“A bear of a man – tough as salt pork and bred to survive hardship. While others wilted and died…Adams remained in rude health. He munched his way through joints of raw penguin to keep himself alive [on the journey to Japan] and, when he had sucked the bones until the marrow ran dry, he gnawed the salt-toughened leather that surrounded the mast ropes.”

Born among poor fisherfolk in Gillingham in Kent in 1564, William Adams’s family moves to Limehouse, a Thameside district of wharves and shipyards, when he is twelve, so it is not surprising that he himself eventually seeks his own future on the sea, despite its hardships and the less than encouraging survival rate for crews that sign on for long trips. Reports touting the riches of China, Africa, India, the Spice Islands, South America, and other exotic and far-off lands have been arriving in England regularly, inspiring trading companies and adventurers to seek their fortunes by mapping new sea routes to new countries, and, in the process, establishing new trading posts, acquiring new markets for their goods, and bringing new goods and wealth back to England. England’s enemies, the Spanish and Portuguese, are also seeking routes to the same lands and markets, however, compounding the dangers of the sea, for which there is only limited knowledge of navigation, with the dangers spawned by greed – being captured by the Spanish or Portuguese – a certain death sentence. Ship captains have always been able to obtain crewmen for dangerous and risky journeys into the unknown, however, a fact that probably says as much about living conditions for the poor in England as it does about any desire for adventure.

Born among poor fisherfolk in Gillingham in Kent in 1564, William Adams’s family moves to Limehouse, a Thameside district of wharves and shipyards, when he is twelve, so it is not surprising that he himself eventually seeks his own future on the sea, despite its hardships and the less than encouraging survival rate for crews that sign on for long trips. Reports touting the riches of China, Africa, India, the Spice Islands, South America, and other exotic and far-off lands have been arriving in England regularly, inspiring trading companies and adventurers to seek their fortunes by mapping new sea routes to new countries, and, in the process, establishing new trading posts, acquiring new markets for their goods, and bringing new goods and wealth back to England. England’s enemies, the Spanish and Portuguese, are also seeking routes to the same lands and markets, however, compounding the dangers of the sea, for which there is only limited knowledge of navigation, with the dangers spawned by greed – being captured by the Spanish or Portuguese – a certain death sentence. Ship captains have always been able to obtain crewmen for dangerous and risky journeys into the unknown, however, a fact that probably says as much about living conditions for the poor in England as it does about any desire for adventure.

When William Adams is seventeen, Sir Francis Drake sails up the Thames, returning in triumph as the first Englishman to sail around the world. Not incidentally, he arrives with a huge booty for Queen Elizabeth. The largest, most elaborate celebration since the reign of King Henry VIII, takes place aboard The Golden Hind at its anchorage in Deptford, on the Thames, easily visible to all on shore, and the Queen herself comes aboard. Few young men like William Adams, contemplating life on the sea and perhaps standing shoreside, are able to resist the lure of such excitement.

After an apprenticeship as a shipwright, Adams takes to the sea at age 23, commanding a supply ship carrying food and ammunition to the English fleet as it battles the Spanish Armada, and, later, trading on the Barbary Coast. When he eventually hears rumors that a Dutch company is seeking pilots for a fleet of five ships going to the Spice Islands in the East Indies, he signs on, bringing his brother, too. Though the risks are high, “the potential rewards are enormous. The ship sets out on a route around South America in order to avoid the Spanish and Portuguese in and around Africa. At the end of nineteen catastrophic months, the now 36-year-old Adams and twenty-four desperately ill and dying crew members arrive in April, 1600, at the south end of Japan, the first Englishmen ever to do so.

After an apprenticeship as a shipwright, Adams takes to the sea at age 23, commanding a supply ship carrying food and ammunition to the English fleet as it battles the Spanish Armada, and, later, trading on the Barbary Coast. When he eventually hears rumors that a Dutch company is seeking pilots for a fleet of five ships going to the Spice Islands in the East Indies, he signs on, bringing his brother, too. Though the risks are high, “the potential rewards are enormous. The ship sets out on a route around South America in order to avoid the Spanish and Portuguese in and around Africa. At the end of nineteen catastrophic months, the now 36-year-old Adams and twenty-four desperately ill and dying crew members arrive in April, 1600, at the south end of Japan, the first Englishmen ever to do so.

