Note: In 1996 author Graham Swift was WINNER of the Booker Prize and WINNER of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Last Orders. He was also WINNER of the Guardian Fiction Prize for Waterland in 1983.

“It was a strange business, this Mothering Sunday ahead of them, a ritual already fading, yet the Nivens – and the Sheringhams – still clung to it, as the world itself, or the world in dreamy Berkshire, still clung to it, for the same sad, wishing-the-past-back reasons. As the Nivens and the Sheringhams perhaps clung to each other more than they’d used to, as if they’d become one common decimated family.”

As the novel opens on March 30, 1924, the Nivens, Sheringhams, and others throughout England are celebrating Mothering Sunday, a holiday in which the citizens, aristocracy and servants alike, celebrate their mothers. Servants are especially happy, as they all get a day off to travel to their homes and visit with family. Jane Fairchild, who works as a housemaid at Beechwood in an atmosphere much like that of a small Downton Abbey, will not be traveling, however. A foundling deposited at the door of an orphanage shortly after she was born, Jane has never known a mother or a father, does not know any birth name she may have had, and has spent her whole life in an orphanage – until, at age fourteen, she entered “service.” At sixteen she begins working for the Niven family, which, in the aftermath of World War I, has reduced the number of their household servants to two – Milly, the cook, and Jane, the maid.

As the novel opens on March 30, 1924, the Nivens, Sheringhams, and others throughout England are celebrating Mothering Sunday, a holiday in which the citizens, aristocracy and servants alike, celebrate their mothers. Servants are especially happy, as they all get a day off to travel to their homes and visit with family. Jane Fairchild, who works as a housemaid at Beechwood in an atmosphere much like that of a small Downton Abbey, will not be traveling, however. A foundling deposited at the door of an orphanage shortly after she was born, Jane has never known a mother or a father, does not know any birth name she may have had, and has spent her whole life in an orphanage – until, at age fourteen, she entered “service.” At sixteen she begins working for the Niven family, which, in the aftermath of World War I, has reduced the number of their household servants to two – Milly, the cook, and Jane, the maid.

As we learn in the opening pages, Jane, now twenty-two, has been having a secret sexual relationship for the past six years with the only surviving son and heir of neighboring aristocrats. On the holiday, that young man, Paul Sheringham, will be entertaining Jane in his own house and in his own bed for the first time, and, at his request, Jane will arrive at the estate’s front door as an equal, not at the servants’ entrance. Paul’s parents and the Nivens are off visiting with their friends, the Hobdays, celebrating Paul’s future marriage to Emma Hobday, a woman of “appropriate” class. The wedding is scheduled to be held in just two weeks.

Mr. Nevin takes his wife in the Humber car as they meet the Sheringhams and Hobdays at an inn for lunch.

Author Graham Swift sets the tone and mood at the outset with the inclusion of a one-sentence epigraph introducing the novella: “You shall go to the ball.” And while his audience may be thinking of Cinderella and happy endings, Swift also introduces the opening paragraph with “Once upon a time, before the boys were killed, when there were more horses than cars, and before the male servants disappeared…” The dark ironies involving the shattering loss of four young sons of the Niven and Sheringham families during the war, along with the developing new world order and the changing values of their society at all levels indicate a far more complex story than the happy-ending stories of childhood. As Jane shares her seemingly circumscribed life within which she gradually shows signs of intellectual growth, and Paul tries to survive his differently circumscribed life with some sense of integrity and independence, the reader becomes aware of just how much society has changed with the world war and how much these changes affect the future of the entire nation. The whole notion of personal freedom and independence for all, not just the aristocracy, is challenging the very foundations of social life.

Jane leaves Beechwood on “the second bicycle” to meet Paul Sheringham at Upleigh when the Nevins depart for the inn. She is pleased to arrive, not by a back road but by cycling directly to the front entrance and entering as an equal.

