Note: Hiromi Kawakami was WINNER of the Tanizaki Prize, Japan’s highest literary prize, in 2001, for her novel called, in English, The Briefcase. She was also the WINNER of the Akutagawa Prize for the best literary story published that year.

“I don’t dislike Mr. Nakano, I thought to myself. There are plenty of people in the world I don’t dislike, some of whom I almost like; on the other hand, I almost hate some of those whom I don’t dislike, too. But how many people did I truly love? I wondered, as I clasped Takeo’s hand lightly.”—Hitomi Suganuma, main speaker.

Author Hiromi Kawakami, for all her prizes and prize nominations, also wins hearts and creates smiles with her off-beat and surprising novels. With an ability to create characters who are sometimes so ordinary that they become interesting, she puts her characters into new situations in which they, with their limited personal and emotional resources, live their lives in full sight of us all. Unpretentious and casual, her main character here, Hitomi Suganuma works as a cashier at the Nakano Thrift Shop, where she sometimes has only half a dozen customers a day. She has plenty of time to observe those around her, to think about their lives, and to contemplate her own future. Fun and funny, the novel that results is almost as unfocused as Hitomi is, lying halfway between a novel and a collection of interrelated short stories, and it all works. The character portraits are unforgettable as author Kawakami brings them to life in ways that will surprise those readers who think of the Japanese as formal and reserved. The characters here are unafraid to say what they think, to be sexy and uninhibited while remaining polite, and to be independent in their lifestyles.

Author Hiromi Kawakami, for all her prizes and prize nominations, also wins hearts and creates smiles with her off-beat and surprising novels. With an ability to create characters who are sometimes so ordinary that they become interesting, she puts her characters into new situations in which they, with their limited personal and emotional resources, live their lives in full sight of us all. Unpretentious and casual, her main character here, Hitomi Suganuma works as a cashier at the Nakano Thrift Shop, where she sometimes has only half a dozen customers a day. She has plenty of time to observe those around her, to think about their lives, and to contemplate her own future. Fun and funny, the novel that results is almost as unfocused as Hitomi is, lying halfway between a novel and a collection of interrelated short stories, and it all works. The character portraits are unforgettable as author Kawakami brings them to life in ways that will surprise those readers who think of the Japanese as formal and reserved. The characters here are unafraid to say what they think, to be sexy and uninhibited while remaining polite, and to be independent in their lifestyles.

Main character Hitomi Suganuma is in her mid-twenties, a woman alienated from her mother, with whom she has little to no contact, and, having broken up with the only boyfriend she ever had, her personal goal now is to find someone new. The only candidate at the thrift shop is Takeo, who acts as a pickup and delivery person, hauling merchandise around for Mr. Nakano. Bullied in school, years ago, Takeo is missing part of his little finger, the result of a bully slamming his finger in an iron door, something which concerned Mr. Nakano initially, since “finger shortening” is a practice of the yakuza, the Japanese mob, which is involved in the sale of used goods, primarily antiques. When Takeo dropped out of school six months from graduation, his parents paid little attention, preferring to believe that this was a lifestyle choice and a result of his lack of discipline. Now working at Mr Nakano’s shop, Takeo considers Hitomi to be “complex” because she likes books. Mr. Nakano, in his fifties, has been in business for about twenty-five years. He has had three marriages and has three children, including a six-month-old baby, yet he appears to have a girlfriend on the side, a conclusion Takeo has made based on the number of unexplained trips he makes to “the bank.”

Main character Hitomi Suganuma is in her mid-twenties, a woman alienated from her mother, with whom she has little to no contact, and, having broken up with the only boyfriend she ever had, her personal goal now is to find someone new. The only candidate at the thrift shop is Takeo, who acts as a pickup and delivery person, hauling merchandise around for Mr. Nakano. Bullied in school, years ago, Takeo is missing part of his little finger, the result of a bully slamming his finger in an iron door, something which concerned Mr. Nakano initially, since “finger shortening” is a practice of the yakuza, the Japanese mob, which is involved in the sale of used goods, primarily antiques. When Takeo dropped out of school six months from graduation, his parents paid little attention, preferring to believe that this was a lifestyle choice and a result of his lack of discipline. Now working at Mr Nakano’s shop, Takeo considers Hitomi to be “complex” because she likes books. Mr. Nakano, in his fifties, has been in business for about twenty-five years. He has had three marriages and has three children, including a six-month-old baby, yet he appears to have a girlfriend on the side, a conclusion Takeo has made based on the number of unexplained trips he makes to “the bank.”

