time, even imagining the life of an elderly woman there who might have been in love once, whose love might also have died at Gallipoli during World War I, and who might have had a child. The life of the spirit, including, at one point, the Holy Spirit, and the effects of time on memory are examined, always within the context of some aspect of the speaker’s life, and he experiments successfully with meditation as a way of further expanding his mental images.

The novel, or report, as the author prefers it to be called, feels much like poetry, in places, with images crowding in upon each other so closely that they encourage readers to conjure up similar images or experiences of their own, thereby participating in the memories and thoughts of the writer while expanding their own. Since there is no traditional plot, conflict, or sense of direction, except inside the borders of the speaker’s own mind, readers who share that journey with similar journeys inside their own minds will be accomplishing the author’s overall goal, expanding their own borders through their participation and their own memories. It is a daring – perhaps unique – goal, one which I found thrilling as I began to see Murnane’s imagery, especially of stained glass, in new ways and see some parallels to my own life. It is difficult to know what to call this book, if one cares to categorize it, because it reaches depths of “personhood” – the author’s and the internal “personhoods” of the readers he has touched – something very different from that of regular fiction and non-fiction. Ultimately, the most appropriate conclusion to this review may be to quote Murnane’s own conclusion, which, itself, is a quotation of the thoughts of Percy Bysshe Shelley:

“Life like a dome of many-colored glass

Stains the radiance of Eternity.”

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.theaustralian.com.au/

The speaker has seen, in his peripheral vision, the image of leaves and vines in the stained glass window in a tiny nearby church, but he refuses to look at it directly, “guarding his eyes” against an intrusive images until it “calls” to him. https://www.topsimages.com/

The speaker, like author Murnane himself, is a fan of horse racing, and especially enjoys seeing the racing silks. https://www.pinterest.com/

The light shining through glass marbles is another image that repeats throughout the novel. This collection of vintage glass marbles is seen on https://www.etsy.com/