Though Paul Sheringham was supposed to join his family, friends, and future wife, Emma Hobday, for a late lunch during the holiday, he has chosen to entertain Jane instead, telling the others that he has to study for some law exams, though “he had as much intention of becoming a lawyer as becoming a lettuce.” His assignation with Jane, passionate and sexual, brings a sense of peace to Jane, who understands what is at stake and knows that this will probably be their last time together, and even as she watches Paul get up from the bed, she believes that “There never was a day like this nor ever will be or can be again.” As for Paul, “he wanted her to be there, [though] it might have been her role in another life, in a commoner comic story, to be already scurrying downstairs, still adjusting her clothing. It was his wish before he left, to see here there, to have her there, nakedly and…immovably occupying his bedroom, so that the image of her would be there, branding itself on his mind, even as he met…his [bride-to-be].” He delays and delays his departure, eventually leaving the house so late that his absence will certainly embarrass his family, friends, and future in-laws, and especially his fiancee, awaiting his arrival at the inn.

About halfway through the book, Swift unexpectedly changes the time frame. Jane is now in her nineties, and, as she describes changes in her life over the past sixty-five years, she also provides more information about her early life at the Nivens’ estate, showing the reader how some elements of her early life, especially regarding her interest in adventure books, play out more fully over the course of her adult life. An acute observer of the people around her, she is now living a happy and productive old age, fulfilled in ways which she and the reader never expected when she was in her twenties. It is to Swift’s credit that the reader is able to understand how Jane arrived at her goals though the author has presented this information casually and without much emphasis during the early action of the book, requiring the reader to form conclusions on his/her own. Jane’s long interest in reading, which Mr. Niven encouraged by allowing her to borrow books from his library, allows her to make sense of her new experiences and to feel a new kind of independence. Though she seems to trace everything in her life back to her last day with Paul Sheringham, she regards that time as almost holy, and has never shared that story with anyone else, except the reader.

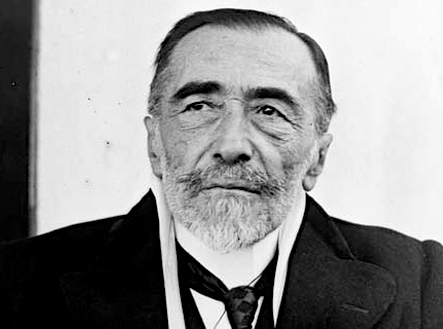

After her assignation with Paul Sheringham, Jane returns by bike to Beechwood, where she begins reading Joseph Conrad’s YOUTH, eventually reading most of Conrad’s work in the aftermath of unfolding events.

Swift never spells out Jane’s inner quandaries leading up to her arrival at “the ball” during the seventy years between opening and closing of the novel. Instead, the reader follows Jane obliquely as the author provides information which Jane has previously kept private, leaving it up to the reader to fill in the blanks between what she says in her old age and any issues which must have arisen as she matured. The reader, always on her side, shares in her life, despite her reticence, and the novel speeds along on the strength of its characters’ independent decisions and their life-changing moments, however small they may seem to the world at large. Times change, but those who can find a “language” for expressing what they have to say have a chance at getting at the truth, “the very feel of being alive.”

ALSO by Swift: WISH YOU WERE HERE, HERE WE ARE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.enviedecrire.com

The 1924 Humber leaving the front of an elegant house might have been the car that Mr. Nevin drove to his meeting with the Sheringhams and the Hobdays.

The photo of the young woman on the bicycle is part of the collection at http://www.oldbike.eu/museum/

Paul is scheduled to meet Emma at the Swan Inn on the Thames at 1:30 but leaves Upleigh at an embarrassingly late time. Photo by Richard Leigh. https://www.tripadvisor.com

After Jane returns to Beechwood, she reads a book from Mr. Nevin’s library , YOUTH by Joseph Conrad, the first of many Conrad books Jane later reads with excitement. As Conrad was still alive until August, 1924, Jane even fantasizes about having an encounter with Conrad. http://www.famousauthors.org/joseph-conrad