These three spend much time together at the thrift shop, often eating meals and drinking beer together, near or after closing time, and they form a sort of loose family. Hitomi has no social life, Takeo has broken with his girlfriend and has no after-work life, and Mr. Nakano is happy to have a reason to stay away from his own home and spend more time at “the bank.” They take care of each other, and when an older man, Tadokoro, starts spending time inside the shop when Hitomi is alone there, and then wants her to buy some erotic photos, Mr. Nakano takes action. Mr. Nakano’s sister Masayo, in her mid-fifties, is also often present, though she disappears at length when she is tending to her lover, a situation which Hitomi finds fascinating and about which she sometimes asks personal questions of Masayo regarding sex. She uses a bonus she receives from Masayo to take Takeo out drinking with her.

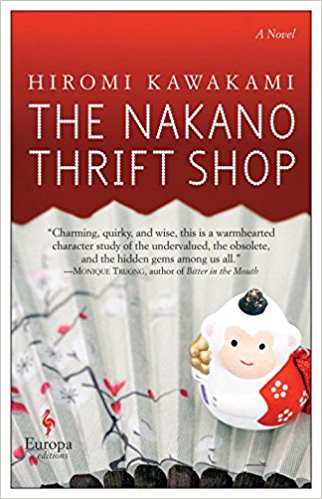

A Japanese nodding figure, a hundred years old. Note that there is a small piece of metal that goes through the neck and rests on the shoulders of the figure to allow it to nod when the head is touched.

With these simple characters and their obvious personality quirks and curiosities, author Kawakami builds her story, and she has no qualms about having her characters casually raise the most personal questions about sex, impotence, love-making, love hotels, and betrayals of love. Her characters will say anything. As the novel evolves and becomes more complex through scenes that could also be short stories, for which the author has also won prizes, the author has ample opportunity to move around in time and place without having to have much in the way of transitional scenes to connect one chapter with another. The overall story of long-term relationships moves forward with plenty of complications and flashbacks and flashforwards. Guiding all the action are individual tales of love and rejection and the strong characterizations of Mr. Nakano, Hitomi, Takeo, Masayo, and assorted minor characters.

The Goryeo celadon bowl from Korea (918 – 1392) was far more valuable than what Mr. Nakano sold in his shop, creating a more complicated situation when one arrived at the shop, unexpectedly.

Ultimately, time catches up with the Nakano Thrift Shop, and Mr. Nakano begins to participate in on-line auctions and sales. Questions arise as to what he might be planning for the business and what that would mean for the employees. The author solves the mysteries for the reader by writing a last chapter that takes place two years ahead in time, showing the future. A delight to read at the same time that it raises questions about relationships, personalities, and the roles of strong women, the novel works because the author defies conventions by creating characters who are so ordinary – universal, even – that they could represent any of us in their desires for happiness and satisfaction. There are no big plot twists here, just as there are usually few of those in our real lives, and a grand finale would be out of place in a book about such people leading conventional lives. Like the thrift shop itself, with its myriad little objects “found in a typical household from the 1960s and later,” none of which are of great value, the experiences which the characters here share with us are little events, which become important for their cumulative, not individual, importance in the characters’ lives. Ultimately, the reader sees how much like the world of the thrift shop real life is, “a strange world, in which whatever was new and neat and tidy diminished in value,” while messy real life is what matters.

ALSO by Hiromi Kawakami, reviewed here: Tanizaki Prize WINNER, THE BRIEFCASE and THE TEN LOVES OF NISHINO

Photos, in order: The author’s picture is from http://rereadinglives.blogspot.com/

The Japanese nodding figure is from a personal snapshot.

The Daruma doll, common in Japanese thrift shops, may be found on https://www.goodsfromjapan.com

Korean celadon from the Goryeo dynasty (918 – 1392) is too valuable to appear at a thrift shop. This one is from the Museum of Oriental Ceramics in Osaka, Japan. https://www.pinterest.com