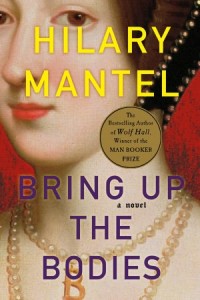

Note: This book is WINNER of the Man Booker Prize for 2012 and WINNER of the Costa Award for 2012.

“The order goes to the Tower, ‘Bring up the bodies.’ Deliver, that is, the accused men…to Westminster Hall for trial…It is 12 May [1536], a Friday. They are brought in by armed guards through a fulminating crowd shouting the odds [on whether] they live or die…The [crowd] does not understand the law…There is only one penalty for high treason: for a man, to be hanged, cut down alive and eviscerated, or for a woman, to be burned.”

In her previous novel, Wolf Hall, author Hilary Mantel, recreates the dramatic story of Sir Thomas More’s trial and execution in July, 1535, during the reign of King Henry VIII. As she opens this novel, a continuation of that story, set just three months later, More’s downfall is still fresh in the minds of everyone at Henry’s court. Thomas Cromwell, who prosecuted More on behalf of the king, is now Henry’s chief minister, firmly ensconced in the power structure of the Tudor Court. He will have plenty of work to do over the next seven or eight months. Katherine of Aragon, Henry’s queen of twenty years, is now living in her own court with her daughter Mary, her marriage to Henry having been annulled in 1533, while Henry was living with Anne Boleyn. Henry is now married to Anne, a calculating but beautiful woman who has never been shy about using her wiles to get what she wants, but he has now wearied of her. Though

In her previous novel, Wolf Hall, author Hilary Mantel, recreates the dramatic story of Sir Thomas More’s trial and execution in July, 1535, during the reign of King Henry VIII. As she opens this novel, a continuation of that story, set just three months later, More’s downfall is still fresh in the minds of everyone at Henry’s court. Thomas Cromwell, who prosecuted More on behalf of the king, is now Henry’s chief minister, firmly ensconced in the power structure of the Tudor Court. He will have plenty of work to do over the next seven or eight months. Katherine of Aragon, Henry’s queen of twenty years, is now living in her own court with her daughter Mary, her marriage to Henry having been annulled in 1533, while Henry was living with Anne Boleyn. Henry is now married to Anne, a calculating but beautiful woman who has never been shy about using her wiles to get what she wants, but he has now wearied of her. Though  Anne has given birth to Elizabeth, she has been unable to bear him a son, and with the marriage less exciting than it once was, Henry has convinced himself that she never will bear him the heir he wants. Assigning Cromwell to find a way to free him from his new queen, Henry begins to pursue the plain and modest Jane Seymour, whose virginal ways stand in sharp contrast to those of Anne.

Anne has given birth to Elizabeth, she has been unable to bear him a son, and with the marriage less exciting than it once was, Henry has convinced himself that she never will bear him the heir he wants. Assigning Cromwell to find a way to free him from his new queen, Henry begins to pursue the plain and modest Jane Seymour, whose virginal ways stand in sharp contrast to those of Anne.

The personal, political, and religious conflicts among the families and courtiers of Katherine, who is Catholic; the ambitious family and friends of Anne Boleyn, who, are, of necessity, a part of the Church of England; and eventually the family of Jane Seymour create myriad complications for Henry and his ministers, especially Thomas Cromwell. Everyone at court must take care that the internecine rivalries remain in check, and Cromwell, especially, must constantly watch his back.

Young Henry VIII

As complex as Henry’s personal life may be, his political relationships with France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire are also perpetually changing. War is always threatening, none of the countries trust each other, and secret negotiations regarding marriages of state, the exchange of envoys, and the creation of secret alliances are always under way. The annulment of Henry’s marriage to Katherine, done over the objections of the papacy, and the “certification” of his new marriage to Anne Boleyn have led to a complete break with the papacy. Henry is now the head of his own Church of England, though his theology remains virtually unchanged, and he, Cromwell, and the priests in England are constantly wrangling about the practical issues of their church vs. the papacy. Of particular importance is Henry’s decision to seize monasteries, starting with the smaller ones, with all the assets and lands going to Henry to pay for his court and his wars.