Adams’s experiences in Japan and his association with its rulers serve as the framework of Giles Milton’s book, a biography which also chronicles the opening of this hitherto unknown country to western trade. Because the author provides detailed and lively descriptions of London life and society in the late 1500’s at the beginning of this book, the reader can easily visualize how greatly English “civilization” contrasts with the superior Japanese culture which Adams discovers upon his arrival, and which the author describes in detail. As an early Portuguese visitor notes, “Apart from our religion, we are greatly inferior to them.” Adams quickly learns the Japanese language and adopts Japanese customs and dress, always treating his hosts with respect and honor. Eventually, Adams becomes ruler Ieyasu’s interpreter, even in dealings with the duplicitous Portuguese. Stranded in Japan with no hope of escape, Adams “becomes Japanese,” finding the rude and riotous behavior of the Portuguese and eventually the Dutch as offensive as do his hosts.

Samurai Willia m is an extremely readable, scholarly study of the opening (and in 1637, the closing) of Japan to western trade. Using many primary sources, Milton creates an exciting story of how Japan comes to be “discovered,” what its values and culture are, and why the intrusion of the west and the possibility of trade are eventually rebuffed. The contrasts Milton sets up throughout the biography attest to his appreciation of 17th century Japanese society. Though he clearly does not agree with the sense of quick justice, the immediate executions, and the brutality and torture carried out by the Japanese in the name of justice, he shows his admiration for their courage and sense of honor, their loyalty and respect for authority, their beautifully constructed and aesthetically pleasing gardens in Kyoto, the grandeur of the palace in Edo (now the Imperial Palace in Tokyo), along with more mundane characteristics, such as their concern for hygiene and bathing, their medical practices (including acupuncture), their care for their appearance and cleanliness, their careful food preparation with its emphasis on freshness and healthiness, and their quiet self-control. The obvious contrasts to the mores of western society show how the hierarchical, non-individualized focus of the Japanese led to a more community-oriented society with a much higher level of “civilization” than that of the adventurer-traders, who were out for personal benefits, no matter the costs to their host country.

m is an extremely readable, scholarly study of the opening (and in 1637, the closing) of Japan to western trade. Using many primary sources, Milton creates an exciting story of how Japan comes to be “discovered,” what its values and culture are, and why the intrusion of the west and the possibility of trade are eventually rebuffed. The contrasts Milton sets up throughout the biography attest to his appreciation of 17th century Japanese society. Though he clearly does not agree with the sense of quick justice, the immediate executions, and the brutality and torture carried out by the Japanese in the name of justice, he shows his admiration for their courage and sense of honor, their loyalty and respect for authority, their beautifully constructed and aesthetically pleasing gardens in Kyoto, the grandeur of the palace in Edo (now the Imperial Palace in Tokyo), along with more mundane characteristics, such as their concern for hygiene and bathing, their medical practices (including acupuncture), their care for their appearance and cleanliness, their careful food preparation with its emphasis on freshness and healthiness, and their quiet self-control. The obvious contrasts to the mores of western society show how the hierarchical, non-individualized focus of the Japanese led to a more community-oriented society with a much higher level of “civilization” than that of the adventurer-traders, who were out for personal benefits, no matter the costs to their host country.

Though Samurai William Adams is the real-life role  model for James Clavell’s Shogun, I found him far more true to life and interesting in this book. Neither romanticized nor idealized, he exists here as a man with flaws, often speaking in his own voice. His life as a seaman and his life in Japan, are fascinatingly portrayed, attesting both to Milton’s scholarship and his imagination as he recreates successfully the two cultural and social milieux in which Adams spent his two very different lives.

model for James Clavell’s Shogun, I found him far more true to life and interesting in this book. Neither romanticized nor idealized, he exists here as a man with flaws, often speaking in his own voice. His life as a seaman and his life in Japan, are fascinatingly portrayed, attesting both to Milton’s scholarship and his imagination as he recreates successfully the two cultural and social milieux in which Adams spent his two very different lives.

Photos, in order: The author ‘s photo appears on http://www.festivalnews.uts.edu.au

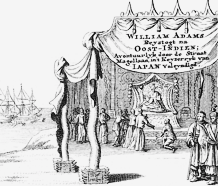

All the remaining photos appear on the Wiki page for William Adams (sailor): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Adams_(sailor)

*A stylized portrait of William Adams

*William Adams being presented to Tokugawa Ieyasu, in an idealized depiction from 1707.

*One of the two Japanese suits of armor presented by the Tokugawa for King James I in 1613, now in the Tower of London.

*The grave of William Adams (Miura Anjin), in Hirado, Kyushu, Japan