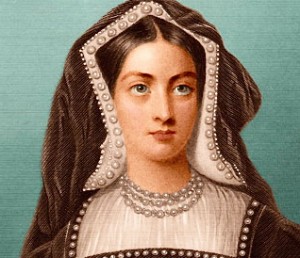

Katherine of Aragon

Author Hilary Mantel focuses the novel on Cromwell, who must deal with the members of all the various factions of the court and all the international intrigue. An error could be fatal to him. She vividly recreates the complex maneuvering on all levels as Henry becomes impatient to be freed of Anne. As Cromwell comes up with a plan which will satisfy Henry, the characters and the period come vibrantly to life, despite the intricacies of genealogy and the political complexity. The devious plot to entrap Anne and those who support her (since her family and her courtiers can never be trusted to simply change their allegiances to Henry once she is out of favor) unfolds with a kind of panache and care for realistic details that are rarely seen in fiction – a scheme so clever and full of malice that it sometimes feels like a secret memoir from the period.

Queen Anne Boleyn

From the initial interrogation of one of Anne’s terrified ladies-in-waiting, who is willing to say what Cromwell wants to hear in exchange for the cancellation of her embarrassing debts, to the insinuation of Anne’s crimes by numerous other (jealous) ladies-in-waiting who simply dislike her, Cromwell develops a case against Anne. As the characters talk at cross purposes, the clever dialogue becomes filled with dramatic irony. When questioned, several lords who have been lured into the web, have no choice but to say what they are expected to say – either with or without torture, guilty or innocent. As Thomas Wriothesley, “Call-Me-Risley,” an officer of state, remarks to Cromwell while they are discussing the list of those who will go on trial, “I see [now]. It is not so much, who is guilty, as whose guilt is of service to you. I admire you, sir. You are deft in these matters, and without false compunction.”

Jane Seymour

The lively dialogue in these strong dramatic scenes conveys information as well as the characters’ feelings. At the same time, it also inspires feelings within the reader – anger, sympathy, resentment, or even pity for these characters, all of whom are pawns. Cromwell’s questioning of people reveals their fright, their resentment of Cromwell, their jealousy of Anne, or their attraction to Anne. The degree to which the women, especially, are the lowliest pawns of all in the great game of court politics is obvious, and the extent to which other courtiers are limited in their choice of actions becomes especially clear as the grand plot against Anne Boleyn is revealed.

The Tower of London

As the action moves inexorably to the novel’s climax with arrests, trials, and gruesome executions, the reader understands just how all this came about, marveling at Mantel’s ability to make the reader feel not only like a witness to history but like a participant in it. When Anne ultimately faces trial, the reader that all this horror has happened in the mere seven months (and four hundred pages) since the novel opened. Though I am not generally a fan of historical fiction from this period, I have become a huge fan of Hilary Mantel, her writing so effective on so grand a scale that it is difficult to imagine how any other novel could surpass this one for the major literary prizes of the year.

Note: In her Author’s Note at the end of the book, Mantel describes Cromwell as “sleek, plump, and densely inaccessible, like a choice plum in a Christmas pie; but I hope to continue my efforts to dig him out,” good news for Mantel’s fans who are hoping for a continuation of Cromwell’s story.

ALSO by Hilary Mantel, WOLF HALL and THE ASSASSINATION OF MARGARET THATCHER

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on

http://www.bbc.co.uk

Henry VIII, Portrait by Joos van Cleve, from http://tudorhistory.org

Katherine of Aragon, photo from Getty Images: http://www.guardian.co.uk

Queen Anne Boleyn: from http://www.fanpop.com

Jane Seymour: from http://www.anne-boleyn.com

The Tower of London: from http://www.copyright-free-pictures.org.uk